TW: stridently anti–Roman Catholic rhetoric, medieval realist metaphysics

Popular histories of the Reformation typically emphasize the discontinuity between medieval theology and the Reformers. In its simplest form, an account of church history through the Reformation might go like this:

This outline, while basic, is accepted by many Catholics and Protestants. A Catholic might tell the story like this (with apologies to John Henry Newman):

Just like an acorn grows into an oak tree, so do the doctrines of the Church grow out of the kernel of Scripture. The church spent over a millenium carefully developing a body of doctrine and theology (guided by the Holy Spirit)—until the “wild boar” Luther and other Reformers decided, in their arrogance, to start from scratch and reinterpret Scripture according to their own ideas.

This is pretty close to actual Roman-Catholic writings. For instance, Hillare Belloc writes in The Great Heresies that Calvin was “the founder of a new religion“ and the author of “a complete new theology, strict and consistent” that was “in opposition to the ancient body of doctrine by which our fathers had lived.”

In contrast, a Protestant might tell the story like this:

While the early church held to simple doctrines of holiness and righteousness, the institutionalization of Christian thought and the bizarre power structures of the medieval church led to centuries of theological speculation with no Scriptural backing and no real relevance to Christianity as exemplified by Christ. The Reformers returned the church to the simplicity and Bible-centeredness of the early church, thus setting people free from a millenium of papal tyranny.

Although these two tellings are obviously different in framing, both conform to the basic storyline outlined above.

Matthew Barrett is here to tell you that this story is completely wrong. In his book The Reformation As Renewal, Barrett argues that the Reformers saw themselves in continuity with the historical church, not opposed to it. In fact, Barrett argues that today’s “Protestants” are actually the true descendents of the universal “catholic” church (p. 883):

…in Luther’s own mind, his call to reform was not a summons to something modern. His vision for renewal was catholic. Debate may persist over the success of that vision, but no debate should exist over its self-professing identity. In Luther’s own words, “Thus we have proven that we are the true, ancient church, one body and one communion of saints with the holy, universal, Christian church.”

If Protestants today desire fidelity to the history of their own genesis, then they should listen to one of the Reformation’s heirs, Abraham Kuyper: “A church that is unwilling to be catholic is not a church, because Christ is the savior not of a nation, but of the world… We cannot therefore, without being untrue to our own principle, abandon the honorable title of ‘catholic’ as though it were the special possession of the Roman Church.”

What defines a true adherence to Protestantism? To be Protestant is to be catholic. But not Roman.

(Barrett’s using “catholic” here to describe continuity with the historical and universal church; in contrast, “Catholic” or “Roman Catholic” implies submission to the Roman Curia. I’ll try to preserve this distinction throughout this post.)

Barrett’s claim is certain to offend Roman Catholics, and the book is indeed thoroughly anti-Catholic (as befits any Protestant history of the Reformation). But Barrett’s real goal is to convince contemporary Protestants that historical Christian theology is good and worthy of study. He wants Protestants to claim “sounder Scholastics” like Aquinas as part of their tradition—and, where necessary, to be willing to learn from their teachings when they depart from contemporary ideas.

His book is long and wandering. While The Reformation As Renewal roughly follows the intellectual history of the Reformation, Barrett alternates between history of philosophy, historical and biographical sections, and theological polemics (sometimes within the same chapter). To keep this review short-ish and interesting, I’m going to pull out some of the most compelling ideas without necessarily following Barrett’s organization; interested readers should just read the original book.

(To disclaim any potential conflicts of interest: I’m a Reformed-ish low-church Protestant who, while friends with many Roman Catholics, generally disagrees with their theology. I’ll occasionally refer to Protestants as “we” in this post; skeptical or Catholic readers are welcome to excuse themselves from this pronoun.)

Before I jump into the review: the “history of philosophy” component of The Reformation as Renewal is a big part of Barrett’s construction, but might be hard to follow if you’re not already somewhat familiar with the field. Some brief terms:

Without further ado, then, here are seven ideas that I thought were interesting from The Reformation as Renewal.

