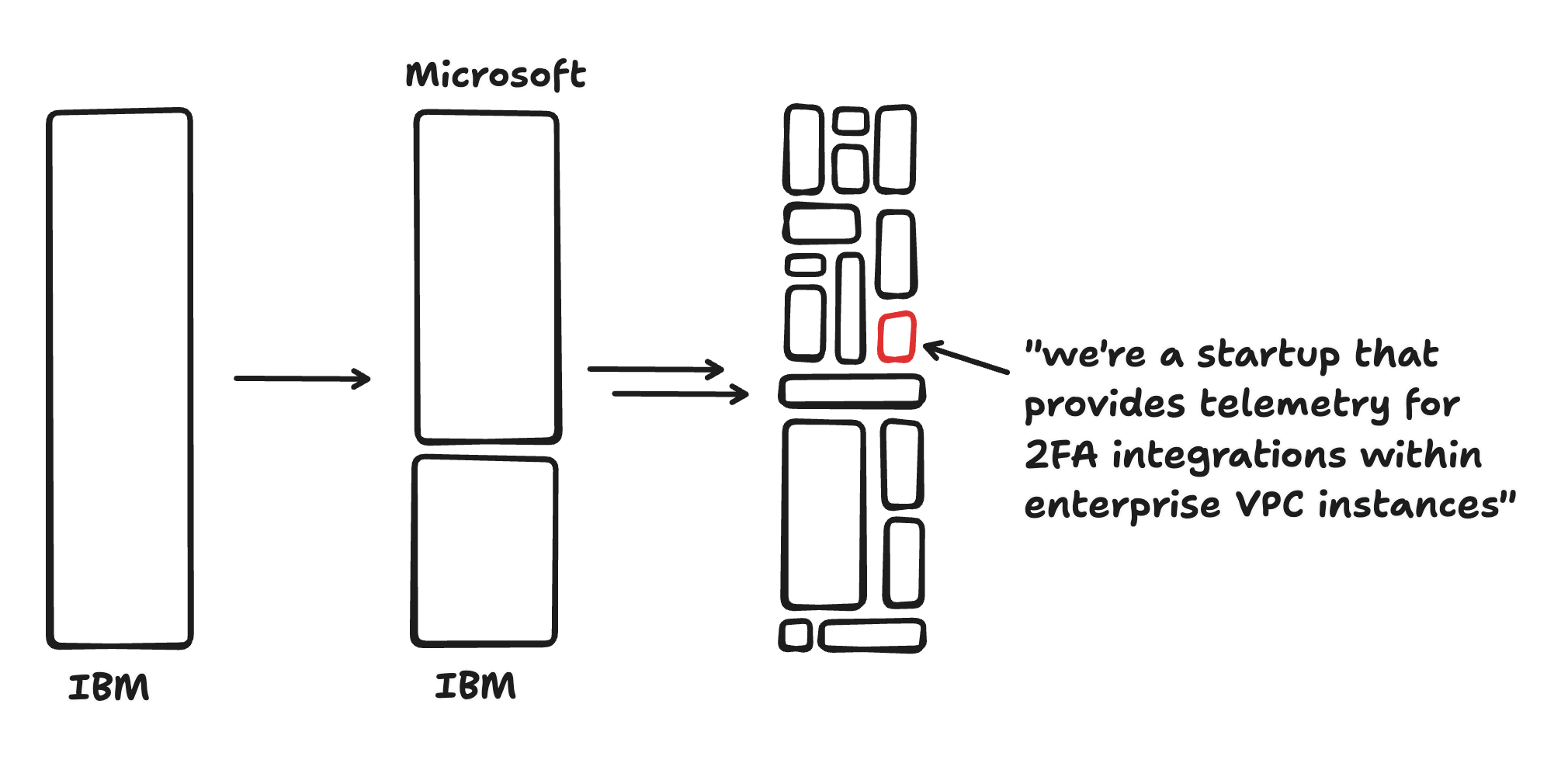

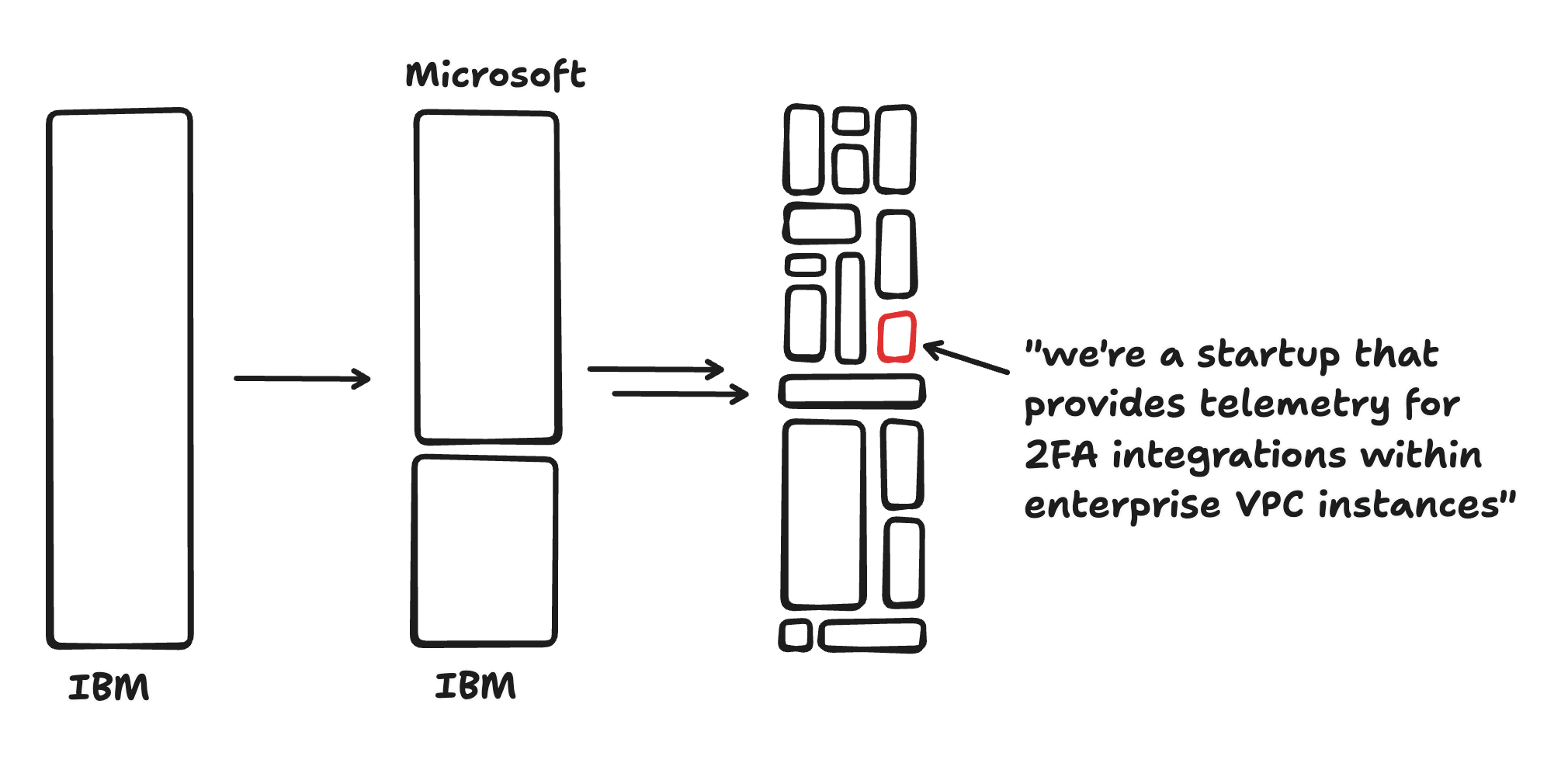

Long ago, there were no software companies. In the age of System/360, vertically integrated companies like IBM were responsible for virtually all aspects of the end product they sold, from hardware to operating system to end-user applications. Then, the value chain started to diversify: Microsoft allowed software and hardware to become decoupled, and then a variety of application-specific companies started to pop up (like Lotus). Today the software ecosystem is incredibly diverse, and even simple software companies typically rely on a web of vendors and sub-vendors.

I call this process “horizonalization,” because it reflects a move from vertically integrated monoliths towards an ecosystem of companies aimed at horizontally integrating a given capability:

We can imagine two reasons why this transformation might have happened:

Ronald Coase’s 1937 paper “The Nature of the Firm” proposes a theoretical framework that will be useful for this discussion. Coase argues that the natural size of companies is an equilibrium between competing factors. Making companies bigger makes work easier by diminishing “transaction costs”: doing work with external parties requires coordination, NDAs, invoices, taxes, and so on, while doing work with someone inside the same company is comparatively easy. Unfortunately, larger companies also become less efficient, because “the entrepreneur fails to place the factors of production in the uses where their value is greatest” (pp. 394–395), i.e. managers do a bad job. So in practice these opposing forces balance and companies end up at a size somewhere between “everyone is their own company” and “there’s only one company.”

Viewed this way, horizontalization is a natural response to increasing market size and complexity. As the market became big enough that there could be “a database company” or “an ads company,” it became advantageous for these capabilities to become their own firms rather than stay part of a single monolithic ur-company. These same firms, once independent, were able to innovate and find new markets and technologies more rapidly than they could have before, further growing the sector and continuing the process.

