This is the second in what will hopefully become a series of blog posts (previously) focusing on the fascinating work of Dan Singleton (professor at Texas A&M). My goal is to provide concise and accessible summaries of his work and highlight conclusions relevant to the mechanistic or computational chemist.

Today I want to discuss one of my favorite papers, a detailed study of the nitration of toluene by Singleton lab at Texas A&M.

This reaction, a textbook example of electrophilic aromatic substitution, has long puzzled organic chemists. The central paradox is that intermolecular selectivity is typically quite poor between different arenes, but positional selectivity is high—implying that NO2+ is unable to recognize more electron-rich arenes but somehow still able to recognize more electron-rich sites within a given arene.

George Olah devoted considerable effort to studying this paradox:

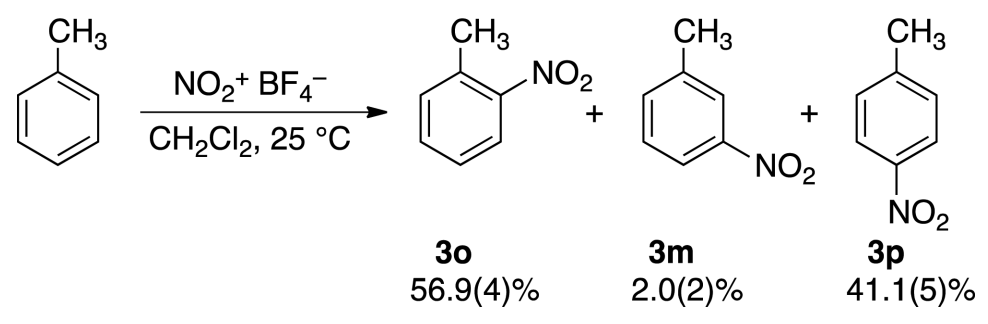

Kuhn and I have subsequently developed a new efficient nitration method by using stable nitronium salts (like tetrafluoroborate) as nitrating agents. Nitronium salt nitrations are also too fast to measure their absolute rates, but the use of the competition method showed in our work low substrate selectivity, e.g., kt/kb of 1-2. [In other words, competition experiments show at most a 2-fold preference for toluene.] On the basis of the Brown selectivity rules, if these fast reactions followed σ-complex routes they would also have a predictably low positional selectivity (with high meta isomer content). However, the observed low substrate selectivities were all accompanied by high discrimination between available positions (typical isomer distributions of nitrotoluenes were (%) ortho:meta:para = 66:3:31). Consequently, a meta position would seem to be sevenfold deactivated compared to a benzene position, giving a partial rate factor of mf = 0.14. These observations are inconsistent with any mechanism in which the individual nuclear positions compete for the reagent (in the σ-complex step).

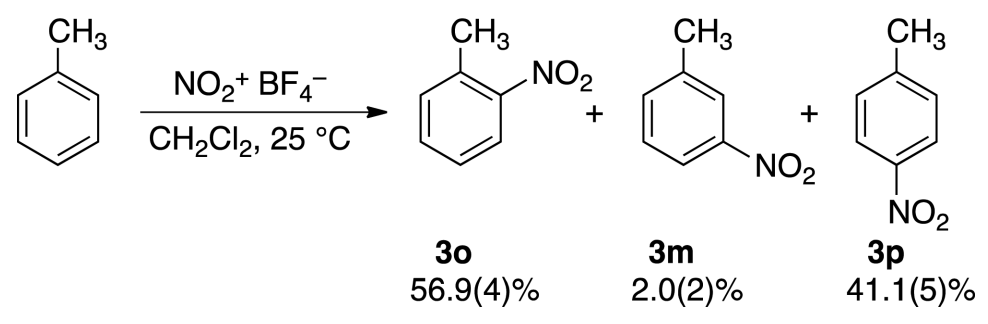

In explanation, we suggested the formation of a π complex in the first step of the reactions followed by conversion into σ complexes (which are of course separate for the individual ortho, para, and meta positions), allowing discrimination in orientation of products. (ref, emphasis added)

His conclusion, summarized in the last sentence of the above quote, was that two different sets of complexes were involved: π complexes which controlled arene–arene selectivity, and σ complexes which controlled positional selectivity. Thus, the paradox could be resolved simply by invoking different ∆∆G‡ values for the transition states leading to π- and σ-complex formation. The somewhat epicyclic nature of this proposal led to pushback from the community, and (as Singleton summarizes) no cogent explanation for this reactivity had yet been advanced at the time of writing.

