(This post is copied from some notes I gave to our summer interns at Rowan almost without modification. Hopefully people outside Rowan find this useful too!)

This is a brief and opinionated guide on how to give a research talk to an external audience. Some initial points of clarification—this guide is for a research talk, not a sales call or a VC pitch. Research talks have their own culture and norms; treating a research talk as a sales call is likely to backfire disastrously.

When is a research talk appropriate? Generally, if you’re talking to scientists, you should view your talk as a research talk, unless specifically advertised otherwise.

This advice is not directly applicable for talks to internal audiences; collaborators need much less context than external audiences and you can streamline your talk accordingly. (Note that “external” and “internal” here refer to projects, not corporations—a talk to a different division of your company is “external” to the project even if you technically have the same employer.)

The goal of an external research talk is to teach the audience something. This is generally underappreciated. Many people act as if the goal of the talk is to show that they’re smart, or to show how impressive their research is, or to dump all the data from a given paper onto slides. All of these lead to talks that are mediocre at best and barbarous at worst.

If you learn something from a talk, it’s a good talk. This is also nice because it’s easy to learn something; even bad results can teach you something. For talks in different fields, I often learn more from the introduction to a talk than from the actual results section (which goes over my head).

In any given talk, there might be several categories of people.

A perfect talk has something for everyone; you can give the fans something they didn’t read in the paper, mollify the critics, teach most listeners something new, and maybe even interest the clueless folks.

My contrarian take is that the background/history should comprise 30–40% of the talk. Most people have less context for your work than you expect; “context is that which is scarce.” It’s almost always worth spending more time explaining why what you’re doing is important, what other people have done, and how people in your field think about problems.

Paradoxically, the longer you spend on background, the more impactful your results might be. You’re both building tension, as the audience wonders when you’ll get to your research, and you’re positioning your research such that when you share your actual idea the audience will be maximally excited. (I always picture this like an old-school samurai duel; the longer you wait before you “strike” with your results, the better.)

Many scientists overemphasize discussing their implementation and results. These topics are always the focus of the actual work, because they take the bulk of the time, and papers focus on these too since they require the most details and associated data. But talks that just explain mathematics, statistics, or data cleaning in detail are usually boring or painful to listen to—just because you suffered through the details of this process doesn’t mean the audience needs to suffer too.

(Paradoxically, the fact that papers focus on implementation/results means that your talk is free to deemphasize them. People who are following the field may have already read your paper; people who aren’t following the field probably won’t understand the methodology or detailed results anyway. )

One exception is if there’s some personal or non-obvious story about implementation and results—if you wasted time on the wrong architecture or had some interesting realization that led to a breakthrough, these are great to include. I’ve often gone to talks just so I can hear any narrative details that aren’t “neat” enough to be in the paper.

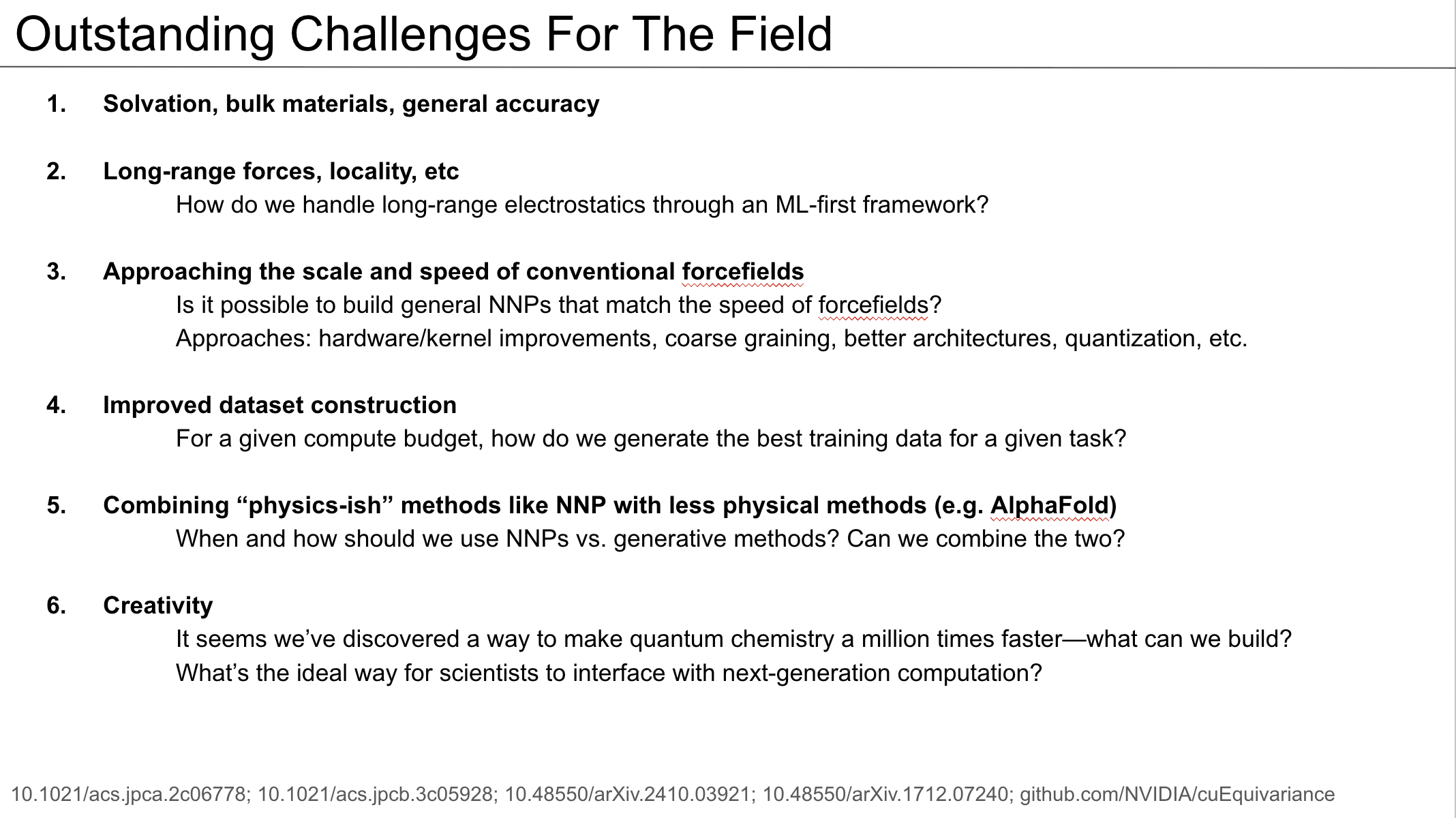

The ending discussion can vary a lot from talk to talk, but I think it’s worth stating clearly what you think the conclusions should be from your work. What should someone in the field take away? What should someone in an adjacent field take away? What do you predict the future of this area of research will be?

Here's the last slide from a talk I gave at MSU in February:

It’s always good to save at least 10 minutes within the allotted time for Q&A, and to leave time after the talk for additional questions.

Different people and fields have different customs here; there’s no hard-and-fast rule. I rarely make new figures for talks, because it takes forever—I’ll instead take images from existing papers and put the citations at the bottom.

A few disjointed thoughts: