“You dropped a hundred and fifty grand on a f***** education you coulda' got for a dollar fifty in late charges at the public library.” —Good Will Hunting

I was a user of computational chemistry for years, but one with relatively little understanding of how things actually worked below the input-file level. As I became more interested in computation in graduate school, I realized that I needed to understand everything much more deeply if I hoped to do interesting or original work in this space. From about August 2021 to December 2023, I tried to learn as much about how computational chemistry worked as I could, with the ultimate goal of being able to recreate my entire computational stack from scratch.

I found this task pretty challenging. Non-scientists don’t appreciate just how esoteric and inaccessible scientific knowledge can be: Wikipedia is laughably bad for most areas of chemistry, and most scientific knowledge isn’t listed on Google at all but trapped in bits and pieces behind journal paywalls. My goal in this post is to describe my journey and index some of the most relevant information I’ve found, in the hopes that anyone else hoping to learn about these topics has an easier time than I did.

This post is a directory, not a tutorial. I’m not the right person to explain quantum chemistry from scratch. Many wiser folks than I have already written good explanations, and my hope is simply to make it easier for people to find the “key references” in a given area. This post also reflects my own biases; it’s focused on molecular density-functional theory and neglects post-Hartree–Fock methods, most semiempirical methods, and periodic systems. If this upsets you, consider creating a companion post that fills the lacunæ—I would love to read it!

I started my journey to understand computational chemistry with roughly three years of practice using computational chemistry. This meant that I already knew how to use various programs (Gaussian, ORCA, xTB, etc), I was actively using these tools in research projects, and I had a vague sense of how everything worked from reading a few textbooks and papers. If you don’t have any exposure to computational chemistry at all—if the acronyms “B3LYP”, “def2-TZVPP”, or “CCSD(T)” mean nothing to you—then this post probably won’t make very much sense.

Fortunately, it’s not too hard to acquire the requisite context. For an introduction to quantum chemistry, a good resource is Chris Cramer's video series from his class at UMN. This is pretty basic but covers the main stuff; it's common for one of the classes in the physical chemistry sequence to also cover some of these topics. If you prefer books, Cramer and Jensen have textbooks that go slightly more in depth.

For further reading:

In general, computational chemistry is a fast-moving field relative to most branches of chemistry, so textbooks will be much less valuable than e.g. organic chemistry. There are lots of good review articles like this one which you can use to keep up-to-date with what's actually happening in the field recently, and reading the literature never goes out of style.

All of the above discuss how to learn the theory behind calculations—to actually get experience running some of these, I'd suggest trying to reproduce a reaction that you've seen modeled in the literature. Eugene Kwan's notes are solid (if Harvard-specific), and there are lots of free open-source programs that you can run like Psi4, PySCF, and xTB. (If you want to use Rowan, we've got a variety of tutorials too.) It's usually easiest to learn to do something by trying to solve a specific problem that you're interested in—I started out trying to model the effect of different ligands on the barrier to Pd-catalyzed C–F reductive elimination, which was tough but rewarding.

Molecular dynamics is important but won’t be covered further here. The best scientific introduction to MD I've come across is these notes from M. Scott Shell. If you want to go deeper, I really liked Frenkel/Smit; any knowledge of statistical mechanics will be very useful too, although I don’t have any recommendations for stat-mech textbooks. To get started actually running MD, I'd suggest looking into the OpenFF/OpenMM ecosystem, which is free, open-source, and moderately well-documented by scientific standards. (I've posted some intro scripts here.)

Cheminformatics is a somewhat vaguely defined field, basically just "data science for chemistry," and it's both important and not super well documented. If you're interested in these topics, I recommend just reading Pat Walters' blog or Greg Landrum's blog: these are probably the two best cheminformatics resources.

As with all things computational, it's also worth taking time to build up a knowledge of computer science and programming—knowing how to code is an investment which will almost always pay itself back, no matter the field. That doesn't really fit into this guide, but being good at Python/Numpy/data science/scripting is worth pursuing in parallel, if you don't already have these skills.

