13C NMR is, generally speaking, a huge waste of time.

This isn’t meant to be an attack on carbon NMR as a scientific tool; it’s an excellent technique, and gives structural information that no other methods can. Rather, I take issue with the requirement that the identity of every published compound be verified with a 13C NMR spectrum.

Very few 13C NMR experiments yield unanticipated results. While in some cases 13C NMR is the only reliable way to characterize a molecule, in most cases the structural assignment is obvious from 1H NMR, and any ambiguity can be resolved with high-resolution mass spectrometry. Most structure determination is boring. Elucidating the structure of bizarre secondary metabolites from sea sponges takes 13C NMR; figuring out if your amide coupling or click reaction worked does not.

The irrelevance of 13C NMR can be shown via the doctrine of revealed preference: most carbon spectra are acquired only for publication, indicating that researchers are confident in their structural assignments without 13C NMR. It’s not uncommon for the entire project to be scientifically “done” before any 13C NMR spectra are acquired. In most fields, people treat 13C NMR like a nuisance, not a scientific tool—the areas where this isn’t true, like total synthesis or sugar chemistry, are the areas where 13C NMR is actually useful.

Requiring 13C NMR for publication isn’t costless. The low natural abundance of 13C and poor gyromagnetic ratio means that 13C NMR spectra are orders of magnitude more difficult to obtain than 1H NMR spectra. As a result, a large fraction of instrument time in any chemistry department is usually dedicated to churning out 13C NMR spectra for publication, while people with actual scientific problems are kept waiting. 13C NMR-induced demand for NMR time means departments have to buy more instruments, hire more staff, and use more resources; the costs trickle down.

And it’s not like eliminating the requirement to provide 13C NMR spectra would totally upend the way we do chemical research. Most of our field’s history, including some of our greatest achievements, were done in the age before carbon NMR—the first 13C NMR study of organic molecules was done by Lauterbur in 1957, and it would take even longer for the techniques to advance to the point where non-specialists could use the technique routinely. Even in the early 2000s you can find JACS papers without 13C NMR spectra in the SI, indicating that it's possible to do high-quality research without it.

Why, then, do we require 13C NMR today? I think it stems from a misguided belief that scientific journals should be the ultimate arbiters of truth—that what’s reported in a journal ought to be trustworthy and above reproach. We hope that by requiring enough data, we can force scientists to do their science properly, and ferret out bad actors along the way. (Perhaps the clearest example of this mindset is JOC & Org. Lett., who maintain an ever-growing list of standards for chemical data aimed at requiring all work to be high quality.) Our impulse to require more and more data flows from our desire to make science an institution, a vast repository of knowledge equipped to combat the legions of misinformation.

But this hasn’t always been the role of science. Geoff Anders, writing for Palladium, describes how modern science began as an explicitly anti-authoritative enterprise:

