In 2007, John Van Drie wrote a perspective on what the next two decades of progress in computer-assisted drug design (CADD) might entail. Ash Jogalekar recently looked back at this list, and rated the progress towards each of Van Drie’s goals on a scale from one to ten. There’s a lot in Jogalekar’s piece that’s interesting and worth discussing, but I was particularly intrigued by the sixth item on the list (emphasis added):

Outlook 6: today’s sophisticated CADD tools only in the hands of experts will be on the desktops of medicinal chemists tomorrow. The technology will disperse

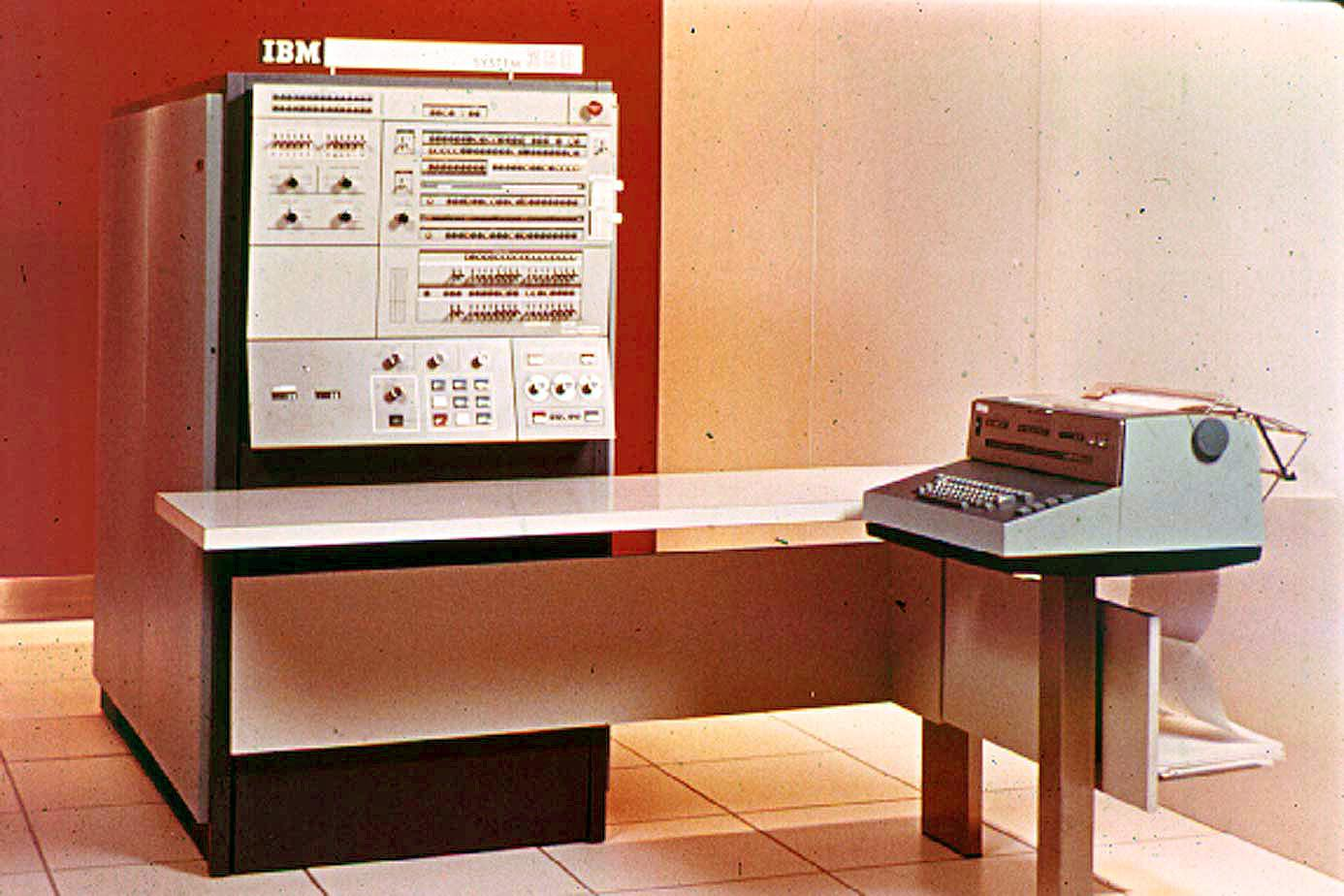

Twenty-five years ago, modelers worked with million-dollar room-sized computers with 3D display systems half the size of a refrigerator. Today, the computer which sits on my lap is far more powerful, both in computation speed and in 3D display capabilities. Twenty-five years ago, the software running on those computers was arcane, with incomprehensible user interfaces; much of the function of modelers in those days was to serve as a user-friendly interface to that software, and their assistance was often duly noted in manuscripts, if not as a co-author then as a footnote. Today, scientists of all backgrounds routinely festoon their publications with the output of molecular graphics software, running on their desktop/laptop machines with slick easy-to-use graphical user interfaces, e.g. Pymol.

This is a trend that will accelerate. Things that seem sophisticated and difficult-to-use, but are truly useful, will in 20 years be routinely available on desktop/laptop machines (and even laptops may be displaced by palmtops, multi-functional cellphones, etc.). Too many modelers are still in the business of being ‘docking slaves’ for their experimental collaborators (i.e. the experimentalist asks the modeler ‘please dock my new idea for a molecule’, and waits for the result to see if it confirms their design); this will ultimately disappear, as that type of routine task will be handled by more sophisticated user interfaces to current docking algorithms, e.g. the software from