In center-right tech-adjacent circles, it’s common to reference René Girard. This is in part owing to the influence of Girard’s student Peter Thiel. Thiel is one of the undisputed titans of Silicon Valley—founder of PayPal, Palantir, and Founders Fund; early investor and board member at Facebook; creator of the Thiel Fellowship; and mentor to J.D. Vance—and his intellectual influence has pushed Girard’s ideas into mainstream technology discourse. (One of Thiel’s few published writings is “The Straussian Moment,” a 2007 essay which explores the ideas of Girard and Leo Strauss in the wake of 9/11.)

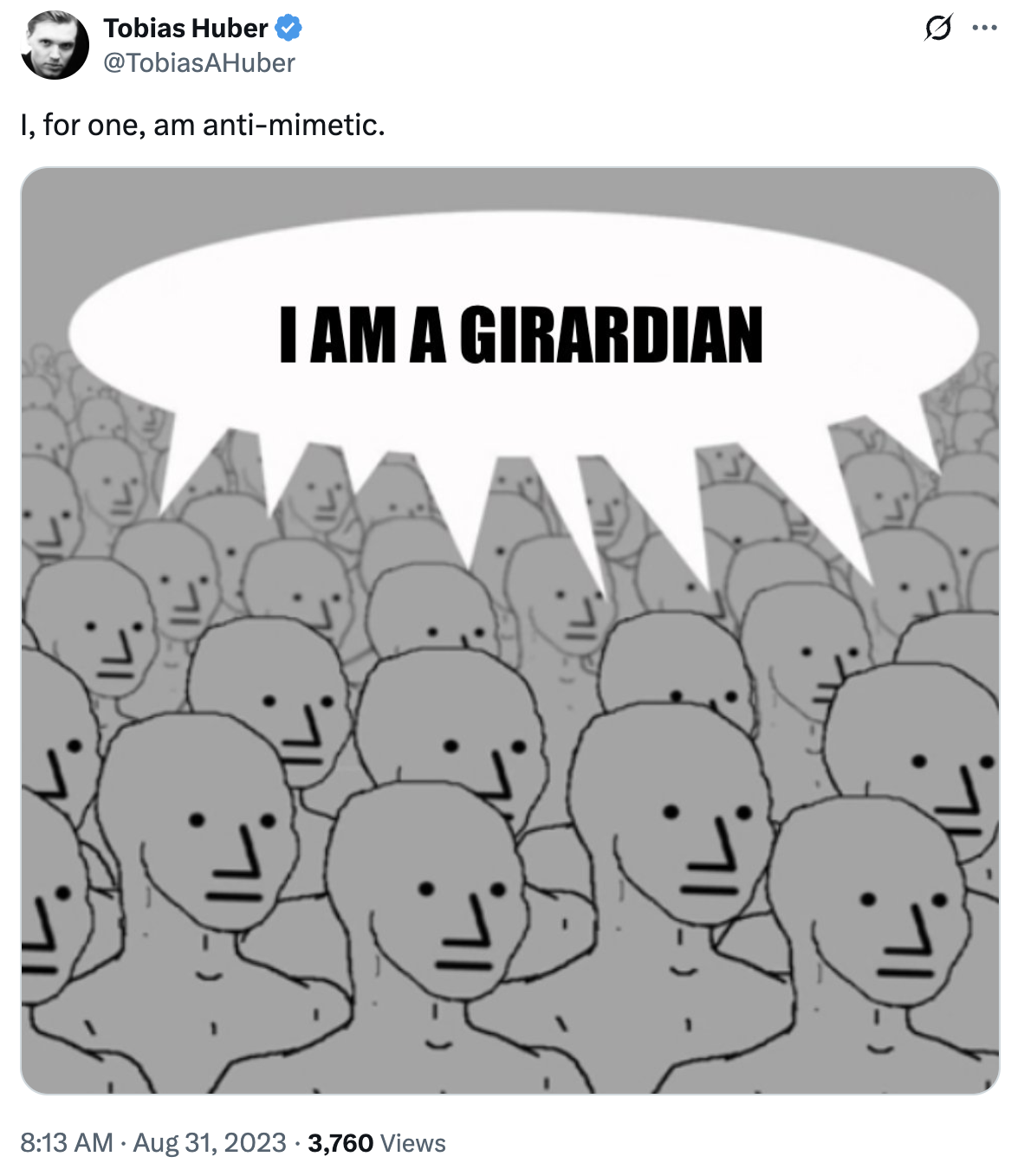

As a chemistry grad student exploring startup culture, I remember going to events and being confused why everyone kept describing things as “Girardian.” In part this is because Girard’s ideas are confusing. But the intrinsic confusingness of Girard is amplified by the fact that almost no one has actually read any of Girard’s writings. Instead, people learn what it means to be “Girardian” by listening to the term in conversation or on a podcast and, with practice, learn to start using it themselves.1