Of all the competing Greek philosophical schools that existed before Christianity, Platonism proved the best match for Christian thought. Barrett quotes Augustine as saying that the Platonists have been “raised above the rest [of the philosophers] by a glorious reputation they so thoroughly deserve” because of how they have “raised their eyes above all material objects in their search for God” (p. 218).

While anti-Christian accounts of the early church often cast Christianity as the syncretic offspring of Judaism and neo-Platonism, Barrett disagrees. He argues that Christians adopted the framework and vocabulary of neo-Platonism but not the conclusions—it was Plato’s “transcendent map of reality” (p. 217) which Christians adopted, and not his entire worldview. Following Hans Boersma, Barrett identifies five key distinctives of medieval via antiqua Christian Platonism (pp. 226–227, emphases added):

- Anti-materialism. Christian Platonism claims that bodies and their properties are not the only things that exist.

- Anti-mechanism. Christian Platonism maintains that the natural order (including, therefore, physical events), cannot be fully explained by physical or mechanical causes.

- Anti-nominalism. Christian Platonism argues that reality is made up not just of individuals, each uniquely situated in time and space, but that two individual objects can be the same in essence (e.g., both being canine) while still being unique individuals (distinct dogs).

- Anti-relativism. Christian Platonism rejects the notion, both in terms of knowledge and morals, that human beings are the measure of all things, suggesting instead that goodness is a property of being.

- Anti-skepticism. Christian Platonism maintains that the real can in some manner become present to us, so that knowledge is within reach.

To complement the “polemical posture” (p. 227) of this list, Barrett identifies the idea of a “participation metaphysic” as a key positive belief of Christian Platonism. In accordance with Paul’s address at Mars Hill (Acts 17), Christians believe that we “live and move and have our being” in God. Medieval Christian Platonists believed that “the soul can share in the higher level of reality it seeks to know” and that “all true knowledge of the divine, the eternal, and the really real is an exercise in communion” (p. 228).

Barrett thinks that the via antiqua was pretty much correct. Unfortunately, late-medieval theologians like Duns Scotus and William of Ockham “cut the tapestry of participation and dispensed with the fabric of a realist metaphysic” (p. 228) in favor of nominalism. Duns Scotus believed that God had a libertarian freedom to do whatever he wanted (“voluntarism”), elevating God’s will above God’s intellect and, according to Barrett, eroding the realist metaphysic of earlier Scholastic thinkers like Aquinas.

William of Ockham took this a step further by denying the existence of universals (p. 251), leading ultimately to the voluntarist via moderna of Gabriel Biel, which described justification as God’s voluntary acceptance of man’s good works, which—although they don’t intrinsically merit God’s favor—are accepted as sufficient through God’s grace. While this might not quite constitute Pelagianism, it’s certainly not too far.

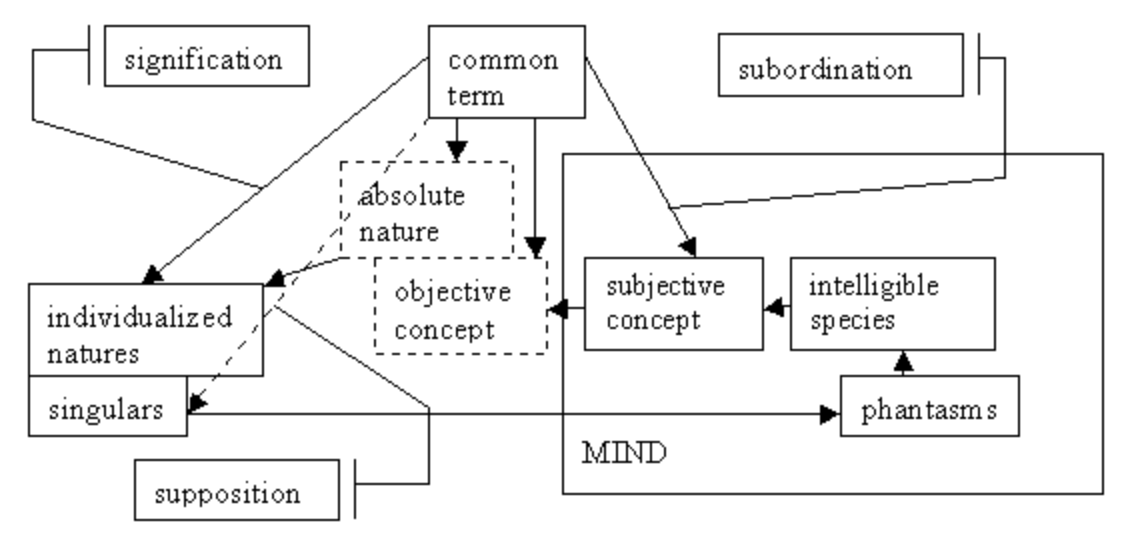

Barrett argues that this “decayed” (p. 283) nominalist late-medieval Scholasticism was the prevailing theological context for the Reformation, and that the Reformers can be understood as rejecting the via moderna in favor of returning to the via antiqua of older Scholastics like Anselm and Aquinas. I’ll confess that I find the detailed metaphysics somewhat difficult to parse here, even with helpful diagrams from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

As a single explanation for the Reformation, this philosophical line of argumentation is a bit too neat: while the Reformers may have disliked the nominalist via moderna, there was plenty else about the late medieval church that provoked protest, including corruption, indulgences, bad preaching, politics, and so on.

But this line of thinking helps Barrett to explain why the Reformers can agree with Aquinas and earlier Scholastics on so much while writing firmly anti-Scholastic works like Disputation Against Scholastic Theology (Luther, 1517). Barrett argues that the target of Reformation ire was not “all of historical theology” but instead a distinct philosophical movement which, while dominant in the early 1500s, had broken from Church tradition. By rejecting Biel and the via moderna, Barrett claims that the Reformers were actually returning to the tradition of the universal “catholic” church.

(As an aside, I didn’t realize how much some modern-day Christians hated Duns Scotus—according to John Milbank, Duns Scotus was “the turning point in the destiny of the West” and the ultimate author of all sorts of modernist heresies.)

The Reformation is often taught as a separate movement from the Italian Renaissance, but Barrett argues that we should see the Reformation as essentially a part of the Renaissance (p. 312, emphasis original):

It is reasonable to ask whether the Reformation was even possible apart from the prior advances of the Renaissance. Rather than labeling the Reformation a “new epoch different from, and in a sense opposed to, the Renaissance” it is better to “consider the Reformation as an important development within the broader historical period which… we continue to call… the Renaissance.”

Both movements were driven by a resurgence of interest in classical texts and ideas, as exemplified by humanist thinkers like Erasmus of Rotterdam (p. 313):

Few Reformers if any could claim they operated within a cultural or ecclesiastical context sanitized from the effects of humanism. Ready access to the Greek text of Erasmus, fresh translations of classical texts, renewed attention to inner spirituality, and ecclesiastical renovation—these and many other factors were advantageous to the advent of the Reformation.

For the Reformers, this meant going ad fontes (back to the sources) and discovering that church fathers like Augustine held beliefs that were at odds with current church doctrine (p. 320, emphases original):

Erasmus’s Greek New Testament gave Luther an opportunity to return to the text afresh and consider whether the soteriology [salvation theology] he imbibed was indeed scriptural. Yet Luther’s breakthrough discovery of justificatio sola fide was due not only to his renewed reading of Paul’s epistles and the Psalms, but also to his study of the corpus of Augustine. It is not an overstatement to say that Augustine’s doctrine of grace set Luther free. Ad fontes was the key that unlocked that discovery.