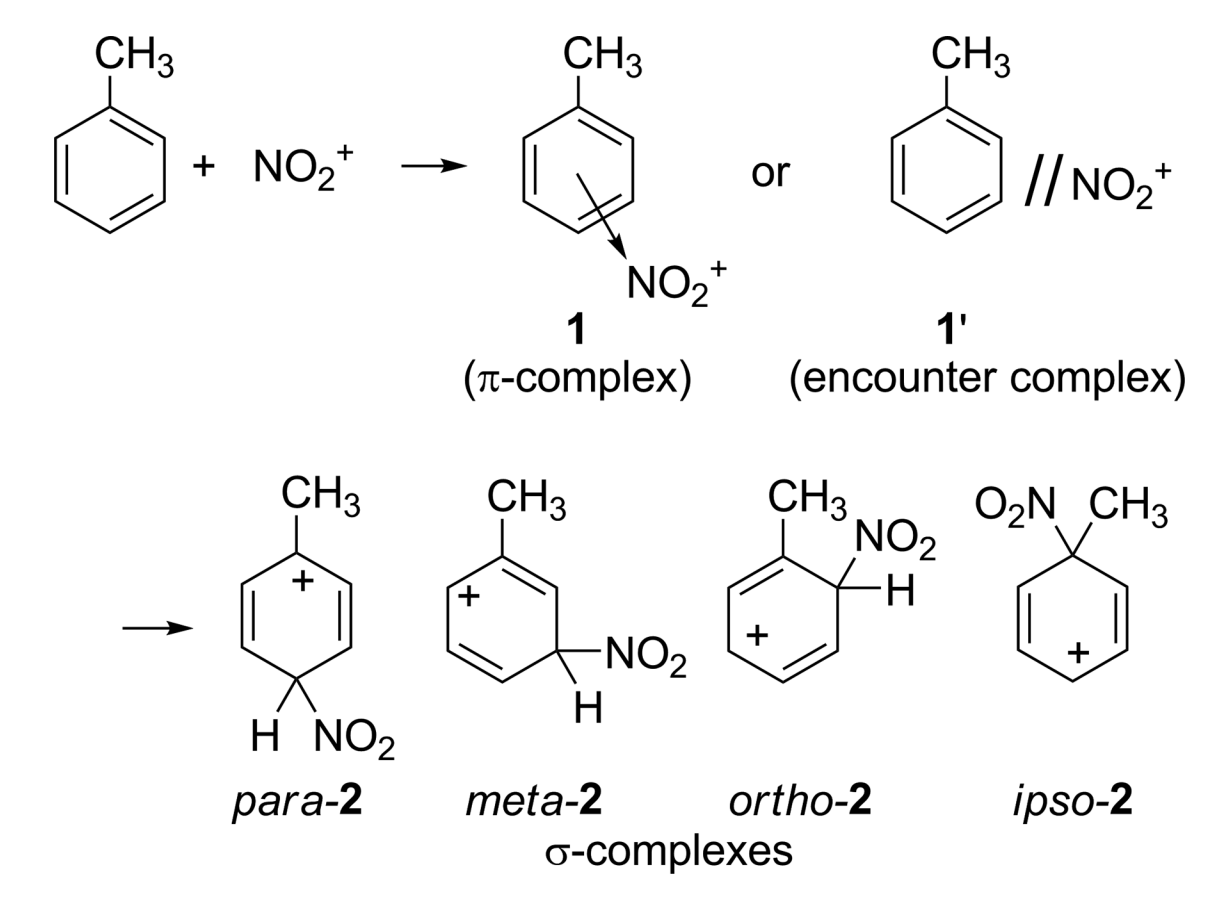

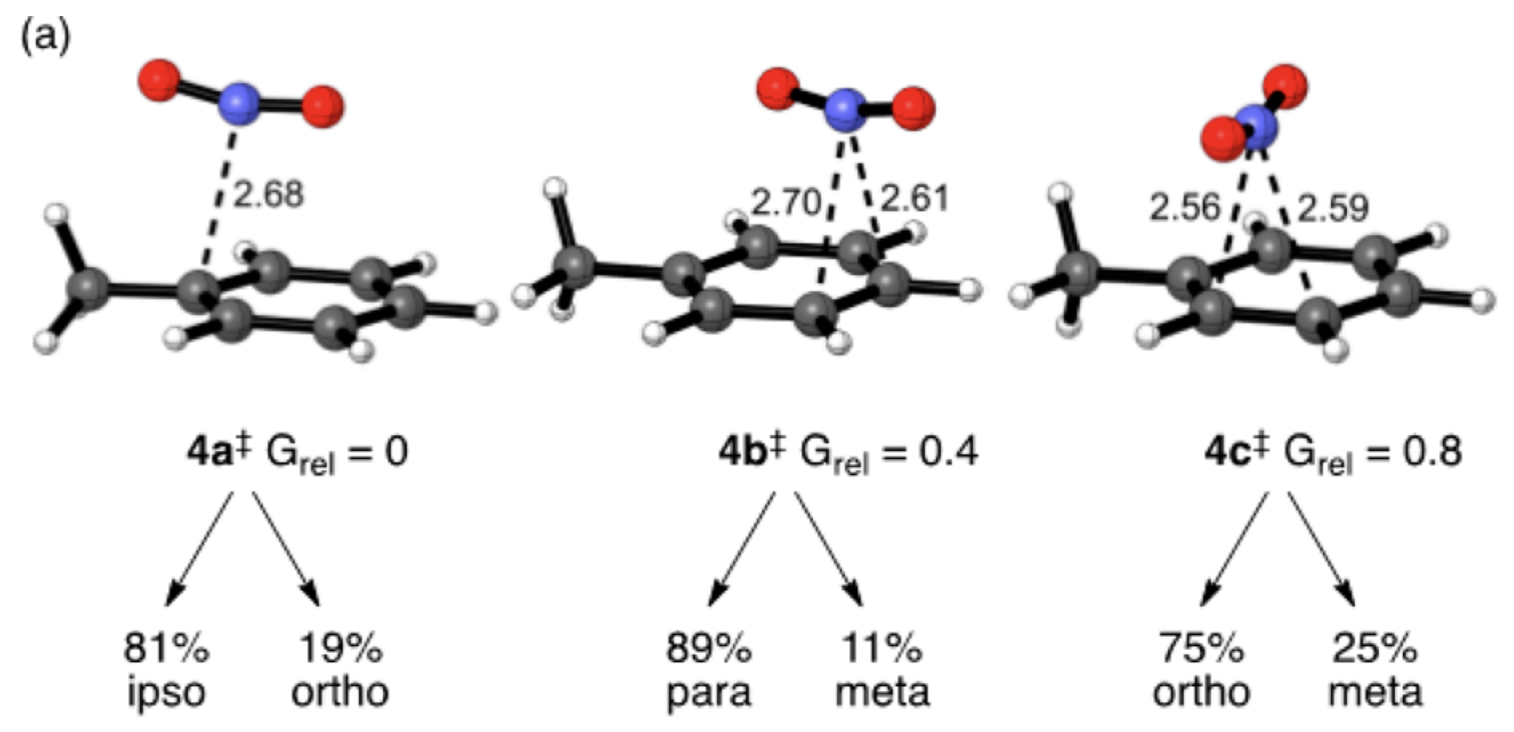

The authors of this paper initiated their studies of this reaction by performing an extensive series of “traditional” DFT calculations in implicit solvent. M06-2X/6-311G(d) was chosen by benchmarking against coupled-cluster calculations, and the regiochemistry was examined with a variety of computational methods.

