Update: As of October 2024, you can now run DiffLinker calculations through Rowan, my computational chemistry startup. Read more about this in our newsletter!

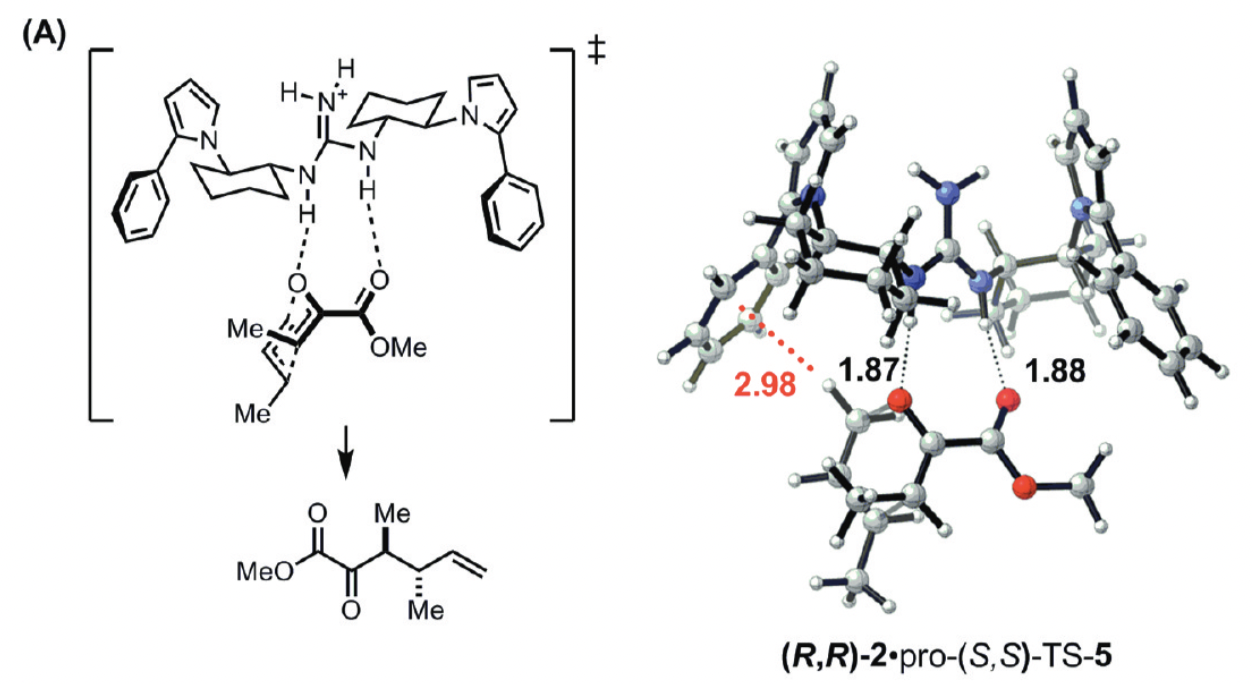

Much molecular design today can be boiled down to “put the right functional groups in exactly the right places.” In catalysis, proper positioning of functional groups to complement developing charge or engage in other stabilizing non-covalent interactions with the transition state can lead to vast rate accelerations. A classic demonstration of this is Uyeda and Jacobsen’s enantioselective Claisen rearrangement, where a simple catalyst presents a guanidinium ion to stabilize an anionic region and an electron-rich arene to stabilize a cationic region. Together, these interactions lead to high enantioselectivity and a 250-fold rate increase over the background reaction.

While putting the right functional groups in the right positions might sound easy, the underlying interactions are often exquisitely sensitive to distance, which makes finding the right molecular scaffold very challenging. Jeremy Knowles put this nicely in his 1991 perspective on enzyme catalysis:

Although it is too early to generalize, it is evident that in this case [triose phosphate isomerase] at least, the positioning of functionality at the active site of the enzyme needs to be quite precise if full catalytic potency is to be realized… The good news for catalyst engineers is that proper placement of appropriate groups in the right environment seems to be enough. The not-so-good news is that this placement must be very precise.