Molsoft is well on its way to fill such a role. Whereas the ‘information retrieval specialists’ that once populated corporate libraries have disappeared, replaced by desktop Google searches, this trend of modeling-to-the-desktop should not be a source of job insecurity for CADD scientists—this will free us up from the routine ‘docking slave’ tasks to focus our energies on higher-valued-added work. As a rule, things today that seem finicky and fiddly to use (e.g. de novo design software), or things that take large amount of computer resources (e.g. thermodynamic calculations, or a docking run on the full corporate database) are things that one can easily imagine will in the future sit on the desktops of chemists, used by them with minimal intervention by CADD scientists

Jogalekar gives the field a 6/10 on this goal, which I find optimistic. In his words:

From tools like Schrödinger’s Live Design to ChemAxon’s Design Hub, medicinal chemists now use more computational tools than they ever did. Of course, these tools are used in fundamental part because the science has gotten better, leading to better cultural adoption, but the rapidly dwindling cost of both software and hardware enabled the cloud has played a huge rule in making virtual screening and other CADD tools accessible to medicinal chemists.

It’s true that there are more computational tools available to non-computational scientists than there once were—but based on the conversations we’ve had with industry scientists (which also informed this piece), the role of computational chemists as “docking slaves” (Van Drie’s phrase, not mine) to their experimental colleagues still rings true. The number of experimental scientists able to also run non-trivial computational studies remains vanishingly low, despite the improvements in computing hardware and software that Van Drie and Jogalekar discussed.

Why hasn’t our field made more progress here? In my view, there are three principal reasons: immature scientific tools demand expert supervision, poorly designed technology deters casual usage, and cultural inertia slows adoption even further.

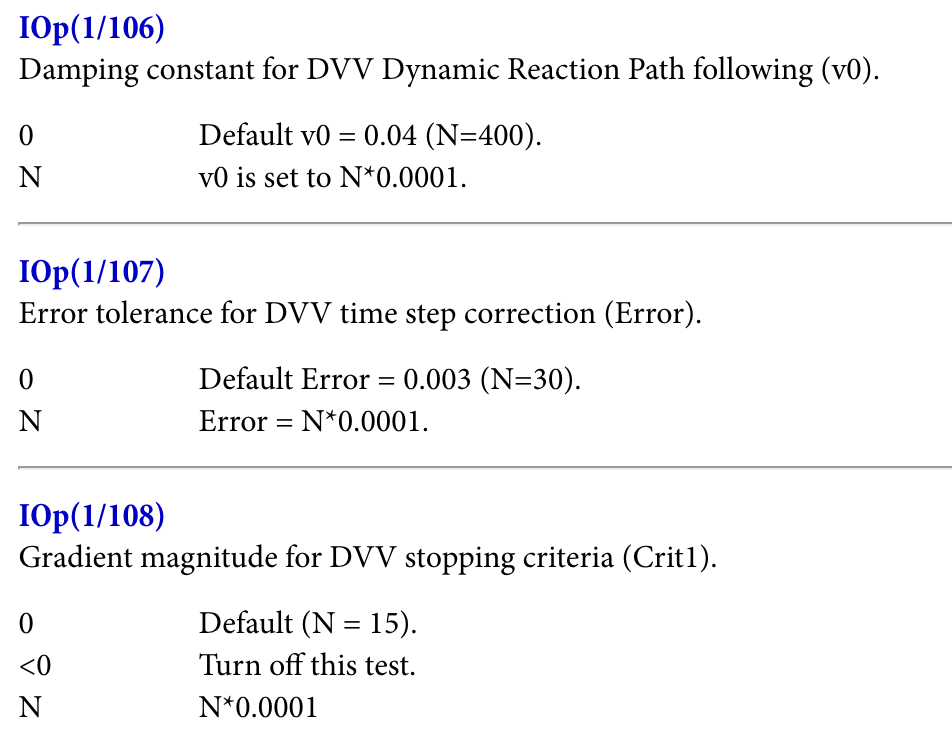

Most scientific tools optimize for performance and tunability, not robustness or ease of use. Quantum chemistry software forces users to independently select a density functional, a basis set, any empirical corrections, and (for the brave) allows them to tune dozens of additional parameters with obscure and poorly documented meanings. (“Oh, the default settings for transition states aren’t very good… you need to configure the initial Hessian guess, the integral tolerance, the optimizer step size, and a few other things… I’ll email you a couple scripts.”)

And these issues aren’t unique to quantum chemistry; virtually every area of scientific simulation or modeling has its own highly specialized set of tools, customs, and tricks, so switching fields even as a PhD-level computational chemist is challenging and treacherous. Some of this complexity is inherent to the subject matter—there are lots of unsolved computational problems out there for which no simple solution is yet known. For instance, handing changes in ionization state or tautomerization during free-energy-perturbation (FEP) simulations is (to my knowledge) just intrinsically difficult right now, and no robust solution exists that can be plainly put into code.

But better hardware and better methods can alleviate these issues. Searching through different conformers of a complex molecule used to be a challenging task that demanded chemical expertise and considerable software skill—now, metadynamics programs like CREST make it possible to run conformer searches simply from a set of starting coordinates. These new “mindless” methods are less efficient than the old methods that relied on chemical intuition, but in many cases the simulations are fast enough that we no longer care.

Similarly, the increasing speed of quantum chemistry makes it simpler to run high-accuracy simulations without extensive sanity checks. In my PhD research, I carefully benchmarked different tiny basis sets against high-level coupled cluster calculations to find a method that was fast enough to let me study the reaction dynamics of a catalytic transition state—now, methods like r2SCAN-3c give better accuracy in virtually every case and avoid the dangerous basis-set pathologies I used to worry about, making it possible to use them as a sane default for virtually every project.

Other fields have undergone similar transformations. Writing assembly code, when done right, produces substantially faster and more efficient programs than writing a compiled language like C, and writing C produces faster code than writing a high-level language like Python. But computers are fast enough now that writing assembly code is now uncommon. Python is much more forgiving, and makes it possible for all sorts of non-experts (like me) to write useful code that addresses their problems. Back in the days of the PDP-10, every FLOP was precious—but with today’s computers, it’s worth accepting some degree of inefficiency to make our tools quicker to learn, easier to use, and far more robust.