I started my computational journey by trying to write my own quantum chemistry code from scratch. My disposition is closer to “tinkerer” than “theorist,” so I found it helpful to start tinkering with algorithms as quickly as possible to give myself context for the papers I was trying to read. There are several toy implementations of Hartree–Fock theory out there that are easy enough to read and reimplement yourself:

Based on these programs, I wrote my own Numpy-based implementation of Hartree–Fock theory, and got it to match values from the NIST CCCBDB database.

iteration 05: ∆P 0.000001 E_elec -4.201085 ∆E -0.000000 SCF done (5 iterations): -2.83122 Hartree orbital energies: [-2.30637605 -0.03929435] orbital matrix: [[-0.71874445 0.86025802] [-0.44259188 -1.02992712]] density matrix: [[1.03318718 0.63622091] [0.63622091 0.39177514]] Mulliken charges: [[1.32070648 0.81327091] [1.10313469 0.67929352]]

I highly recommend this exercise: it makes quantum chemistry much less mysterious, but also illustrates just how slow things can be when done naïvely. For instance, my first program took 49 minutes just to compute the HF/6-31G(d) energy of water, while most quantum chemistry codes can perform that calculation in under a second. Trying to understand this discrepancy was a powerful motivation to keep reading papers and learning new concepts.

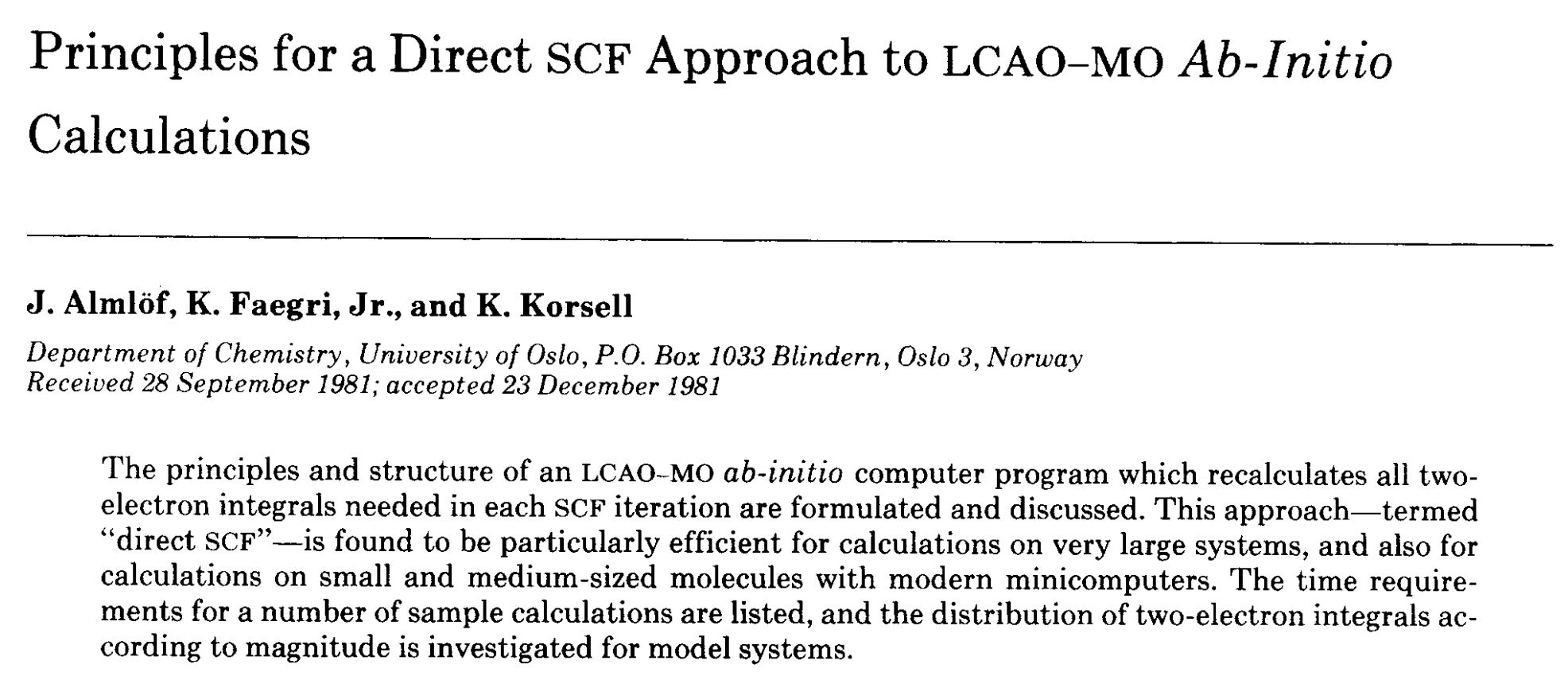

Armed with a basic understanding of what goes into running a calculation, I next tried to understand how “real” computational chemists structure their software. The best single paper on this topic, in my opinion, is the “direct SCF” Almlof/Faegri/Korsell paper from 1982. It outlines the basic method by which almost all calculations are run today, and it’s pretty easy to read. (See also this 1989 followup by Haser and Ahlrichs, and this 2000 retrospective by Head-Gordon.)

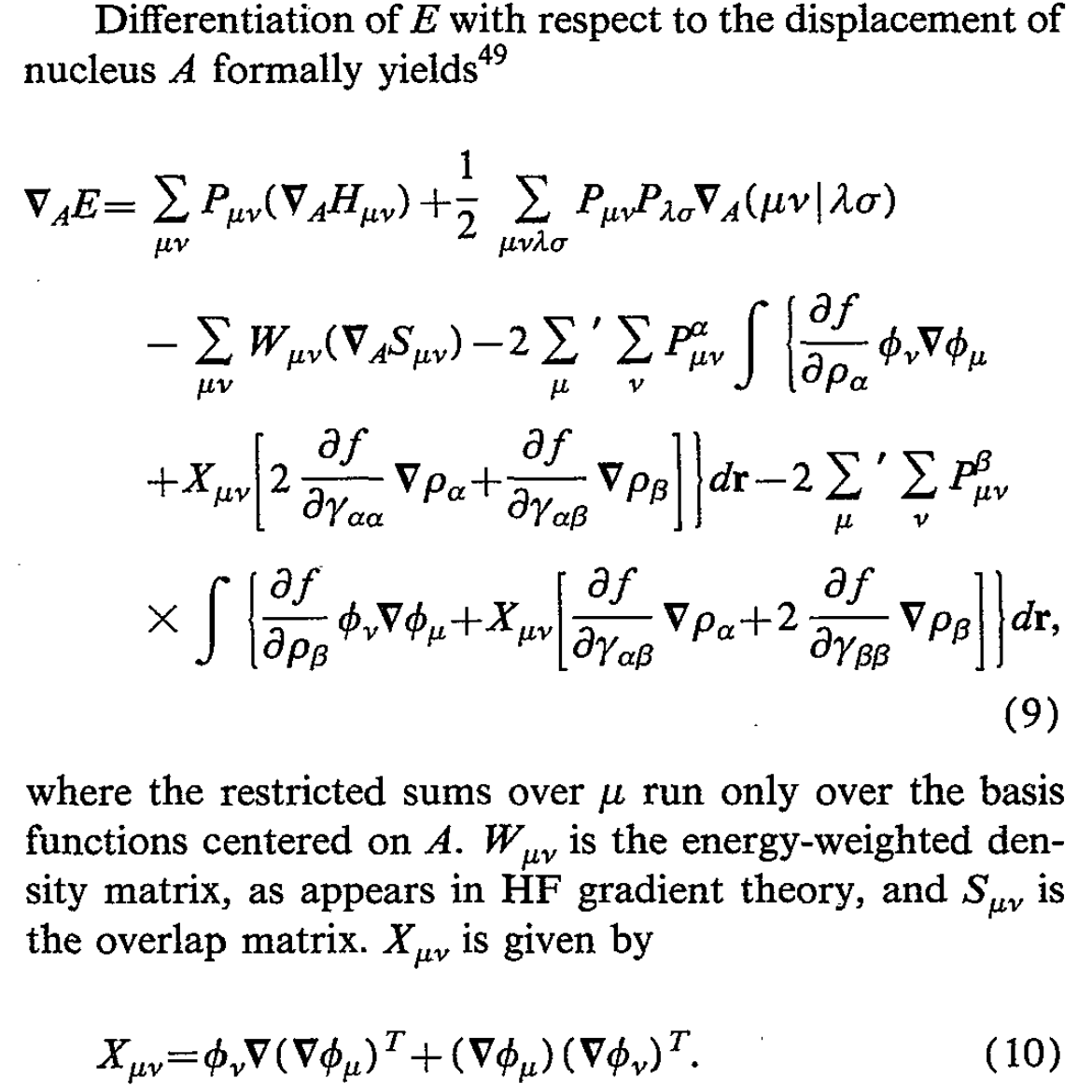

I found several other papers very useful for building high-level intuition. This overview of self-consistent field theory by Peter Gill is very nice, and Pople’s 1979 paper on analytical first and second derivatives within Hartree–Fock theory is a must-read. This 1995 Pulay review is also very good.

Using the intuition in these papers, I was able to outline and build a simple object-oriented Hartree–Fock program in Python. My code (which I called hfpy, in allusion to the reagent) was horribly inefficient, but it was clean and had the structure of a real quantum chemistry program (unlike the toy Jupyter Notebooks above). Here’s some of the code that builds the Fock matrix, for instance:

for classname in quartet_classes.keys():

num_in_class = len(quartet_classes[classname])

current_idx = 0

while current_idx < num_in_class:

batch = ShellQuartetBatch(quartet_classes[classname][current_idx:current_idx+Nbatch])

# compute ERI

# returns a matrix of shape A.Nbasis x B.Nbasis x C.Nbasis x D.Nbasis x NBatch

ERIabcd = eri_MMD(batch)

shell_quartets_computed += batch.size

for i, ABCD in enumerate(batch.quartets):

G = apply_ERI(G, *ABCD.indices, bf_idxs, ERIabcd[:,:,:,:,i], ABCD.degeneracy(), dP)

current_idx += Nbatch

# symmetrize final matrix

# otherwise you mess up, because we've added (10|00) and not (01|00) (e.g.)

G = (G + G.T) / 2

if incremental:

molecule.F += G

else:

molecule.F = molecule.Hcore + G

print(f"{shell_quartets_computed}/{shell_quartets_possible} shell quartets computed")

Any quantum-chemistry developer will cringe at the thought of passing 5-dimensional ERI arrays around in Python—but from a pedagogical perspective, it’s a good strategy.

Armed with a decent roadmap of what I would need to build a decent quantum chemistry program, I next tried to understand each component in depth. These topics are organized roughly in the order I studied them, but they’re loosely coupled and can probably be addressed in any order.

As I read about various algorithms, I implemented them in my code to see what the performance impact would be. (By this time, I had rewritten everything in C++, which made things significantly faster.) Here’s a snapshot of what my life looked like back then:

benzene / 6-31G(d)

12.05.22 - 574.1 s - SHARK algorithm implemented

12.20.22 - 507.7 s - misc optimization

12.21.22 - 376.5 s - downward recursion for [0](m)

12.22.22 - 335.9 s - Taylor series approx. for Boys function

12.23.22 - 300.7 s - move matrix construction out of inner loops

12.25.22 - 267.4 s - refactor electron transfer relation a bit

12.26.22 - 200.7 s - create electron transfer engine, add some references

12.27.22 - 107.9 s - cache electron transfer engine creation, shared_ptr for shell pairs

12.28.22 - 71.8 s - better memory management, refactor REngine

12.29.22 - 67.6 s - more memory tweaks

01.03.23 - 65.1 s - misc minor changes

01.05.23 - 56.6 s - create PrimitivePair object

01.07.23 - 54.7 s - Clementi-style s-shell pruning

01.08.23 - 51.7 s - reduce unnecessary basis set work upon startup

01.10.23 - 49.9 s - change convergence criteria

01.11.23 - 61.1 s - stricter criteria, dynamic integral cutoffs, periodic Fock rebuilds

01.12.23 - 42.5 s - improved DIIS amidst refactoring

01.20.23 - 44.7 s - implement SAD guess, poorly

01.23.23 - 42.6 s - Ochsenfeld's CSAM integral screening

01.30.23 - 41.7 s - improve adjoined basis set generally

02.08.23 - 38.2 s - introduce spherical coordinates. energy a little changed, to -230.689906932 Eh.

02.09.23 - 12.3 s - save ERI values in memory. refactor maxDensityMatrix.

