This is the first in what will hopefully become a series of blog posts focusing on the fascinating work of Dan Singleton (professor at Texas A&M). My goal is to provide concise and accessible summaries of his work and highlight conclusions relevant to the mechanistic or computational chemist.

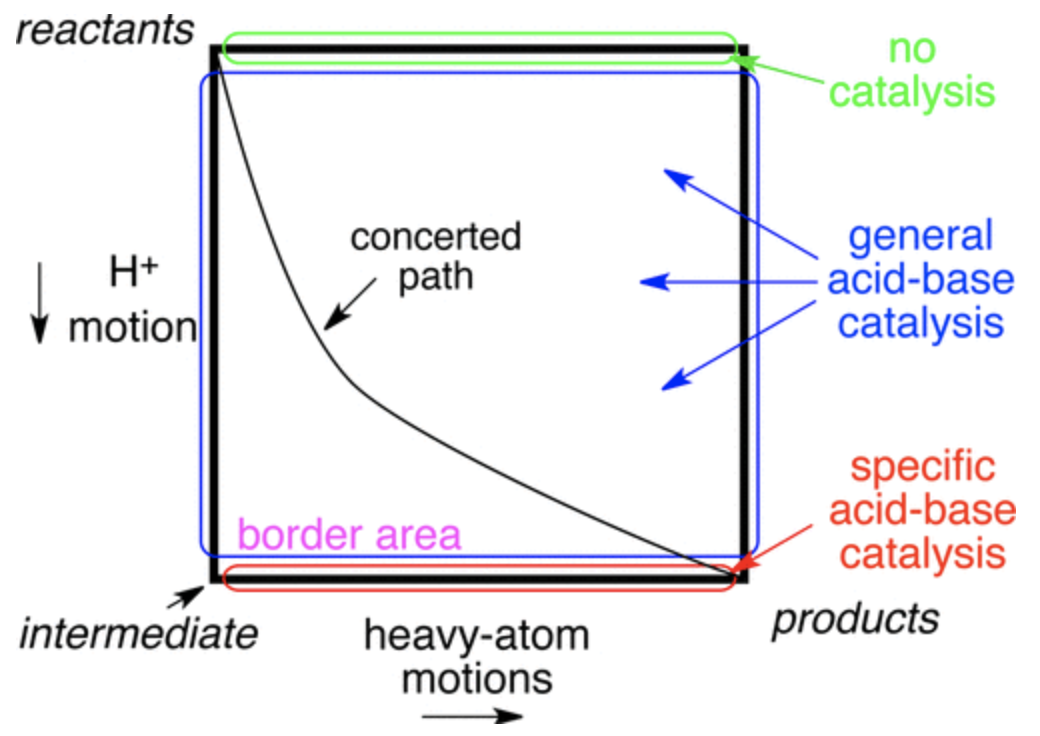

A central theme in mechanistic chemistry is the question of concertedness: if two steps occur simultaneously (“concerted”) or one occurs before the other (“stepwise”). One common way to visualize these possibilities is to plot the reaction coordinate of each step on two axes to form a 2D More O’Ferrall–Jencks (MOJ) plot. On an MOJ plot, a perfectly concerted reaction looks like a straight line, since the two steps occur together, while a stepwise reaction follows the border of the plot, with an intermediate located at one of the corners:

In the context of acid catalysis, where a Brønsted acid activates a substrate towards further transformations, the concerted mechanism is known as “general-acid catalysis” and the stepwise mechanism is known as “specific-acid catalysis.” This case is particularly interesting because the timescales of heavy-atom motion and proton motion are somewhat different, as can be seen by comparing typical O–H and C–O IR stretching frequencies:

1/(3500 cm-1 * 3e10 cm/s) = 9.5 fs for O–H bond vibration

1/(1200 cm-1 * 3e10 cm/s) = 28 fs for C–O bond vibration

Since these timescales are so different, it’s impossible for the two steps to proceed perfectly synchronously, since the proton transfer will be done before heavy-atom motion is even half complete; in other words, the slope of the reaction’s path on the MOJ diagram can’t be 1. Ceteris paribus, then, one might expect stepwise specific-acid mechanisms to be favored. In some cases, however, the putative intermediate would be so unstable that its lifetime ought to be roughly zero (an enforced concerted mechanism, to paraphrase Jencks).