Computational chemistry needs to make the same transition. There will always be cutting-edge computational problems that demand specific expertise, and these problems will invariably remain the rightful domain of experts. But vast improvements in the speed and accuracy of computational chemistry promise to move more and more problems into a post-scarcity regime where maximum efficiency is no longer required and the field’s impact will no longer predominately be determined by performance.

Once a method becomes robust enough to be routinely used without requiring expert supervision, it’s safe to turn over to the non-experts. I’d argue that this is true of a decent proportion of computational workflows today, and advances in simulation and machine learning promise to make this true for a much greater proportion in the next decade.

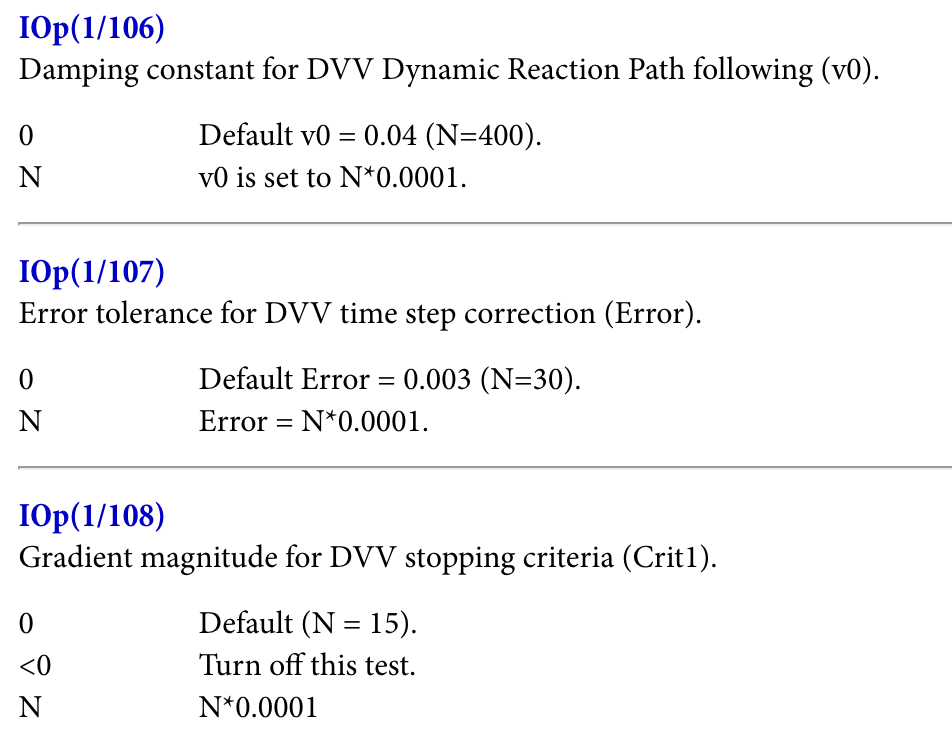

Sadly, scientific considerations aren’t all that prevents molecular modeling from being more widely employed. The second underlying reason limiting the reach of computational tools is that most of the tools are, frankly, just not very good software. Scientific software frequently requires users to find and manage their own compute, write scripts to parse their output files and extract the data, and do plenty of needless work in post-processing—in many respects, being a computational chemist means stepping back in time to 1970s-era software.

These difficulties are considerable even for full-time computational chemists; for experimental scientists without coding experience, they’re insurmountable. No medicinal chemist should need to understand rsync, sed, or malloc to do their job! Some of the error messages from computational chemistry software are so obtuse that there are entire web pages devoted to decrypting them:

RFO could not converge Lambda in 999 iterations. Linear search skipped for unknown reason. Error termination via Lnk1e in /disc30/g98/l103.exe. Job cpu time: 0 days 7 hours 9 minutes 17.0 seconds. File lengths (MBytes): RWF= 21 Int= 0 D2E= 0 Chk= 6 Scr= 1