While Barrett is far from the first person to connect the Renaissance and the Reformation, I thought his discussion of the common intellectual threads tying these movements together was interesting and useful.

Barrett points out that the Reformers didn’t disagree with mainstream medieval Christian doctrine in the vast majority of areas—instead, they had specific criticisms about soteriology and ecclesiology.

Soteriology is the study of salvation. As discussed above, Catholic theologians like Gabriel Biel emphasized a voluntarist view of salvation in which God chose to reward good works with grace. In contrast, Luther and other Reformers argued that salvation was solely the result of faith (sola fide), and that God imputes righteousness to believers based on faith. (Although Calvin gets popular credit for being “the predestination guy,” Luther was committed to this point as well, as demonstrated by his 1525 work On the Bondage of the Will.)

This view of salvation was, according to Barrett, in accordance with previous church teachings. He quotes Luther as discovering salvation sola fide in Augustine’s The Spirit and the Letter, where Luther found “contrary to hope” that Augustine “interpreted God’s righteousness… as the righteousness with which God clothes us when he justifies us” (pp. 389–390), in contrast to the works-based soteriology of the Roman church.

The debate over soteriology quickly escalated into a debate about ecclesiology (or the study of the church). The popes argued that only they could authoritatively incorporate Scripture and that their interpretation was thus correct by definition; in contrast, the Reformers argued that papal views were in contrast with church history. In Barrett’s words (p. 415):

Rome elevated tradition to a second source of revelation, sometimes even a superior source. Luther and the Reformers, by contrast, believed tradition was an authority, but a ministerial authority, subservient to Scripture, its magisterial authority.

These debates are well-known and can be found in any history of the Reformation. What Barrett wants to show is that these are relatively specific debates. There are many other areas of theology where the Reformers could have broken with the theological status quo and didn’t. To quote Barrett (pp. 142–143, emphases original but paragraph break added):

…the continuity between the Scholastics and the Reformers dwarfs their discontinuity. For example, in Prima Pars [of the Summa Theologica] Thomas [Aquinas] treated the knowledge of God, the inspiration of Scripture, the existence of God, divine perfections, the Trinity, creation ex nihilo, the imago Dei, the human soul, divine providence, angels, and more. By and large, the Reformers did not need to address these loci, some of which were essential to orthodoxy. To do so in front of Rome could have thrown into question their own orthodoxy.

By contrast, Rome and Reformers alike agreed on classical theism’s articulation of these tenets… The point deserves emphasis: Scholastics like Thomas constructed a massive foundation grounded in classical Christian orthodoxy, and the Reformers never felt the need to address a majority of its loci because to disagree was to diverge from orthodoxy itself and its accompanying theological parameters. Their silence should not be taken as divergence but conformity, a quiet testimony to their catholicity. That should change current perspectives which so major [sic?] on discontinuity that the massive amount of continuity is either neglected or denied.

Barrett argues that the similarities between the Reformers and church fathers like Aquinas far outweigh their differences, and by extension that Protestants today should see themselves as largely in communion with Aquinas and other patristic or medieval Christian thinkers.

To show that the Reformers thought that they were aligned with historical Christian tradition, Barrett cites from their own works at length. In his response to Cardinal Jacopo Sadaleto, Calvin writes that “our [Protestant] agreement with antiquity is far closer than yours” and that the Reformation was an attempt “to renew that ancient form of the Church, which, at first sullied and distorted by illiterate men of indifferent character, was afterwards flagitiously mangled and almost destroyed by the Roman Pontiff and his faction” (pp. 2–3). Calvin goes on to accuse the Roman church of disgracing the memory of the true Christian church (p. 4):

Where, pray, exist among you any vestiges of that true and holy discipline which the ancient bishops exercised in the Church? Have you not scorned all their institutions? Have you not trampled all the canons under foot? Then, your nefarious profanation of the sacraments I cannot think of without the utmost horror.

Similarly, Luther vigorously affirms that “Protestant” Christianity, and not Roman Catholicism, is in continuity with the ancient and true Church (pp. 4–5):

…when Henry of Braunschweig accused Luther of betraying the church universal with innovation and heresy, Luther became furious. “They allege that we have fallen away from the holy church and set up a new church.” No, Luther said in response, “We are the true ancient church… you have fallen away from us.”

These quotes illustrate, at a minimum, that the Reformers did not believe the “pop” view of the Reformation I outlined in my introduction. Luther believed that him and his fellow Protestants “belong to the ancient church and are one with it… for whoever believes as the ancient church did and holds things in common with it belongs to the ancient church” (p. 882). Regardless of one’s personal feelings about the catholicity of the Reformation, it’s tough to deny that the Reformers themselves saw themselves as catholic.

Church tradition has a bad reputation among many Protestant groups. As discussed above, Barrett clarifies that the Reformers didn’t reject the authority of church tradition; they just saw it as a “ministerial authority” and not a "magisterial authority” equal to God’s written word (p. 415).

Barrett contrasts this ministerial authority with what he terms “biblicism,” the incorrect elevation of a “restrictive hermeneutical method onto the Bible” (p. 21). Biblicism is characterized by, among other things, the undervaluing of philosophy in a way that is “especially allergic to metaphysics,” overemphasis of human authorship, irresponsible proof texting that “fails to deduce doctrines from Scripture” (p. 21), and an ahistorical mindset that verges on C. S. Lewis’s “chronological snobbery.”

Biblicism is, in Barrett’s view, a mainstay of modern Protestant evangelical hermeneutics. But biblicist interpretation was also present in the Reformation: various groups followed the Reformers in rejecting Rome but did so in a way that split with mainstream Christian theology even more. To name just a few of the beliefs that the “radical Reformers” held:

These beliefs were all rejected by the mainstream Reformers, who as discussed above were uninterested in relitigating mainstream catholic doctrine. Instead, the Reformers took steps to educate people in proper Scriptural and theological understanding. In Geneva, Calvin worked to educate pastors and students in theology, Biblical languages, patristic and classical writings, and sound exegesis (even going so far as to found the Geneva Academy in 1559) (pp. 712–718). Unlike the anti-intellectual biblicism of the radical Reformers, the mainstream first- and second-generation Reformers believed in historically grounded scholarship.

I found this section particularly interesting because almost all of the beliefs advocated by the radical Reformers are still around today: free-grace theology is common, theonomian beliefs are gaining in popularity (as I mentioned in my review of Five Views on Law and Gospel), and separatist strategies remain appealing to certain Christian subgroups. It’s helpful to remember that the Reformers already considered—and rejected—these ideas in the 1500s.

Like many Protestants, Barrett sees the Council of Trent (1545–1563) as the moment where the Roman Catholic church went irreparably off the rails. Barrett emphasizes the internal dissent at Trent around issues like whether the Bible should be vernacular or in Latin (Cardinal Madruzzo opposed vernacular Scripture, while Cardinal Pacheco favored it; p. 856), whether the will was captive to sin as Luther claimed (Tommaso Sanfelice agreed but Dionisio de Zanettini disagreed; p. 858–859), and whether Scripture was superior to church tradition (Jacopo Nacchianti agreed with the Protestants that this was true; p. 855).

In the end, the Council of Trent took a decidedly anti-Protestant stance. In addition to cleaning up and reforming a lot of corruption and doctrinal chaos, the final decrees of Trent:

Trent also rejected any doctrine of sola fide, declaring that those who held such beliefs were latae sententiae (i.e. automatically) excommunicated. See Session 6, for instance:

If any one saith, that by faith alone the impious is justified; in such wise as to mean, that nothing else is required to co-operate in order to the obtaining the grace of Justification, and that it is not in any way necessary, that he be prepared and disposed by the movement of his own will; let him be anathema.

The Reformers responded by arguing that Trent itself contradicted the decrees of the historical church: Lutheran theologian Martin Chemnitz published Examination of the Council of Trent, while Calvin published Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent, with the Antidote (which e.g. calls Roman Catholics “those degenerate and bastard sons of the Roman See”).

Modern Protestant theologians agree. Barrett approvingly quotes Jaroslav Pelikan about the impact of Trent (p. 879, emphasis and ellipses original):

Trent seemed to Chemnitz to be condemning not only the Protestant principle of Luther’s Reformation, but considerable portions of the Catholic substance it purported to defend. For the weight of the Catholic tradition supported justification by grace alone without human merit, particularly if “Catholic tradition” included, as it did for Chemnitz, not merely learned theology, but also “all prayers of the saints in which they ask to be instructed, illumined, and sanctified by God. By these prayers they acknowledge that they cannot have what they are asking for by their own natural powers.” … Thus he demonstrated the truly traditional and Catholic character of the Reformation doctrine, implying that by closing the door to this doctrine Trent was making Rome a sect.

To Barrett, Trent is the moment when the “Roman Catholic” church broke once and for all with the true, catholic, and eternal church. Before Trent, it was possible that the Curia could change course to realign itself with the historical church; after Trent, schism was inevitable.

While popular Roman Catholic apologetics paints the Reformers as schismatics who shattered the eternal unity of the church (see the quotation from Belloc above), Barrett points out that the Reformation was just the latest in a long train of schisms that had already shattered the church.

The Orthodox churches had split from Rome in 1054, and the intervening centuries had seen repeated schisms/revolts against Roman-Catholic spiritual abuses that mostly ended in the brutal murders of the non-Roman parties (e.g. the Lollards, the Hussites, and the Waldensians). Seen thusly, the Reformation was just the last and most successful attempt by Christians to defy the increasingly authoritarian and ahistorical doctrines espoused by the Roman Curia—and efforts to put the blame of “schismatic” on the Reformers get the blame completely backwards.

(Roman Catholics will probably not appreciate this explanation.)

After all these details (and many more I haven’t bothered to summarize here), how well does Barrett’s thesis hold up? Following precedent from other fields, we can subdivide Barrett’s thesis into a “weak” claim & a “strong” claim and evaluate them separately.

The weak thesis of The Reformation as Renewal is that the Reformers saw themselves as more catholic than the Roman Catholics; in other words, that they saw themselves in community and continuity with the historical church, rather than “starting over” in a radical Biblicist way. Barrett defends this thesis with strong evidence—see section #4 above—and I think it’s tough to dispute his conclusion.

The strong thesis of The Reformation as Renewal is that the Reformers were right to believe this. This is significantly harder to prove; even Barrett has to concede that Luther has some significant points of disagreement with the likes of Anselm and Peter Lombard, and it’s tough for me to judge whether these disagreements are more or less substantial than the analogous differences that the 1500s-era Roman Catholic church might have had.

It’s difficult to escape the conclusion that the Reformation did represent a significant change in theology and Christian practice—but not an absolute change—and I find Barrett’s efforts to minimize this point misleading.

As astute readers may have surmised, Barrett is not interested in writing a neutral or objective history of the Reformation—he has an axe to grind, and he makes his points early and often. Accordingly, Roman Catholics are unlikely to enjoy or be convinced by this book; Barrett has no patience for Rome or its doctrines and misses no opportunity to attack it. A less pugnacious book would probably be more ecumenical, but that’s not Barrett’s aim.

Instead, Barrett is writing for his fellow Protestants. The Reformation As Renewal makes a strong case that Protestants should take church history seriously and hesitate to dismiss millennia of thought and tradition. Figures like John Chrysostom, Maximus the Confessor, and Gregory the Great (whom Calvin called “the last good pope”) aren’t just part of the Catholic spiritual heritage; the Reformers viewed these figures as their spiritual ancestors and, Barrett claims, so should we.