I’ve been in the startup scene for a few years now, so I figured it was time I read some Girard myself rather than (1) avoiding any discussions about Girard or (2) blindly imitating how everyone else uses the word “Girardian” and hoping nobody finds out. What follows is a brief review of Girard’s 2001 book I See Satan Fall Like Lightning and an introduction to the ideas contained within, with the caveat that I’m not a Girard expert and I’ve only read this one book. (I’ve presented the ideas in a slightly different order than Girard does because they made more sense to me this way; apologies if this upsets any true Girardians out there!)

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning opens with a discussion of the 10th Commandment:

You shall not covet your neighbor's house; you shall not covet your neighbor's wife, or his male servant, or his female servant, or his ox, or his donkey, or anything that is your neighbor's. (Ex 20:17, ESV)

Girard argues that the archaic word “covet” is misleading and that a better translation is simply “desire.” This commandment, to Girard, illustrates a fundamental truth of human nature—we desire what others have, not out of an intrinsic need but simply because others have them. This is why the 10th Commandment begins by enumerating a list of objects but closes with a prohibition on desiring “anything that is your neighbor’s.” The neighbor is the source of the desire, not the object.

The essential and distinguishing characteristic of humans, in Girard’s framing, is the ability to have flexible and changing desires. Animals have static desires—food, sex, and so on—but humans have the capacity for “mimetic desire,” or learning to copy another’s desire. This is both good and bad:

Once their natural needs are satisfied, humans desire intensely, but they don’t know exactly what they desire, for no instinct guides them. We do not each have our own desire, one really our own… Mimetic desire enables us to escape from the animal realm. It is responsible for the best and the worst in us, for what lowers us below the animal level as well as what elevates us above it. Our unending discords are the ransom of our freedom. (pp. 15–16)

Mimetic desire leads us to copy others’ desires: we see that our friend has a house and we learn that this house is desirable. Mimetic desire, however, leads us into conflict with our neighbor. The house that we desire is the one that someone already has; the partner we desire is someone else’s.

To make matters worse, our own desire for what our neighbor validates and intensifies their own desire through the same mechanism, leading to a cycle of “mimetic escalation” in which the conflict between two parties increases without end. The essential sameness of the two parties makes violence inescapable. The Montagues and Capulets are two noble houses “both alike in dignity” (Romeo and Juliet, prologue)—their similarity makes them mimetic doubles, doomed to destruction.

While the above discussion focuses only on two parties, Girard then extends the logic to whole communities, arguing that unchecked mimetic desire would lead to the total destruction of society. To prevent this, something surprising happens: the undirected violence that humans feel towards their neighbors is reoriented onto a single individual, who is then brutally murdered in a collective ritual that cleanses the society of its mutual anger and restores order. Here’s Girard again:

The condensation of all the separated scandals into a single scandal is the paroxysm of a process that begins with mimetic desire and its rivalries. These rivalries, as they multiply, create a mimetic crisis, the war of all against all. The resulting violence of all against all would finally annihilate the community if it were not transformed, in the end, into a war of all against one, thanks to which the unity of the community is reestablished. (p. 24, emphasis original)

(Note that the word “scandal” here is Girard’s transliteration of the Greek σκάνδαλον, meaning “something that causes one to sin” and not the contemporary and more frivolous meaning of the word.)

This process is called the “single-victim mechanism”; the victim is chosen more or less at random as a Schelling point for society’s anger and frustration, not because of any actual guilt. Girard recognizes that this process seems foreign to modern audiences and mounts a vigorous historical defense of its validity. He recounts an episode from Philostratus’s Life of Apollonius of Tyana (link) in which Apollonius ends a plague in Ephesus by convincing the crowd to stone a beggar. Philostratus explains this by saying that the beggar was actually a demon in disguise, but Girard argues that the collective violence cures the Ephesians from social disorder, and that the victim is retrospectively demonized (literally) as a way for the Ephesians to justify their actions.