In the absence of BF4-, naïve calculations predict entirely the wrong result: the para product is predicted to be more favorable than the ortho product, and no meta product is predicted to form at all. However, closer examination of the transition states reveals post-transition-state bifurcation in each case: for instance, the “para” transition state actually leads to para/meta in a 89:11 ratio. When all possible bifurcations for all transition states are taken into account in a Boltzmann-weighted way, the results remain wrong: para is still incorrectly favored over ortho, and meta is now predicted to form in a much higher proportion than observed.

The authors examine various potential resolutions of this problem, including inclusion of BF4-, use of explicit solvent within an ONIOM scheme, and other nitration systems which might lead to more dissociated counterions. These methods lead to different, but equally wrong, conclusions.

They then perform free energy calculations to determine the energetics of nitronium approach to toluene (in dichloromethane). Surprisingly, no barrier exists to NO2+ attack: once nitronium comes within 4.5 Å of the arene, it is “destined to form some isomer” of product (in the authors’ words). Singleton and Nieves-Quinones dryly note:

…The apparent absence of transition states (more on this later) after formation of the encounter complex has never previously been suggested. This absence is in fact counter to basic ideas in all previous explanations of the selectivity.

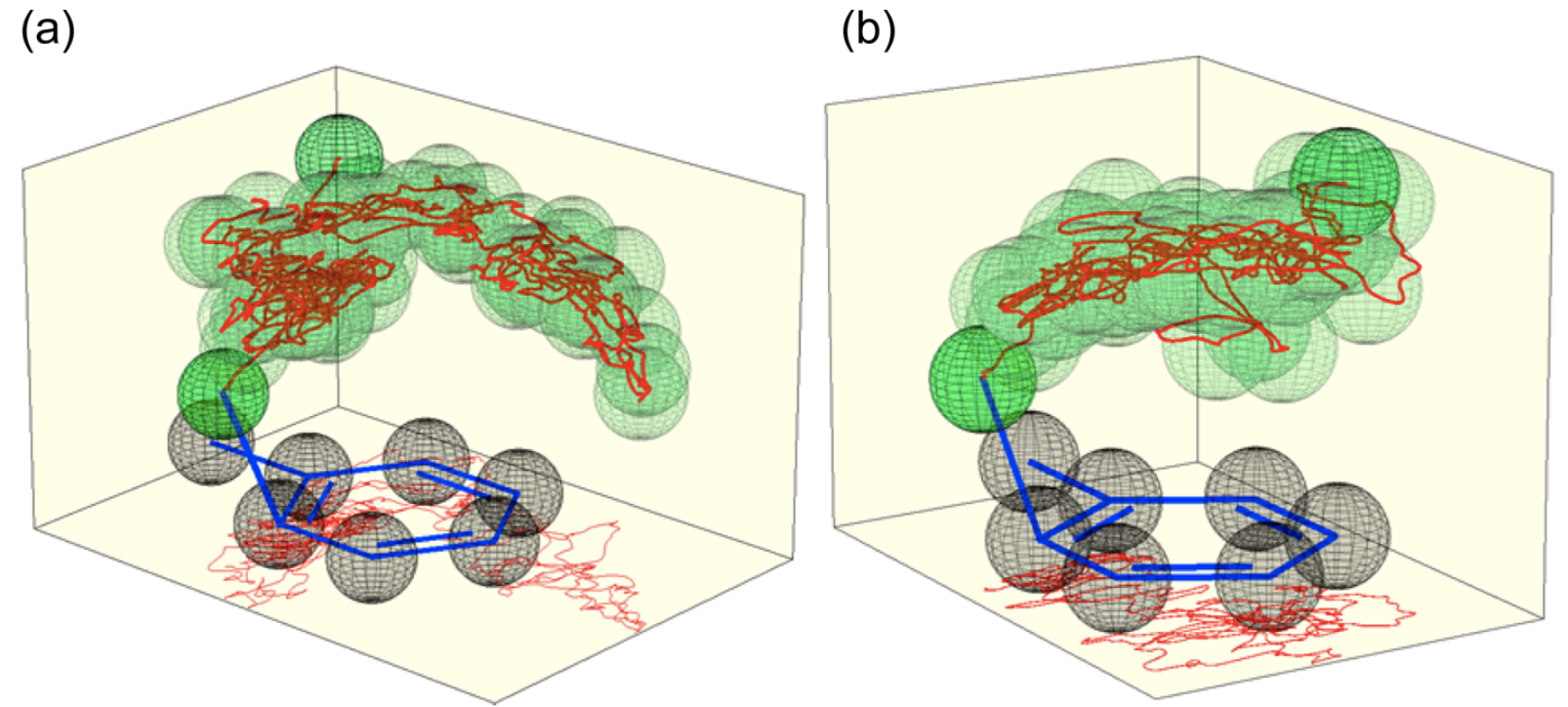

This observation explains one horn of the dilemma—why selectivity between different arenes is low—but leaves unanswered why positional selectivity is so high. To examine this question, the authors then directly run reactions in silico by using unconstrained ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) and observe the product ratio. The product ratio (45:2:53 o/m/p) they observe matches the experimental values (41:2:57 o/m/p) almost perfectly!

With this support for the validity of the computational model in hand, the authors then examine the productive trajectories in great detail. Surprisingly, they find that although no barrier exists to nitronium attack, the reaction is relatively slow to proceed, taking on average of 3.1 ps to form the product. Trajectories lacking either explicit solvent or tetrafluoroborate lack both this recalcitrance and the observed selectivity: instead, nitronium opportunistically reacts with the first carbon it approaches. This suggests that selectivity is only possible when the nitronium–toluene complex is sufficiently persistent.