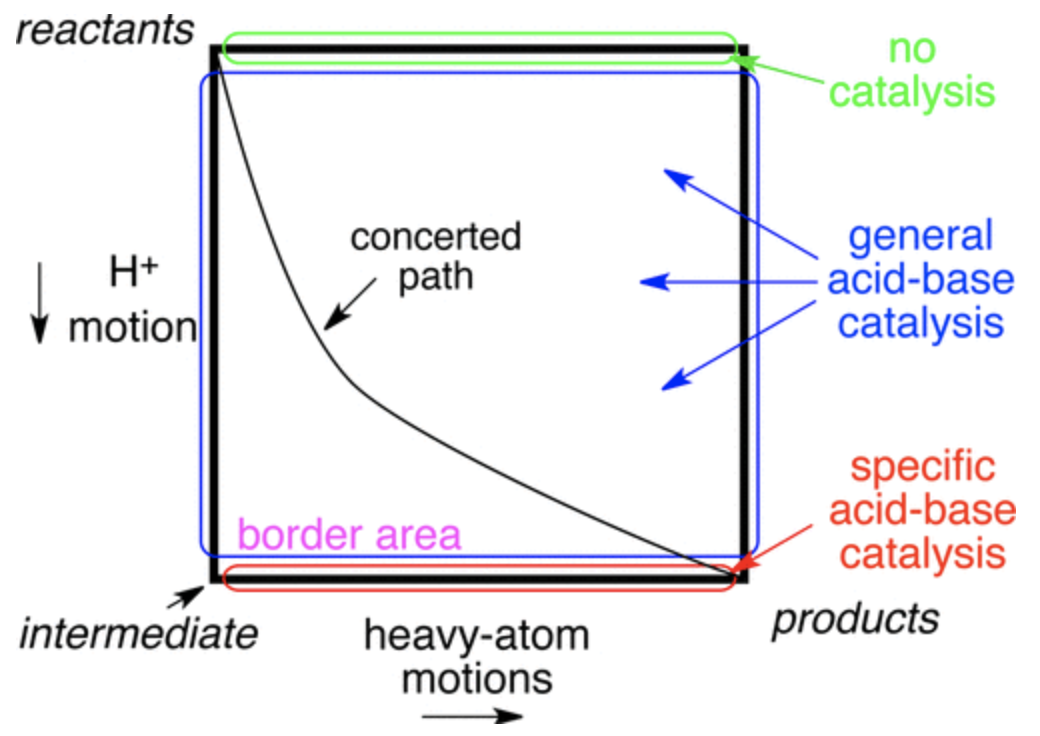

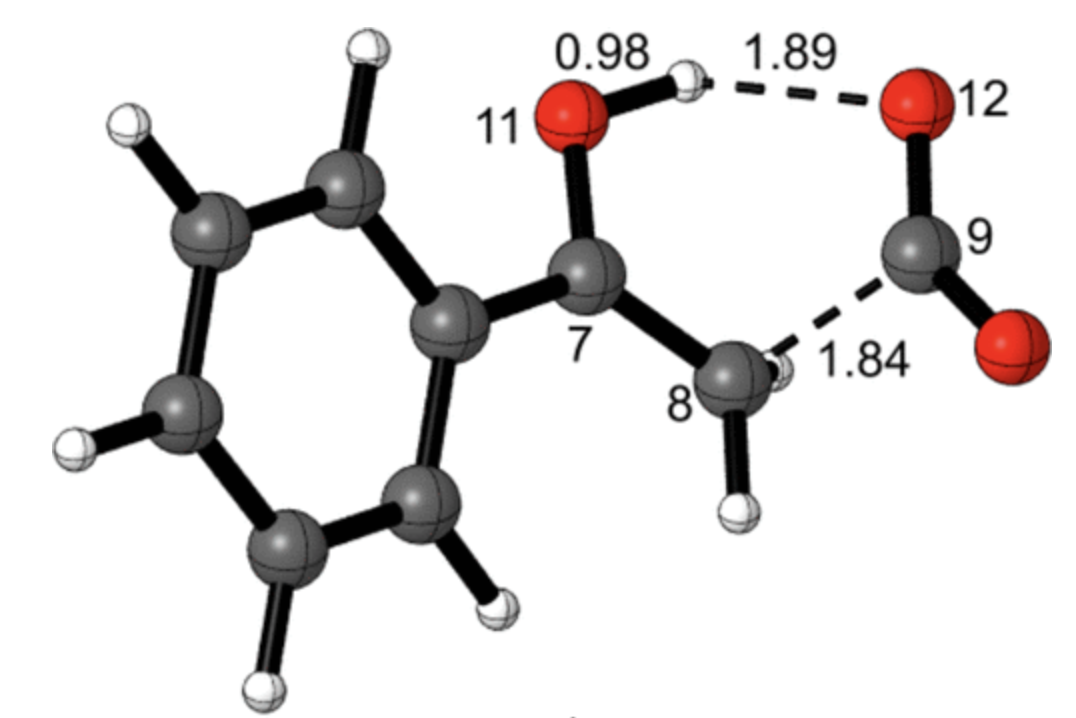

In this week's paper, Aziz and Singleton investigate the mechanism of one such example, the decarboxylation of benzoylacetic acid, which in the stepwise limit proceeds through a bizarre-looking zwitterion:

Distinguishing concerted and stepwise mechanisms is, in general, a very tough question. In rare cases an intermediate can actually be observed spectroscopically, but inability to observe the intermediate proves nothing: the intermediate could be 10 kcal/mol above the ground state (leading to a vanishingly low concentration) or could persist only briefly before undergoing subsequent reactions. Accordingly, other techniques must be used to study the mechanisms of these reactions.

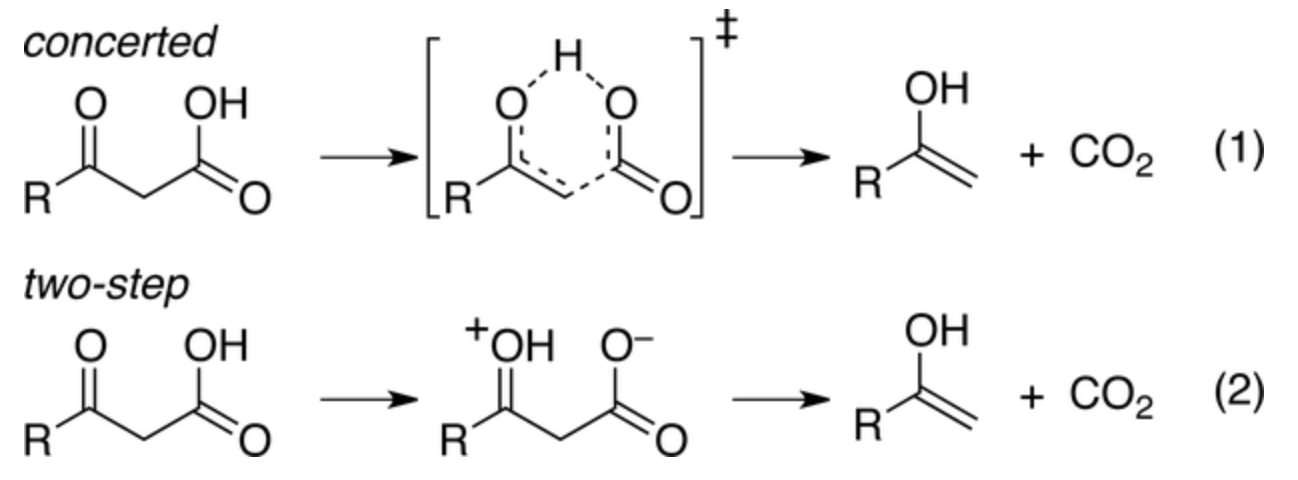

In this case, the authors measured the 12C/13C kinetic isotope effects using their group’s natural abundance method. Heavy-atom kinetic isotope effects are one of the best ways to study these sorts of mechanistic questions because isotopic perturbation is at once extremely informative and very gentle, causing minimal perturbation to the potential energy surface (unlike e.g. a Hammett study). The KIEs they found are shown below:

These KIEs match the computed structure shown below nicely, which shows that proton transfer precedes C–C bond breaking:

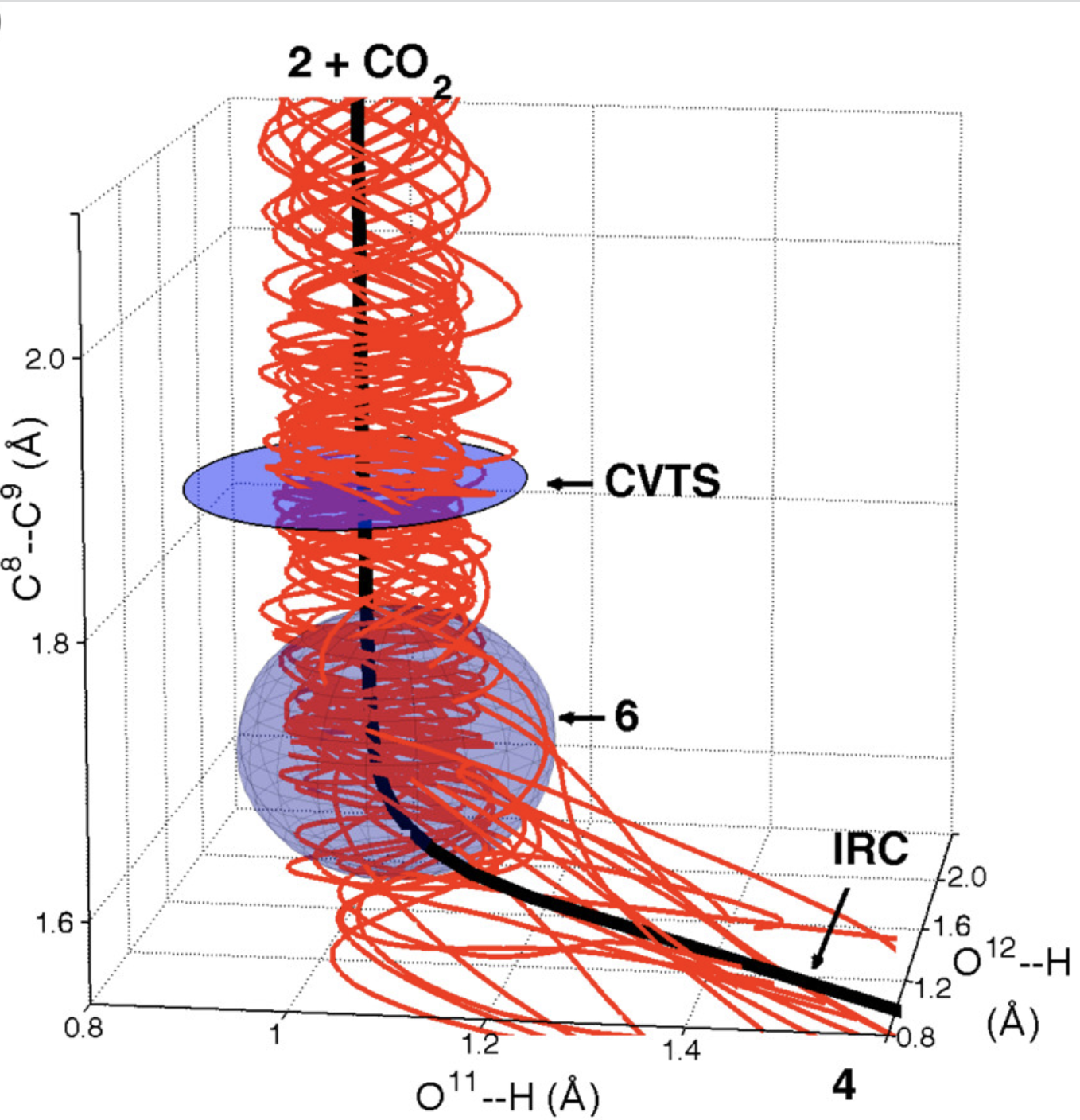

To probe the stepwise/concerted nature of this reaction, the authors conducted quasiclassical ab initio molecular dynamics, propagating trajectories forwards and backwards from the transition state. Surprisingly, the dynamics show that proton transfer is complete before C–C bond scission occurs, forming an intermediate (6) which persists for, on average, 3.4 O–H bond vibrations despite not being a minimum on the PES. This reaction therefore inhabits the border between general- and specific-acid catalysis—proton transfer does occur before decarboxylation, but the intermediate species (in the nomenclature of Houk and Doubleday, a “dynamic intermediate”) is incredibly ephemeral.

This surprising scenario occurs because of the different timescales of the two elementary mechanistic steps, as discussed above. In the words of the authors:

It is well understood in chemistry that concerted multibond reactions often involve highly asynchronous bonding changes. However, the normal understanding of asynchronous concerted reactions is that the bonding changes overlap. If otherwise, why should the reaction be concerted at all? This view fails to take into account the differing physics of the heavy-atom versus proton motions. Because of the uneven contribution of the motions, their separation is arguably intrinsic and unavoidable whenever the reaction is highly asynchronous. (emphasis added)

Aziz and Singleton also observe a curious phenomenon in the quasiclassical trajectories, wherein some trajectories initiated backwards from the (late) transition state fully form the C–C bond before reverting to enol + CO2. This phenomenon, termed “deep recrossing,” occurs because the oxygen of the carboxylate is unable to receive the proton, stalling the reaction in the region of the unstable zwitterion; unable to progress forward, the species simply extrudes CO2 and reverts back to the enol. Thus, even though the O–H bond is formed after the C–C bond (in the reverse direction) and little O–H movement occurs in the TS, inability to form the O–H bond prevents productive reaction, just like one might expect for a concerted TS.

The picture that emerges, then, is a reaction which “wants” to be concerted, owing to the absence of a stable intermediate along the reaction coordinate, but ends up proceeding through a stepwise mechanism because of the speed of proton transfer. Importantly, the dynamic intermediate “undergoes a series of relevant bond vibrations, as would any intermediate, and it can proceed from this structure in either forward or backward directions”: it is, in meaningful ways, an intermediate.

Given the ubiquity of proton transfer in organic chemistry, it is likely that many more reactions proceed through this sort of rapidly stepwise mechanism than is commonly appreciated. One case which I find particularly intriguing is “E2” reactions, which typically feature proton transfer to a strong base (e.g. potassium tert-butoxide) at the same time as C–Br or C–I bond dissociation. How do these reactions actually proceed on the femtosecond timescale? Is it possible that, as Bordwell proposed, many E2 reactions are actually stepwise? So much remains to be learned.