(How does ending social disorder cure a plague? Girard argues that our use of “plague” to specifically mean an outbreak of infectious disease is anachronistic, and that ancient writers didn’t differentiate between biological and social contagion—in this case, the plague must have been one of social disorder, not a literal viral or bacterial outbreak.)

While we no longer openly kill outsiders to battle plagues, Girard argues that the violent impulses of the single-victim mechanism are still visible in modern societies: he uses the examples of lynch mobs, the Dreyfus affair, witch hunts, and violence against “Jews, lepers, foreigners, the disabled, the marginal people of every kind” (p. 72) to illustrate our propensity towards collective violence. Racism, sexism, ableism, and religious persecution are all different aspects of what Girard argues is a fundamental urge towards collective majority violence.

In the past, ritual human sacrifice is well-documented: see inter alia the Athenian pharmakoi, the Mayan custom of throwing victims into cenotes to drown, and the sinister rites of ancient Celts. While modern anthropologists are typically perplexed by these rituals, Girard argues that they ought not to be downplayed. The development of the single-victim mechanism across so many cultures is not an accident. Instead, this mechanism is the foundation of all human culture, because it replaces primitive violence (which leads to anarchy) with ritual violence and allows society to persist and create institutions.

The single-victim mechanism is necessary cultural technology, which is why so many cultures share the myth of a “founding murder” (Abel, Remus, Apsu, Tammuz, and so on). But the founding murder doesn’t just herald the creation of human society. The collective murder of the victim does so much to restore harmony to the community that the transformation seems miraculous. The people, having witnessed a miracle, decide that the one they killed must now be divine:

Unanimous violence has reconciled the community and the reconciling power is attributed to the victim, who is already “guilty,” already “responsible” for the crisis. The victim is thus transfigured twice: the first time in a negative, evil fashion; the second time in a positive, beneficial fashion. Everyone thought that this victim had perished, but it turns out he or she must be alive since this very one reconstructs the community immediately after destroying it. He or she is clearly immortal and thus divine. (pp. 65–66)

This might seem bizarre—it did to me when I read it—but many other writers have discussed the peculiar motif of the “dying then rising” deity. A more historical example is Caesar, who is first killed and then deified as the founder of the Roman Empire, with his murder being the central event in the advent of the new age.