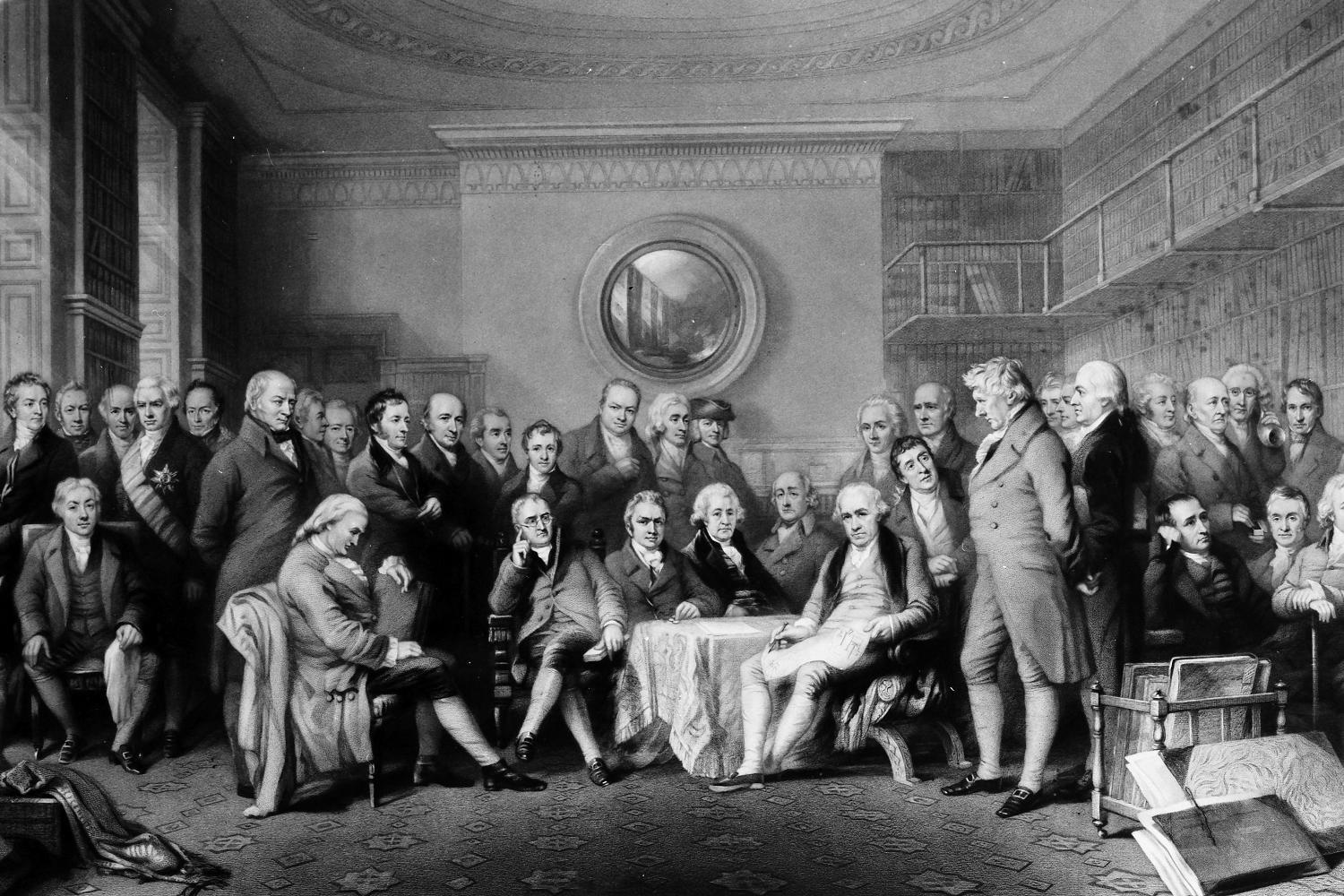

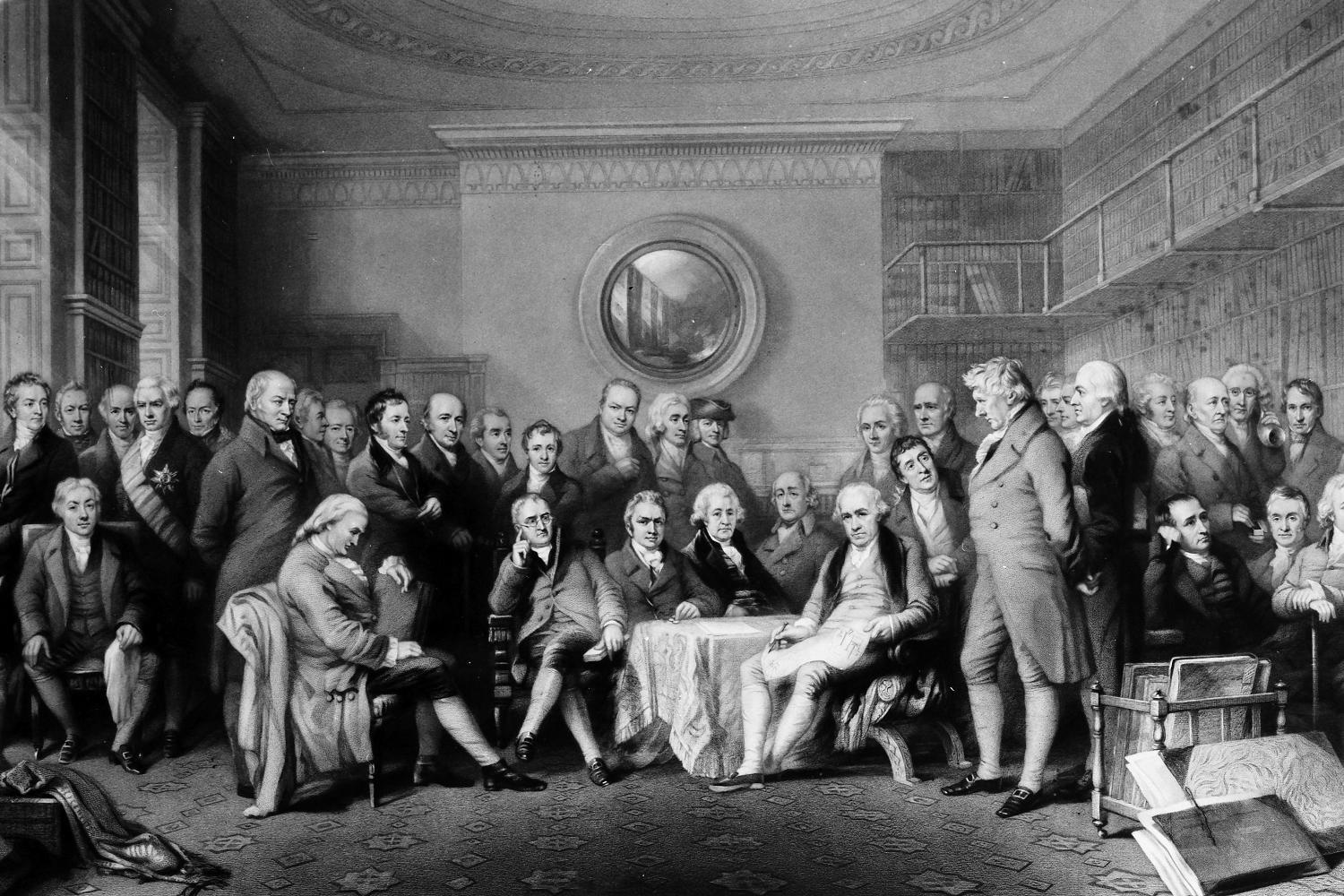

Boyle maintained that it was possible to base all knowledge of nature on personal observation, thereby eliminating a reliance on the authority of others. He further proposed that if there were differences of opinion, they could be resolved by experiments which would yield observations confirming or denying those opinions. The idea that one would rely on one’s own observations rather than those of others was enshrined in the motto of the Royal Society—nullius in verba.

nullius in verba translates to “take no one’s word for it,” not exactly a ringing endorsement of science as institutional authority. This same theme can be found in more recent history. Melinda Baldwin’s Making Nature recounts how peer review—a now-core part of scientific publishing—became commonplace at Nature only in the 1970s. In the 1990s it was still common to publish organic chemistry papers without supporting information.

The point I’m trying to make is not that peer review is bad, or that scientific authority is bad, but that the goal of enforcing accuracy in the scientific literature is a new one, and perhaps harder to achieve than we think. There are problems in the scientific literature everywhere, big and small. John Ioannidis memorably claimed that “most published findings are false,” and while chemistry may not suffer from the same issues as the social sciences, we have our own problems. Elemental analysis doesn’t work, integration grids cause problems, and even reactions from famous labs can’t be replicated. Based on this, we might conclude that we’re very, very far from making science a robust repository of truth.

Nevertheless, progress marches on. A few misassigned compounds here and there don’t cause too many problems, any more than a faulty elemental analysis report or a sketchy DFT study. Scientific research itself has mechanisms for error correction: anyone who’s ever tried to reproduce a reaction has engaged in one such mechanism. Robust reactions get used, cited, and amplified, while reactions that never work slowly fade into obscurity. Indeed, despite all of the above failures, we’re living through a golden age for our field.

Given that we will never be able to eradicate bad data completely, the normative question then becomes “how hard should we try?” In an age of declining research productivity, we should be mindful not only of the dangers of low standards (proliferation of bad work) but also of the dangers of high standards (making projects take way longer). There’s clear extremes on both ends: requiring 1H NMR spectra for publication is probably good, but requiring a crystal structure of every compound would be ridiculous. The claim I hope to make here is that requiring 13C NMR for every compound does more to slow down good work than it does to prevent bad work, and thus should be abandoned.

Update 12/16/2022: see some followup remarks based on feedback from Twitter.