Despite my high-level qualms, I think the book is effective towards this end. Most Protestants are consciously or subconsciously comfortable with ignoring anything that happened between c. 400 and 1517. Many extend this even to the Reformers: as one early reader said: “Why should I care about what Luther said about something?" Faced with a confusing morass of historical and theological terms, it’s tempting for modern Protestants to simply discard all previous Biblical interpretation and start ex nihilo, one church at a time.

Barrett’s rhetoric works well when he combats this impulse. By examining in exhaustive detail how the Reformers interacted with their own predecessors, The Reformation as Renewal shows how Protestants can balance sola scriptura with church tradition. Luther didn’t accept what Ockham, Aquinas, or even Augustine said as binding—but he read and understood their thinking before striking out on his own, much as earlier church fathers had been in dialogue (and disagreement) with each other. Barrett’s account demonstrates that Protestantism doesn’t necessitate biblicism, despite modern tendencies.

One might reasonably ask, though, “so what”? If Protestants accept that they’re part of the rich intellectual tradition of the historical church and start reading catechisms, creeds, & patristic writings, what do we expect to change? What’s the practical consequence of viewing the Reformation as renewal, aside from antagonizing our friendly neighborhood Roman Catholics?

For Barrett, the answer to this question appears to be “reject congregationalism & adult baptism and become Anglican.” Barrett made waves in Christian circles last year when he renounced Southern Baptism and announced that he was joining the Anglican church. You can read his statement here; I don’t find his reasons very compelling and neither do Baptists.

(In one of ChatGPT’s funnier moments as an editor for this post, it asked whether Barrett’s writing was “smuggling in Anglican ecclesiology under cover of patristic appreciation.” A fair question!)

More generally, modern low-church Protestantism often suffers from the problem of the superstar founder–pastor who’s singlehandedly responsible for the entire church’s theology, teaching, and operations. This leaves churches susceptible to the whims of a single person’s decisionmaking, with predictable consequences. While “caring about history” won’t by itself fix the weird culture and incentives of the 21st-century church, one can imagine that more historically grounded churches might be less reliant on a single individual and more resilient.

More broadly, though, Barrett’s book reminds me that ideas matter. We live in a nominalist age, where people are quick to disregard the importance of metaphysics and universals (e.g.). When reading about debates like “whether Christ has one energy or two energies in the hypostatic union”, it’s tempting to just say “who cares?” and dismiss the whole debate as irrelevant & pointless.

(I complained about this in last year’s review of The New Roman Empire—it’s impossible to study Byzantine history without understanding various Church councils and theological debates, yet Kaldellis writes his history from a dialectical–materialist perspective that basically discounts theology altogether.)

Barrett’s book brings me back to a world in which theological ideas were seen as of first importance, to the extent that thousands of people were willing to die for them (and did). While I don’t hope for a return of the French Wars of Religion, I think Barrett’s book is a useful antidote to the theological nihilism of the modern church.

I’ll close with this famous quotation from Machiavelli, which more than anything else captured my experience reading The Reformation As Renewal:

When evening comes, I return home and go into my study. On the threshold I strip off my muddy, sweaty, workday clothes, and put on the robes of court and palace, and in this graver dress I enter the antique courts of the ancients and am welcomed by them, and there I taste the food that alone is mine, and for which I was born. And there I make bold to speak to them and ask the motives of their actions, and they, in their humanity, reply to me. And for the space of four hours I forget the world, remember no vexation, fear poverty no more, tremble no more at death: I pass indeed into their world.

For weeks I would come home from my job, make dinner, play with my kids, put them to bed, and then open this 900-page tome and, for a few hours, lose myself in the intellectual world of medieval Europe, full of debates about analogical & univocal predication and similarly foreign concepts to the modern mind. If you too want this experience, then The Reformation As Renewal is the book for you.

Thanks to the friends and early editors who helped me attempt to make sense of these ideas. As usual, any errors are mine alone.