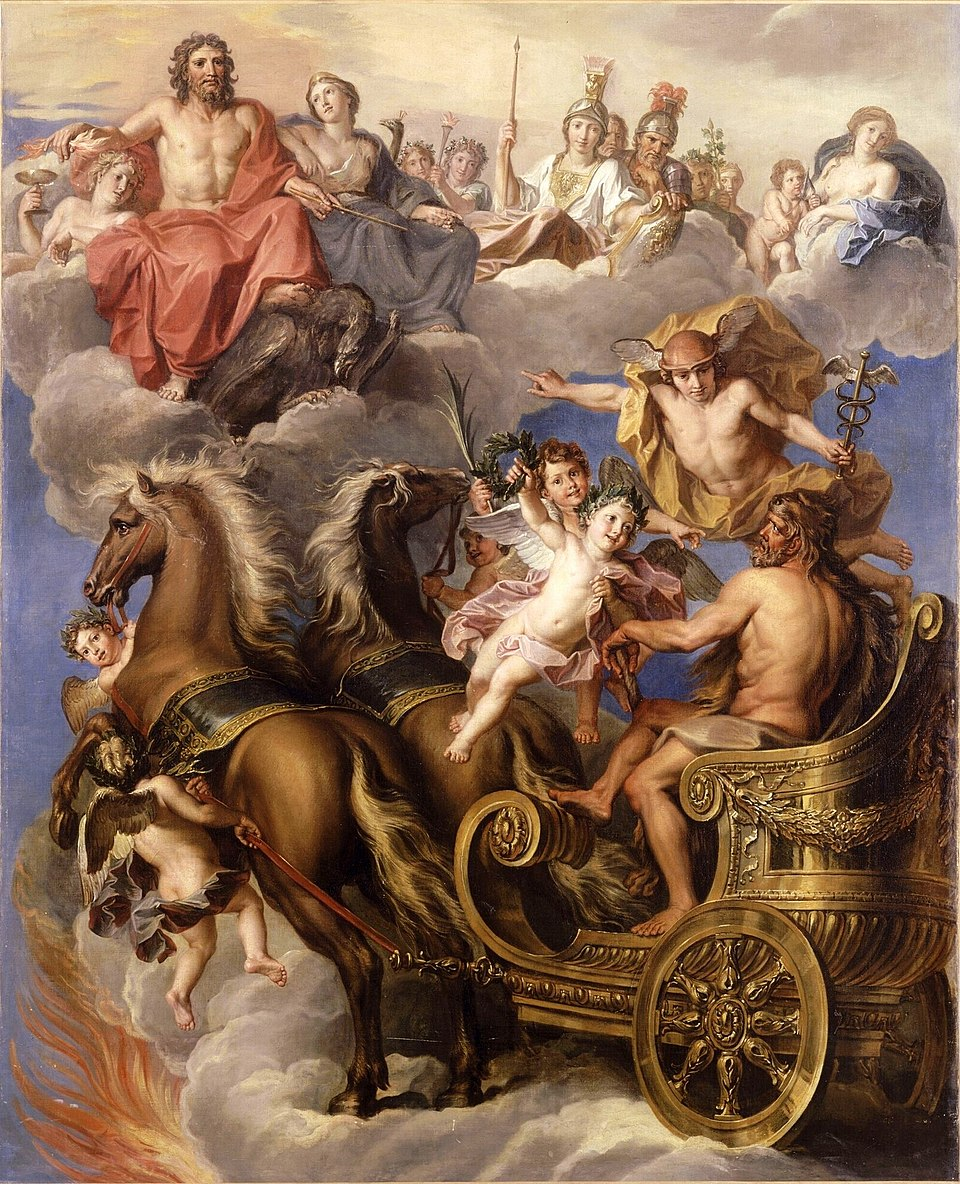

Pagan myths and deities, Girard argues, are the echoes of a shadowy pre-Christian era of violent catharsis, a time in which “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must” (Thucydides). Behind the sanitized modern stories of Mount Olympus and Valhalla—dark even in their original, non-Percy-Jackson retellings—are sinister records of outcasts who were first killed and then deified.

Girard argues that the Bible stands in opposition to this mimetic cycle. Collective violence threatens figures like Joseph, Job, and John the Baptist, but the Biblical narrative both defends their innocence and maintains their humanity. The Psalms repeatedly defend the innocence of the Psalmist against the unjust accusation of crowds (cf. Psalms 22, 35, 69). Uniquely among ancient documents, the Bible takes the side of the victim and not the crowd.

In the Gospels, Jesus opposes the single-victim mechanism. In the story of the woman convicted of adultery, he tells the accusers “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her” (John 8:7, ESV). This is the exact opposite of Apollonius of Tyana:

Saving the adulterous woman from being stoned, as Jesus does, means that he prevents the violent contagion from getting started. Another contagion in the reverse direction is set off, however, a contagion of nonviolence. From the moment the first individual gives up stoning the adulterous woman, he becomes a model who is imitated more and more until finally all the group, guided by Jesus, abandons its plan to stone the woman. (p. 57)

(Unfortunately, it’s unlikely that the story of the woman accused of adultery is in the original text of John. The oldest New Testament sources we have, like Codex Vaticanus, Codex Sinaiticus, and various papyri, lack this story.)

