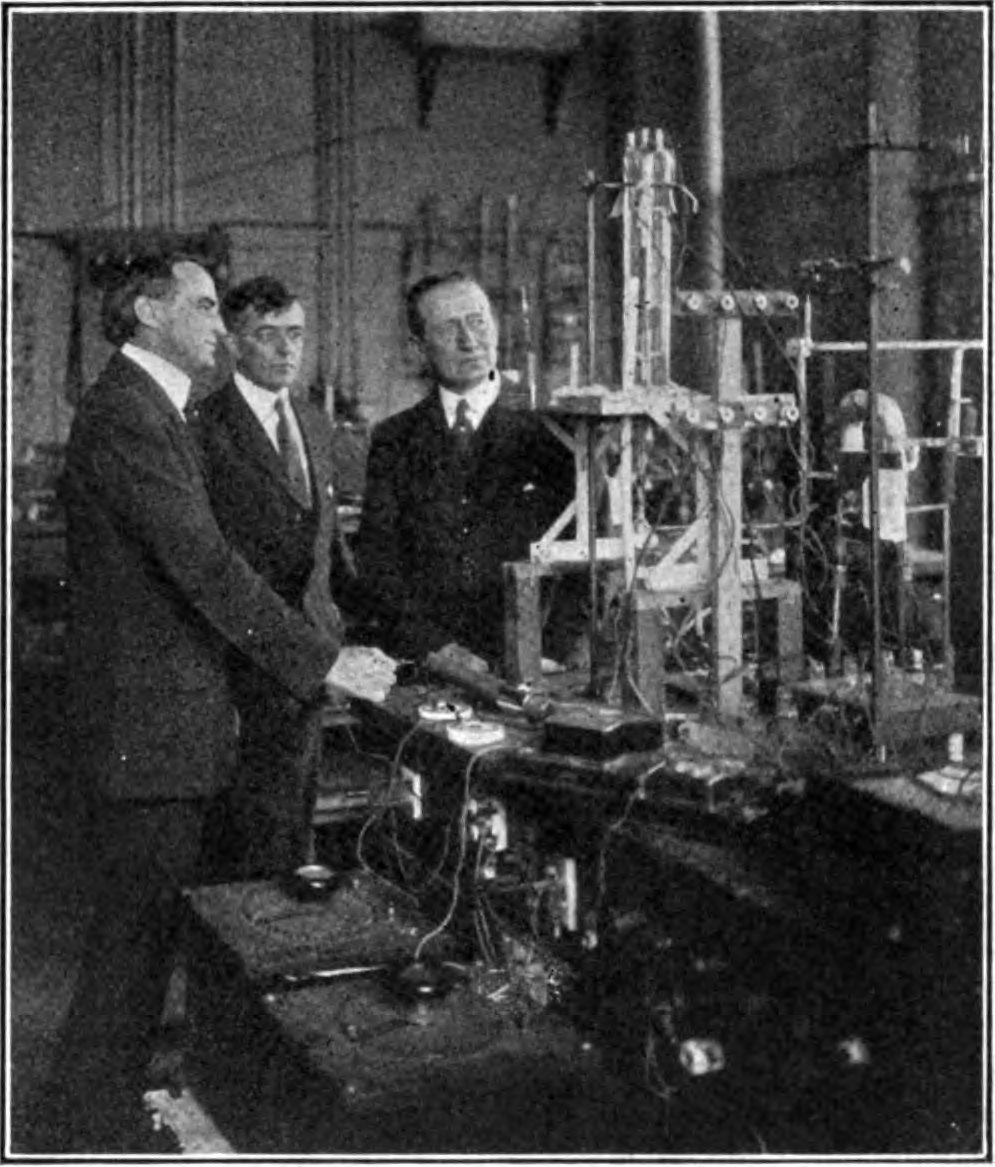

Eric Gilliam, whose work on the history of MIT I highlighted before, has a nice piece looking at Irving Langmuir’s time at the General Electric Research Laboratory and how applied science can lead to advances in basic research.

Gilliam recounts how Langmuir started working on a question of incredible economic significance to GE—how to make lightbulbs last longer without burning out—and after embarking on a years-long study of high-temperature metals under vacuum, not only managed to solve the lightbulb problem (by adding an inert gas to decrease evaporation and coiling the filament to prevent heat loss), but also starting working on the problems he would later become famous for studying. In Langmuir’s own words:

The work with tungsten filaments and gases done prior to 1915 [at the GE laboratory] had led me to recognize the importance of single layers of atoms on the surface of tungsten filaments in determining the properties of these filaments.