The authors attribute the long life of the NO2+—toluene complex to the fact that the explicit solvent cage must reorganize to stabilize formation of the Wheland intermediate. This requires both reorientation of the dichloromethane molecules and repositioning of the tetrafluoroborate anion, which both occur on the timescale of the trajectories (ref). Accordingly, the reaction is put on hold while cage reorganization occurs, giving NO2+ time to preferentially attack the ortho and para carbons. (I would be tempted to call the π complex a dynamic/entropic intermediate, in the language of either Singleton or Houk.)

This computational picture thus accurately reproduces the experimental observations and explains the initial paradox we posed: selectivity does not arise through competing transition state energies, but through partitioning of a product-committed π complex which is prevented from reacting further by non-instantaneous solvent relaxation. Since similar π complexes can be formed under almost any nitration conditions, this proposal explains the often similar selectivities observed with other reagents or solvents.

More philosophically, this proposal explains experimental results without invoking any transition states whatsoever. In their introduction, the authors quote Gould as stating:

If the configuration and energy of each of the intermediates and transition states through which a reacting system passes are known, it is not too much to say that the mechanism of the reaction is understood.

While this may be true to a first approximation in most cases, Singleton and co-workers have demonstrated here that this is not true in every case. This is an important conceptual point. As our ability to study low-barrier processes and reactive intermediates grows, I expect that we will more clearly appreciate the limitations of transition-state theory, and have to develop new techniques to interpret experimental observations.

But perhaps the reason I find this paper most exciting is simply the beautiful match between theory and experiment for such a complex and seemingly intractable system. This work not only predicts the observed reaction outcomes under realistic conditions, but also allows (through AIMD) the complete analysis of the entire reaction landscape in exquisite detail, from approach to post-bond-forming steps. In other words, this is a mechanistic chemist’s dream: a perfect movie of the entire reaction’s progress, from beginning to end. Go and do likewise!

Thanks to Daniel Broere and Joe Gair for noticing that "electrophilic aromatic substitution" was erroneously written as "nucleophilic aromatic substitution." This embarassing oversight has been corrected.