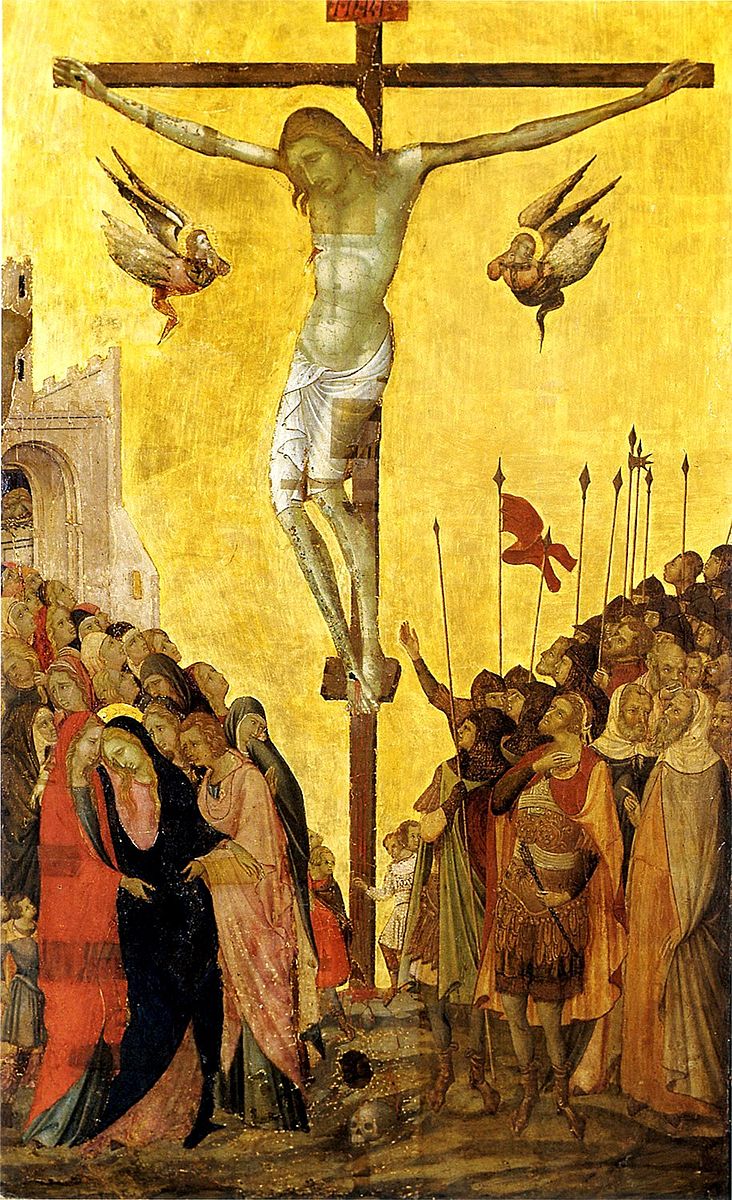

Jesus becomes the target of mimetic violence himself, of course, culminating in his crucifixion and death at Calvary. But Girard argues that what seems like the ultimate victory of mimetic violence—the brutal murder of the person who sought to stop it—is actually its moment of defeat, what he calls the “triumph of the cross” in a paraphrase of Colossians 2. He writes:

The principle of illusion or victim mechanism cannot appear in broad daylight without losing its structuring power. In order to be effective, it demands the ignorance of persecutors who “do not know what they are doing.” It demands the darkness of Satan to function adequately. (pp. 147–148)

Unlike in previous cases, where the actions of the crowd were unanimous and the victim perished alone, a minority remains to proclaim the innocence of Jesus. While the majority of the crowd doesn’t follow them, this is enough—the collective violence of the crowd can only function properly as long as the crowd remains ignorant of what they’re doing. Clearly explaining the victim mechanism also serves to destroy it, and so the victim mechanism is ended by the testimony of the early Christians, a stone “cut out by no human hand” that grows to fill the whole world and destroys the opposing kingdoms (Daniel 2:34–35, ESV).