Why is so much scientific software so bad? Academic software development prioritizes complexity and proof-of-concepts because these are the features that lead to publications. More prosaic considerations like robustness, maintainability, and ease of use are secondary considerations at best, and it’s hard for academic research groups to attract or maintain the sort of engineering talent required for most impactful work in scientific software. In a piece for New Science, Elliot Hirshberg documents the consequences of this situation (emphasis added):

…most life sciences software development happens in academic labs. These labs are led by principal investigators who spend a considerable portion of their effort applying for competitive grants, and the rest of their time teaching and supervising their trainees who carry out the actual research and engineering. Because software development is structured and funded in the same way as basic science, citable peer-reviewed publications are the research outputs that are primarily recognized and rewarded. Operating within this framework, methods developers primarily work on building new standalone tools and writing papers about them, rather than maintaining tools or contributing to existing projects….

This organizational structure for developing methods and software has resulted in a tsunami of unusable tools…. Scientists need to learn how to download and install a large number of executable programs, battle with Python environments, and even compile C programs on their local machine if they want to do anything with their data at all. This makes scientists new to programming throw up their hands in confusion, and seasoned programmers tear their hair out with frustration. There is a reason why there is a long-running joke that half of the challenge of bioinformatics is installing software tools correctly, and the rest is just converting between different file formats.

Frustratingly, relatively few academic scientists seem to view this as a problem. In a thread discussing the lack of graphical user interfaces (GUIs) for scientific software on the Matter Modeling Stack Exchange, a user writes about how GUIs are not just a distraction but actively harmful for scientific software (emphasis added):

[GUI development takes time] that could be spent on other tasks, like developing more functionality in the core program, developing different programs for different tasks, or even doing other things like lab research that has clearer advantages for one’s career… But then, after the GUI has been designed and created, it’s a new source of maintenance burden. That means a program with a GUI will have to have time dedicated to fixing GUI issues for users, especially if an OS (or other system library) update breaks it. That’s time that could be spent on other things more productive to one’s career or research aspirations.

This is a textbook case of misaligned incentives. Researchers who create scientific software aren’t rewarded for making it easy for others to build on or use, only for making it increasingly powerful and complex—as a result, there are hundreds of complex and impossible-to-use scientific software packages floating around on Github. Almost all the scientific software projects which defy this trend are commercial or supported by commercial entities: at least from the users’ point of view, the incentives of a for-profit company seem superior to academic incentives here.

Better tools are the solution to the ever-increasing scientific burden of knowledge. Every day, experimental scientists use tools without fully understanding their internal workings—how many chemists today could build a mass spectrometer from scratch, or an HPLC? We accept that experimental tools can be productively used by non-experts who don’t understand their every detail—but when it comes to computational chemistry, we expect every practitioner to build their own toolkit practically from scratch.

This has to change. If we want scientific software to be more widely used, our field needs to find a way to make software that’s as elegant and user-friendly as the software that comes out of Silicon Valley. This can happen through any number of different avenues—improved academic incentives, increased commercial attention, and so on—but without this change, large-scale democratization of simulation will never be possible.

But even with robust methods and well-designed software products, cultural differences between computational and experimental scientists persist. Generations of PhD students have been taught that they’re either “computational” or “experimental,” with the attendant stereotypes and communication barriers that accompany all such dichotomies. In industry, scientists are hired and promoted within a given skillset; while scientists occasionally hop from experiment to computation, it’s rare to meet truly interdisciplinary scientists capable of contributing original research insights in both areas.

Many scientists, both computational and experimental, are happy with this state-of-the-art. Experimental scientists can avoid having to learn a set of confusing skills and delegate them to a colleague, while maintaining a comfortable skepticism of any computational predictions. Computational scientists, in contrast, get to serve as “wizards” who summon insights from the Platonic realm of the computer.

Some computational scientists even come to take pride in their ability to navigate a confusing web of scripts, tools, and interfaces—it becomes their craft, and a culture to pass along to the next generation. On Stack Exchange, one professor writes in response to a beginner asking about graphical user interfaces:

Trust me: it is better to learn the command line… I began using UNIX when I was 9 years old. It’s time for you to learn it too.