02.15.23 - 9.0 s - rational function approx. for Boys function

02.18.23 - 8.7 s - minor memory changes, don't recreate working matrices in SharkEngine each time

Here's a rough list of the topics I studied, with the references that I found to be most helpful in each area.

Writing your own QM code illustrates (in grisly fashion) just how expensive computing electron–electron repulsion integrals (ERIs) can be. This problem dominated the field’s attention for a long time. In the memorable words of Jun Zhang:

Two electron repulsion integral. It is quantum chemists’ nightmare and has haunted in quantum chemistry since its birth.

To get started, Edward Valeev has written a good overview of the theory behind ERI computation. For a broad overview of lots of different ERI-related ideas, my favorite papers are these two accounts by Peter Gill and Frank Neese. (I’ve probably read parts of Gill’s review almost a hundred times.)

Here are some other good ERI-related papers, in rough chronological order:

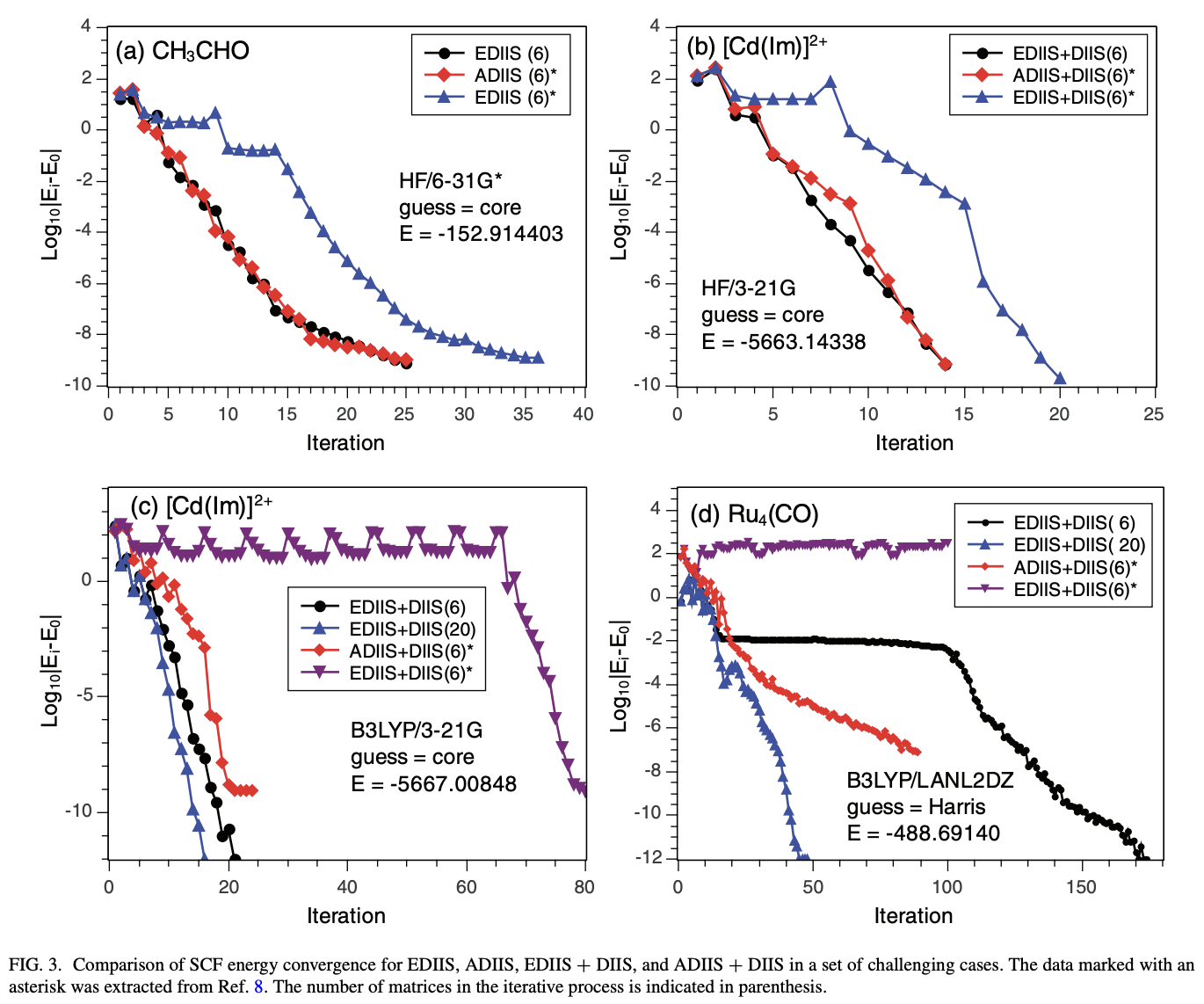

Writing your own QM code also illustrates how important SCF convergence can be. With the most naïve approaches, even 15–20 atom molecules often struggle to converge—and managing SCF convergence is still relatively unsolved in lots of areas of chemistry today, like radicals or transition metals.

This is obviously a big topic, but here are a few useful references:

Density-fitting/resolution-of-the-identity (“RI”) approaches are becoming de rigueur for most applications. This 1995 Ahlrichs paper explains “RI-J”, or density fitting used to construct the J matrix (this 1993 paper is also highly relevant.) This 2002 Weigend paper extends RI-based methods to K-matrix construction. Sherrill’s notes are useful here, as is the Psi4Numpy tutorial.

RI methods require the use of auxiliary basis sets, which can be cumbersome to deal with. This 2016 paper describes automatic auxiliary basis set generation, and this 2023 paper proposes some improvements. There’s now a way to automatically create auxiliary basis sets through the Basis Set Exchange API.

For Hartree–Fock theory, there are a lot of nice example programs (linked above); for density-functional theory, there are fewer examples. Here are a few resources which I found to be useful:

For large systems, it’s possible to find pretty large speedups and reach a linear-scaling regime for DFT (excepting operations like matrix diagonalization, which are usually pretty fast anyway). This 1994 paper discusses extending the fast multipole method to Gaussian distributions, and how this can lead to linear-scaling J-matrix construction, and this 1996 paper discusses a similar approach. This other 1996 paper describes a related near-linear-scaling approach for K matrices. There are a bunch more papers on various approaches to linear scaling (Barnes–Hut, CFMM, GvfMM, Turbomole’s RI/CFMM, etc), but I think there are diminishing marginal returns in reading all of them.

Geometry optimization for molecular systems is pretty complicated. Here’s a sampling of different papers, with the caveat that this doesn’t come close to covering everything:

I think the best guides here are the Gaussian vibrational analysis white paper and the Gaussian thermochemistry white paper—they basically walk through everything that’s needed to understand and implement these topics. It’s now pretty well-known that small vibrational frequencies can lead to thermochemistry errors; Rowan has a blog post that discusses this and similar errors.