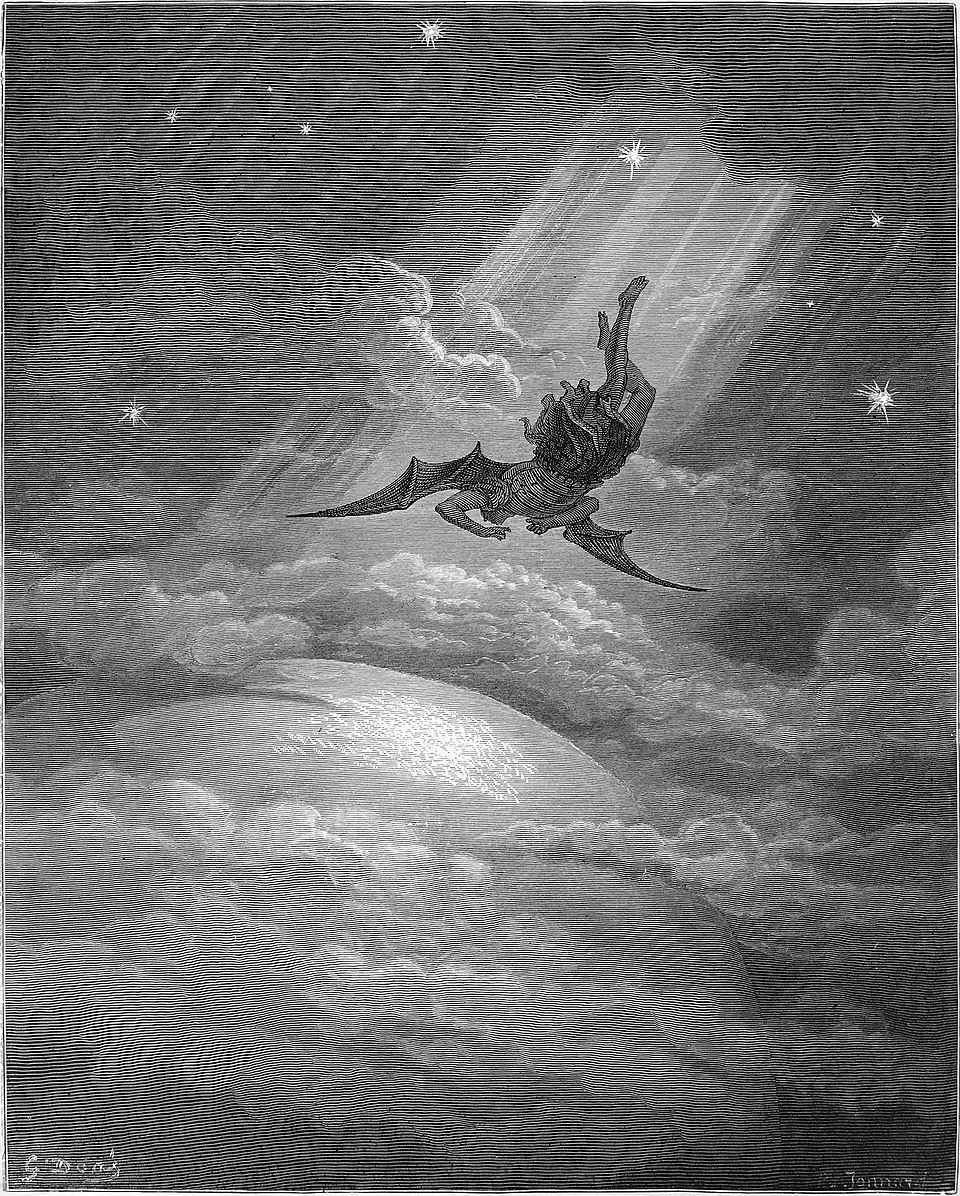

The Gospel narrative exposes the workings of the victim mechanism and defeats it. While Satan thinks he’s winning by killing Jesus, Jesus’ death will make the single-victim mechanism clear and destroy the ignorance in which the Prince of Darkness must work. Girard explains this as the theological idea of “Satan duped by the cross” (which modern listeners may recognize from The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe):

God in his wisdom had foreseen since the beginning that the victim mechanism would be reversed like a glove, exposed, placed in the open, stripped naked, and dismantled in the Gospel Passion texts… In triggering the victim mechanism against Jesus, Satan believed he was protecting his kingdom, defending his possession, not realizing that, in fact, he was doing the very opposite. (p. 151)

While the story of Jesus’s resurrection might seem to have many parallels with the divinization of sacrificial victims, Girard says that these are “externally similar but radically opposed” (p. 131). Indeed, he argues that the Gospel writers intentionally highlighted similarities between the false resurrection of collective violence and the true resurrection of Jesus: Mark 6:16 shows Herod anxious that John the Baptist, whom he killed, has come back to life, while Luke 23:12 shows how Jesus’ death makes Herod and Pilate friends in the same way the victim mechanism always does. In Girard’s words, “the two writers emphasize these resemblances in order to show the points where the satanic imitations of the truth are most impressive and yet ineffectual” (p. 135). The divinization of victims is pathetic and flimsy next to the true resurrection.

In the new Christian age, Jesus invites us to avoid mimetic contagion not by attempting to avoid having desires in a Buddhist way—to do so is to deny our nature as humans—but by presenting himself as the model for humans to imitate. Only Jesus, the Bible argues, is a fitting template for human desire: hence Paul’s command to “imitate me as I imitate Christ” (1 Cor 11:1), and the consistent call throughout Scripture to love what God loves and hate what God hates (cf. Ps. 139).