As readers may have inferred from the title, I think the same transformation is happening in biotech and drug discovery today. Fifty years ago, drug discovery was almost entirely vertically integrated. New biotech companies had to rebuild almost every capability themselves from scratch (The Billion-Dollar Molecule documents Vertex doing this in the 1980s).

In the 2000s and 2010s “virtual biotech” companies that outsourced most or all of the chemistry and biology work to CROs and CDMOs became common—see this 2012 article from Derek Lowe, which discusses the change in the industry. These virtual biotechs often had no aspiration to be around forever; many single-asset virtual biotechs aimed to pursue a given biological target through early-stage clinical trials and then get bought by pharmaceutical companies, who would fund Phase III trials and subsequent manufacturing & distribution.

Not coincidentally, this time period also saw CROs and software companies like Schrodinger and Benchling become important ecosystem vendors. As the expected life cycle of therapeutics companies decreased, it became important to conserve cash and not build out unnecessary infrastructure that wouldn’t pay for itself within a few years. Increasing amounts of research started to be done through research-as-a-service models, and the burden of building efficient high-throughput research processes shifted away from internal teams and towards vendors. Basically, the pendulum moved away from “build” and towards “buy.”

Today, I think this trend is continuing or even accelerating. Here’s a few case studies:

Despite these examples, horizontalization is harder in biotech than in software. Broadly, transaction costs are higher—pre-clinical IP is very sensitive, making companies more suspicious of outside vendors—meaning that it’s harder to partner externally and easier to bring capabilities in-house. The total biotech market is also smaller, meaning that there are fewer potential customers for any new vendor and thus fewer possible niches.

But the growing complexity of drug discovery in the era of AI and lab automation counteracts these trends somewhat, because all this complexity can only be managed by outsourcing capabilities to vendors. Imagine trying to build the equivalent of the OnePot self-driving lab within every new oncology startup! Every new layer of complexity creates opportunities for vendors to decrease unit costs by increasing upfront capital expenditure; scale economies create the incentives for horizontalization.

I think that horizontalization is good for the world. One reason is just that horizontalization creates efficiency—this is a pretty obvious point, going back all the way to Adam Smith, but it still needs to be said. Companies that specialize in a given technology, service, or product can typically do a better job than a team trying to add yet another random capability. That’s why Plasmidsaurus is better at sequencing things than you are.

But horizontalization also increases the field’s institutional memory. Early-stage biotech has weird company dynamics—as discussed above, most therapeutics companies survive only a handful of years, ending their existence either through acquisition or quiet dissolution. (In many cases the preclinical research team disbands even if the legal entity technically survives.) This means that there’s a lot of tacit institutional knowledge which gets lost or dispersed. A DNA-encoded library team might have developed a set of protocols, workflows, and practices which led to incredible performance, but if their company lays off all the research staff, then all this has to be recreated de novo wherever these scientists work next.

Coupled with the atmosphere of secrecy in the industry, the overall effect is that best practices are slow to diffuse in early-stage drug discovery. Horizontalization provides an opportunity to fix this. To use the specific example of DNA-encoded libraries (DELs) again, companies like Om and Leash can develop DEL-related expertise that far exceeds what any single therapeutics can achieve, and keep this knowledge and “process power” alive longer than the typical lifespan of a therapeutics company.

If horizontalization is happening, and will happen more in the future, what are the consequences? Here’s some speculation:

1. There are more viable biotech-adjacent businesses than people think. Each new biotech-adjacent company that gets created becomes a new potential customer for another vendor, increasing total market liquidity and creating new opportunities for innovation. It’s not quite clear how far these trends will go, but I think the prevailing VC sentiment that “the only way to monetize biotech innovation is through therapeutic assets” is already wrong.

2. Transaction costs will matter more. Right now, it’s pretty easy to start using a different software vendor (just sign up and point your code at the right API endpoint) but relatively difficult to start working with a new vendor in biotech. There are good reasons for this. As discussed above, drug discovery is a very IP-sensitive industry, and the wrong chemical structure in the wrong hands might cost millions or even billions of dollars.

Rejecting all external vendors and internalizing every function can’t be the right answer, as increasing complexity will make monoliths less and less capable over time. Instead, the industry needs to find ways to lower transaction costs without compromising on IP or security. The company that figures this out will be a big winner.

Both of these predictions might be wrong! But, at a high level, I think horizontalization is both inevitable and beneficial; I look forward to the day when biotech has as many interesting and competent vendors as software, and I’m working to try and make Rowan one of those vendors.

Thanks to Ari Wagen for helpful conversations on these topics and for editing drafts of this essay.