Indeed, Langmuir was awarded the 1932 Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for his discoveries and investigations in surface chemistry.”

Nor were lightbulbs the only thing Langmuir studied at GE: he invented a greatly improved form of vacuum pump, invented a hydrogen welding process used to construct vacuum-tight seals, and employed thin films of molecules on water to determine accurate molecular sizes with unprecedented accuracy. Gilliam argues that this tremendous productivity can in part be attributed to the fact that Langmuir’s work was in constant contact with practical problems, which served as a source of scientific inspiration:

In a developed world that is not exactly beset by scarcity and hardship anymore, it is hard to come up with the best areas to explore out of thin air. Pain points are not often obvious. Fundamental researchers can benefit massively from going to a lab mostly dedicated to making practical improvements to things like light bulbs and pumps and observing/asking questions. It is, frankly, odd that we normalized a system in which so many of our fundamental STEM researchers are allowed to grow so disjoint from the applied aspects of their field in the first place.

And Langmuir himself seems to agree:

As [the GE] laboratory developed it was soon recognized that it was not practicable nor desirable that such a laboratory should be engaged wholly in fundamental scientific research. It was found that at least 75 per cent of the laboratory must be devoted to the development of the practical applications. It is stimulating to the men engaged in fundamental science to be in contact with those primarily interested in the practical applications.

Let’s bring in our second thinker. Last weekend, I had the privilege of attending a lecture by Johnathan Bi on Rene Girard and the philosophy of innovation, which discussed (among other things) how a desire for “disruption” above all else actually makes innovation more difficult. To quote Girard’s “Innovation and Repetition,” which Bi discussed at length:

The main prerequisite for real innovation is a minimal respect for the past and the mastery of its achievements, i.e., mimesis. To expect novelty to cleanse itself of imitation is to expect a plant to grow with its roots up in the air. In the long run, the obligation always to rebel may be more destructive of novelty than the obligation never to rebel.

What does this mean? Girard is describing two ways in which innovation can fail. The first is quite intuitive—if we hew to tradition too much, if we have an excessive respect for the past and not a “minimal respect,” we’ll be afraid to innovate. This is the oft-derided state of stagnation.

The second way in which we can fail to innovate, however, is a bit more subtle. Girard is saying that innovation also requires a mastery of the past’s achievements; we can’t simply ignore tradition, we have to understand what exists before we can innovate on top of it. Otherwise we will be, in Girard’s words, like a plant “with its roots up in the air.” All innovation has to occur within its proper context—to quote Tyler Cowen, “context is that which is scarce.”

This might seem a little silly. Innovation, “the introduction of new things, ideas or ways of doing something” (Oxford), at first inspection seems not to depend on tradition at all. But novelty with no hope of improvement over the status quo is simply a cry for attention; wearing one’s shoes on the wrong feet may be unusual, but is unlikely to win one renown as a great innovator.

What does this mean for scientific innovation, and how does this connect to Gilliam’s thoughts about Langmuir and the GE Research Laboratory? I’d argue that much of our fundamental research today, even that which is novel, lacks the context necessary to be transformatively innovative. Often the most impactful discoveries aren’t those which self-consciously aim to be Science or Nature papers, but those which simply aim to address outstanding problems or investigate anomalies. For instance, our own lab’s interest in hydrogen-bond-donor organocatalysis was initiated by the unexpected discovery that omitting the metal from an ostensibly metal-catalyzed Strecker reaction increased the enantioselectivity. Girard again:

The principle of originality at all costs leads to paralysis. The more we celebrate "creative and enriching" innovations, the fewer of them there are.

Langmuir’s example shows us a different path towards innovation. If we set out to investigate and address real-world problems of known practical import, without innovation in mind, Gilliam and Girard argue that we’ll be more innovative than if we make innovation our explicit goal. I don’t have a concrete policy recommendation to share here, but some of my other blog posts on applied research at MIT and the importance of engineering perhaps hint at what positive change might look like.

In accordance with the themes of this piece, my interpretation of Girard pretty much comes straight from Johnathan Bi. He has a lecture on Youtube where he discusses these ideas: here’s a link to the relevant segment, which is the only part I’ve watched.