As Abhishaike Mahajan put in his poster about Rowan—“enough”! It doesn’t have to be this way.

Why care about democratizing simulation? We think that putting simulation into the hands of every scientist will enable innovation across the chemical sciences. As of 2025, it seems clear that computation, simulation, and ML will play a big role in the future of drug discovery. But as long as “computation” remains a siloed skillset distinct from the broader activity of drug discovery, the impact that these breakthroughs can have will remain limited by cultural and organizational factors.

If the importance of computer-assisted drug discovery continues to increase but the tools remain unusable by the masses, will computational chemists and biologists simply grow in importance more and more? Taken to the extreme, one can envision what Alice Maz terms “a priesthood of programmers,” a powerful caste dedicated to interceding between man and computer. Perhaps computational tools will remain inaccessible forever, and those who excel at drug discovery will be those who can best deploy a litany of arcane scripts. Perhaps the future of chemistry will be run by CS majors, and today’s drug hunters will merely be employed to synthesize compounds and run biological assays in service of the new elite.

But one can envision a future in which computational chemistry becomes a tool to aid drug designers, not supplant them. In 2012, Mark Murcko and Pat Walters (distinguished industry scientists both) wrote “Alpha Shock,” a speculative short story about drug discovery in the year 2037. I want to highlight a scene in which Sanjay (the protagonist) uses structure-based drug design to discover a new candidate and avoid paying his rival Dmitri royalties:

With the structures and custom function in hand, Sanjay was ready to initiate the docking study. But despite recent advances in the TIP32P** water model, Sanjay still didn’t completely trust the predicted protein-ligand binding energetics. Next, he transferred the experimental data into the Google Predictive Analytics engine and quickly designed a new empirical function to fit the experimental data. Now he launched the dynamic docking simulator, dropping the empirical function into the hopper... A progress bar appeared in front of him showing “10^30 molecules remaining, 2,704 h 15 min to completion.” Sanjay quickly stopped the process and constrained the search to only those molecules that fell within the applicability domain of his empirical function. This reduced the search to 10^12 molecules and allowed the analysis to complete in a few minutes.

After a bit of visual inspection to confirm the results of his docking study, Sanjay moved on to the next step. He knew that slow binding kinetics could provide a means of lowering the dose for his compound. To check this, he ran a few seconds of real-time MD on each of the top 50,000 hits from the docking study. A quick scan of the results turned up 620 structures that appeared to have the required residence time. Sanjay submitted all these structures to PPKPDS, the Primate Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Simulator, a project developed through a collaboration of industry, academia, and the World Drug Approval Agency. Of the compounds submitted, 52 appeared to have the necessary PK profile, including the ability to be actively transported into the brain. All but a few were predicted to be readily synthesizable.

In “Alpha Shock,” a drug designer like Sanjay can leverage interactive, intuitive software to quickly test his hypotheses and move towards important conclusions. Sanjay’s tools serve to augment his own intuition and vastly increase his productivity, yet don’t require him to use bespoke scripts or memorize arcane incantations. To anyone with any experience with computer-assisted drug design, this will read like science fiction—but that is exactly the point. The world of “Alpha Shock” gives us a vision of where we need to go as a field, and highlights where we’re deficient today.

Better instrumentation and analytical tooling has revolutionized chemistry over the past sixty years, and better design & simulation tools can do the same over the next sixty years. But as we’ve seen with NMR and mass spectrometry, enabling technologies must become commonplace tools usable by lots of people, not arcane techniques reserved for a rarefied caste of experts. Only when computational chemistry undergoes the same transition can we fulfill the vision that Van Drie outlined years ago—one in which every bench scientist can employ the predictive tools once reserved for specialists, and in which computers can amplify the ingenuity of expert drug designers instead of attempting to supplant it.

Thanks to Ari Wagen for feedback on drafts of this piece.