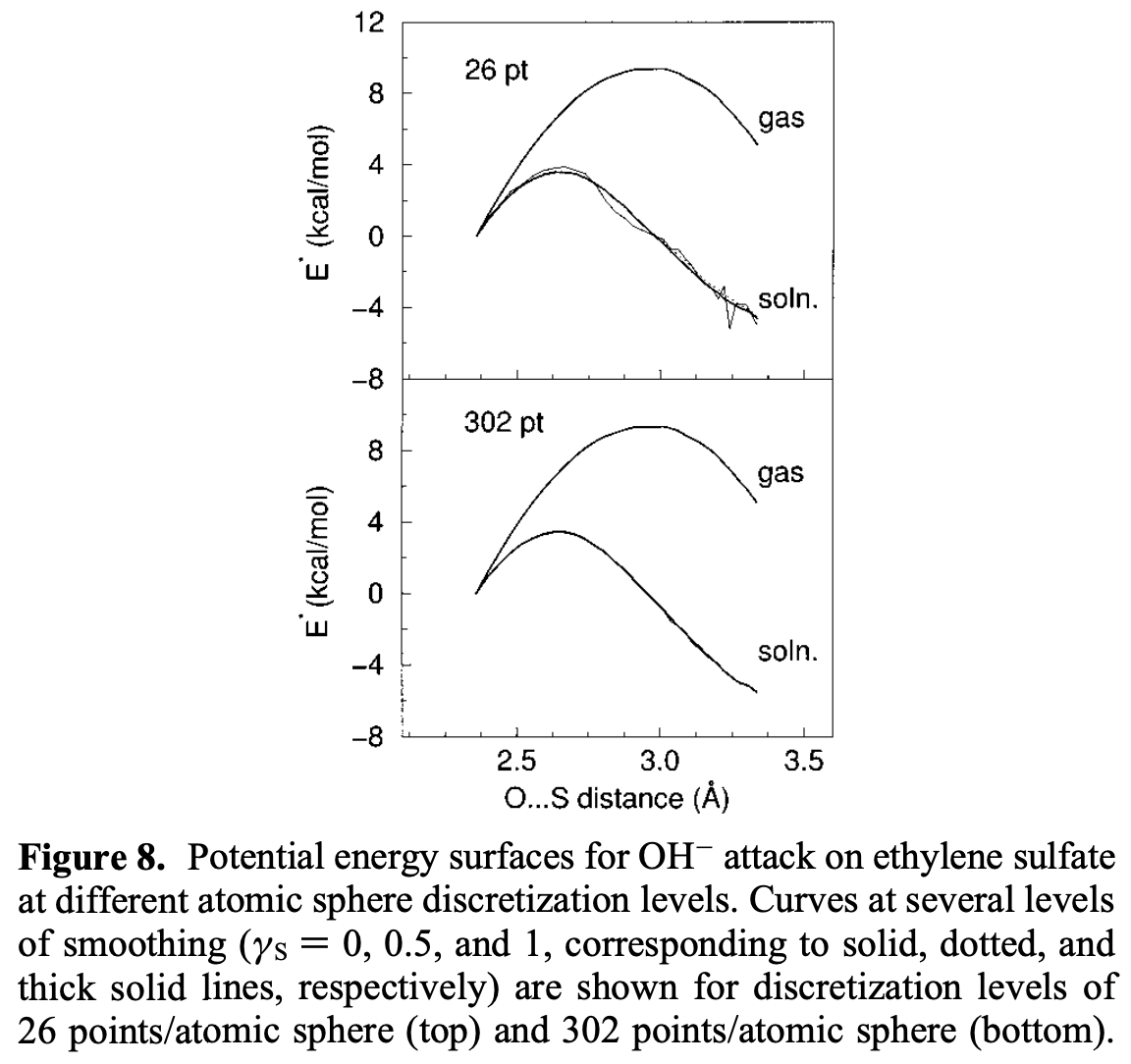

Implicit solvent models, while flawed, are still essential for a lot of applications. This 1993 paper describes the COSMO solvation method, upon which most modern implicit solvent methods are built. Karplus and York found a better way to formulate these methods in 1999, which makes the potential-energy surface much less jagged:

While there are many more papers that one could read in this field, these are the two that I found to be most insightful.

I haven’t talked much about basis sets specifically, since most basis-set considerations are interwoven with the ERI discussion above. But a few topics warrant special mention:

There are hundreds of other papers which could be cited on these topics, to say nothing of the myriad topics I haven’t even mentioned here, but I think there’s diminishing marginal utility in additional links. The knowledge contained in the above papers, plus ancillary other resources, were enough to let me write my own quantum-chemistry code. Over the course of learning all this content, I wrote four different QM programs, the last of which, “Kestrel,” ended up powering Rowan for the first few months after we launched.

These programs are no longer directly relevant to anything we do at Rowan. We retired Kestrel last summer, and now exclusively use external quantum-chemistry software to power our users’ calculations (although I’ve retained some strong opinions; we explicitly override Psi4’s defaults to use the Stratmann–Scuseria–Frisch quadrature scheme, for instance).

But the years I spent working on this project were, I think, an important component of my scientific journey. Rene Girard says that true innovation requires a “mastery” of the past’s achievements. While I’m far from mastering quantum chemistry, I think that I’d be ill-suited to understand the impact of recent advances in neural network potentials without having immersed myself in DFT and conventional physics-based simulation for a few years.

And, on a more personal note, learning all this material was deeply intellectually satisfying and a fantastic use of a few years. I hope this post conveys some of that joy and can be helpful for anyone who wants to embark on a similar adventure. If this guide helped you and you have thoughts on how I could make this better, please feel free to reach out!

Thanks to Peter Gill, Todd Martínez, Jonathon Vandezande, Troy Van Voorhis, Joonho Lee, and Ari Wagen for helpful discussions.