Girard ends his book with a discussion of modernity and our culture’s now-total embrace of victims. Girard’s writing is powerful, concise, and difficult to summarize in this section, so I’ll quote from the final pages at length.

All through the twentieth century, the most powerful mimetic force was never Nazism and related ideologies, all those that openly opposed the concern for victims and that readily acknowledged its Judeo-Christian origin. The most powerful anti-Christian movement is the one that takes over and “radicalizes” the concern for victims in order to paganize it. The powers and principalities want to be “revolutionary” now, and they reproach Christianity for not defending victims with enough ardor. In Christian history they see nothing but persecutions, acts of oppression, inquisitions.

This other totalitarianism presents itself as the liberator of humanity. In trying to usurp the place of Christ, the powers imitate him in the way a mimetic rival imitates his model in order to defeat him. They denounce the Christian concern for victims as hypocritical and a pale imitation of the authentic crusade against oppression and persecution for which they would carry the banner themselves.

In the symbolic language of the New Testament, we would say that in our world Satan, trying to make a new start and gain new triumphs, borrows the language of victims. Satan imitates Christ better and better and pretends to surpass him. This imitation by the usurper has long been present in the Christianized world, but it has increased enormously in our time. The New Testament evokes this process in the language of the Antichrist…

The Antichrist boasts of bringing to human beings the peace and tolerance that Christianity promised but has failed to deliver. Actually, what the radicalization of contemporary victimology produces is a return to all sorts of pagan practices: abortion, euthanasia, sexual undifferentiation, Roman circus games galore but without real victims, etc.

Neo-paganism would like to turn the Ten Commandments and all of Judeo-Christian morality into some alleged intolerable violence, and indeed its primary objective is their complete abolition. (pp. 180–181, emphasis original)

Satan, whose previous work through the victim mechanism was defeated by Christianity, now seeks to imitate God’s people and use their own arguments against them. Although Christians invented the idea of having sympathy for the victim (in Girard’s view), Satan now argues that Christianity itself is intrinsically a form of violence against victims, with the only solution being the “complete abolition” of Christian morals. Girard alleges that this is bad, and if implemented would lead to the pagan anarchy of long ago.

Girard’s style is hard to pin down: he bounces between anthropology, close reading of ancient texts, history, and theology without breaking stride. I enjoy reading his writing a lot, but sometimes I wish there would be more sources: he alludes to a fascinating series of historical interviews with tribes that practiced human sacrifice, for instance, but doesn’t leave a reference to the original interviews.

As a work of theology, I See Satan Fall Like Lightning is interesting but peculiar. It’s not clear to me how interested Girard is in orthodox Christian thought. He alternates between referring to Satan as a person and an abstract concept, for instance, and uses few ideas that would be familiar to students of mainstream systematic theology. This isn’t necessarily wrong, but leaves me with a lot of open questions: what does Girard make of the sacrifice of Isaac, or the concept of sanctification, or the role of faith in all this? These might be answered in his other writings, but they weren’t answered here.

As a work of history, I See Satan Fall Like Lightning is downright bizarre. The book’s literal claim—that all non-Christian “gods” are deified victims of ritual mass murder—is hard for me to accept at face value. That being said, it’s hard enough to reason about the recent past, let alone ancient pre-history. Maybe he’s right about all this? Evidence feels scarce, though, and I See Satan Fall Like Lightning hardly conducts a careful meta-analysis of all available ancient myths.

Perhaps the most similar work to Girard’s in scope and ambition is Julian Jaynes’s The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind (Wikipedia, Slate Star Codex).2 Jaynes argues that ancient people didn’t actually have theory of mind or a concept of the self: instead, they personified their internal monologue and viewed it as the voice of the gods. We usually don’t notice this when we read ancient texts, because we subconsciously assume that they were similar to us. But, to quote Scott’s review:

Every ancient text is in complete agreement that everyone in society heard the gods’ voices very often and usually based decisions off of them. Jaynes is just the only guy who takes this seriously.

Much like Jaynes, Girard takes a surprising historical observation—the ubiquity of human sacrifice and the fact that ancient people saw this as essential to the health of their society—and takes it seriously, building an entire argument about how ritual human sacrifice is the original cultural technology and the root of all civilization. While I’m not fully convinced, the intellectual commitment is admirable.

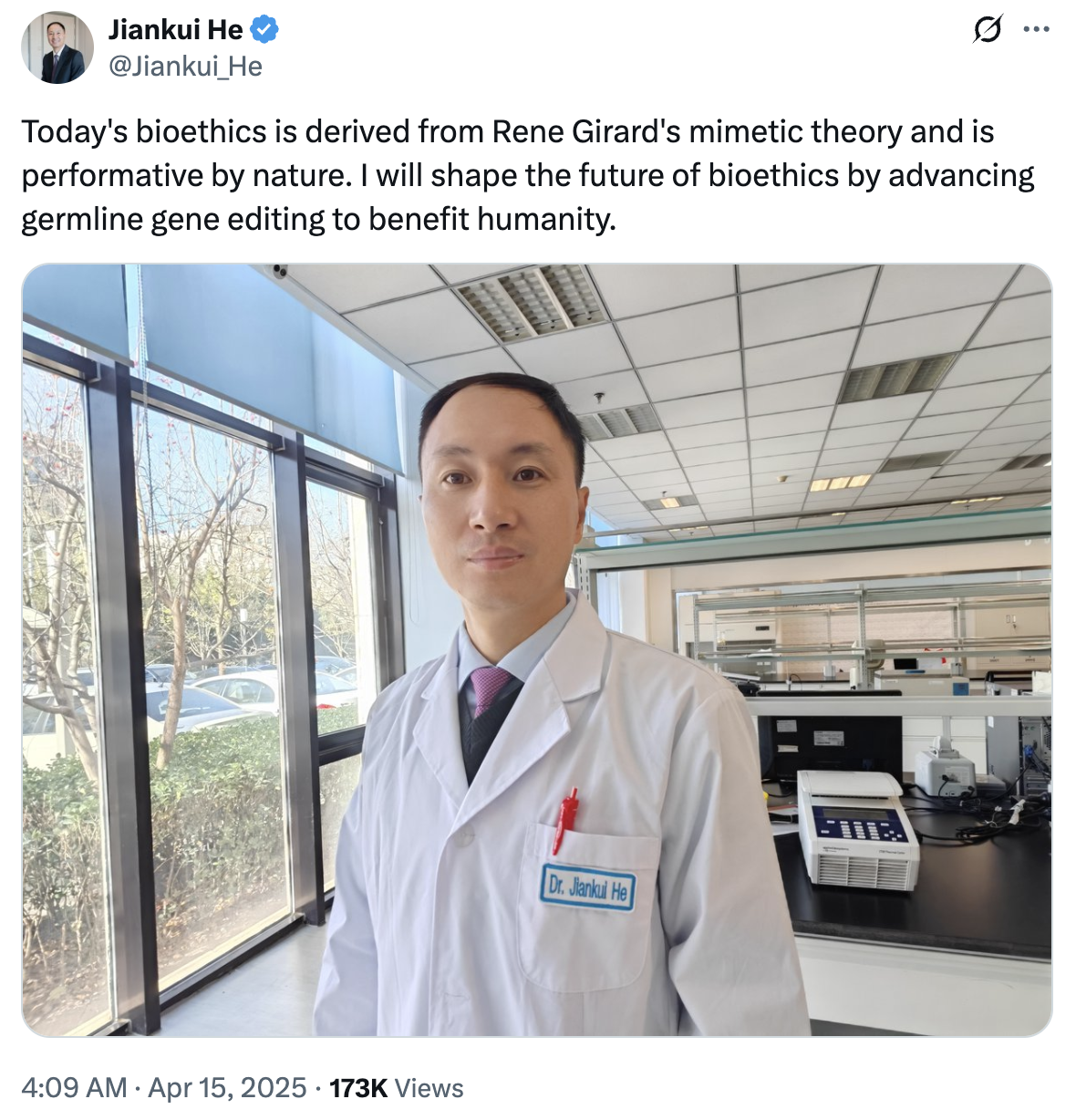

Most bizarre of all, though, is the fact that these esoteric ideas have become a mainstream part of “Grey Tribe” thought. If I’d read this book in a vacuum, I wouldn’t expect that any of the ideas would have achieved much popularity—but in today’s world, describing things as “Girardian” or “mimetic” is de rigueur for the aspiring thought leader.

This observation itself is perhaps the best testimony to the strength of Girard’s ideas. What force other than mimetic rivalry could be strong enough to convince thousands of venture capitalists, each attempting to craft a contrarian high-conviction persona, to all reference the same Christian philosophical anthropologist?