Proper positioning of various groups isn’t just a problem in catalysis—it’s also very important in drug design. Lots of topics in medicinal chemistry essentially boil down to a variant of the positioning problem:

Finding the right linker motif, which orients the individual fragment units in the favourable geometry in relation to each other without introducing too much flexibility whilst maintaining the binding poses of both fragments, can be very challenging. If successful, the combination of two fragments with rather low affinity could result in significantly higher affinity and has the potential to result in “superadditive” contributions of both binding motifs. The challenge in fragment linking is the exploration of the binding mode of both fragments and the identification of an optimal linker. Only in this case, the overall reduced so-called rigid body entropy translates into synergistically-improved affinity.

What’s hard about all these positioning problems is that finding a molecule that orients substituents in a given way is incredibly non-obvious: molecules are inherently discrete and atomic, making it hard to change a distance or angle by a precise percent. You can have two carbon atoms between your substituents, or you can have three carbon atoms, but you can’t have 2.5 carbon atoms. This makes prospective design very challenging: I can model my protein’s active site and figure out that I want a an ortho-pyridyl substituent and a tetrazole 8 Å apart at a 30º angle, but working backwards to an actual scaffold almost always requires a lot of trial and error.

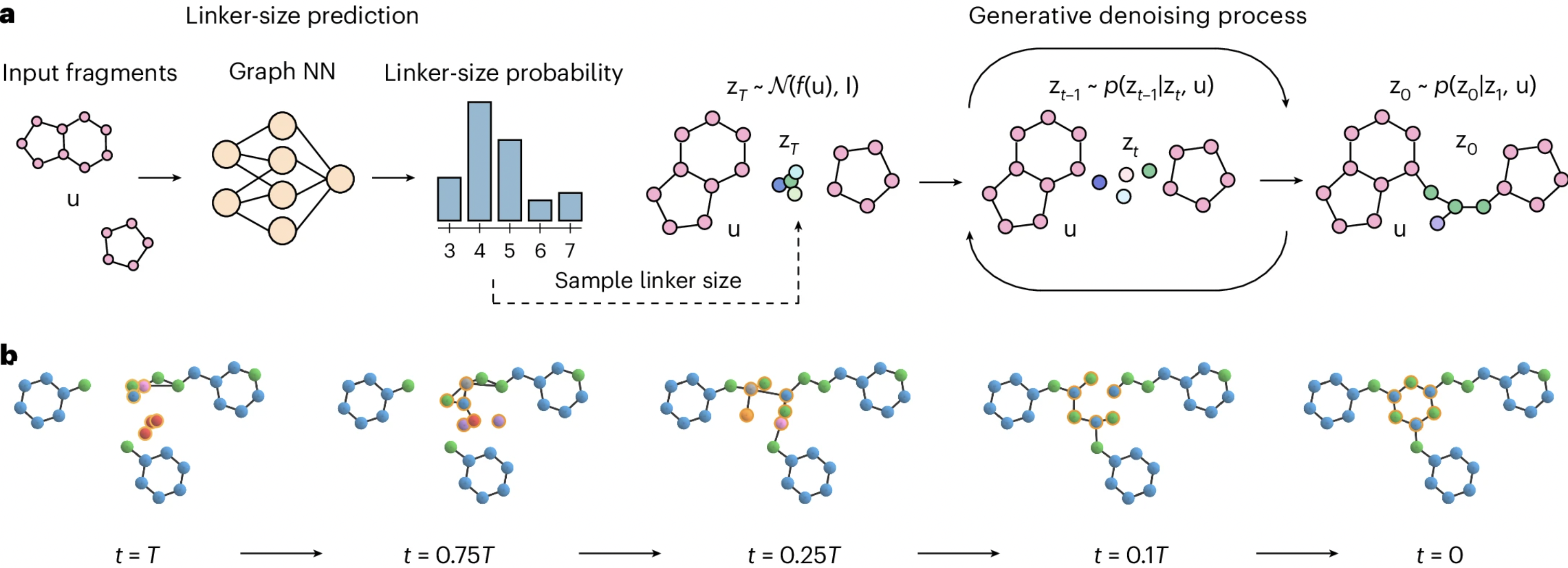

A recent paper from Ilia Igashov and co-workers sets out to solve exactly this “inverse design” problem: given two substituents, can we use ML to find a linker that connects them in the desired orientation? Their solution is DiffLinker, a diffusion-based method that takes separate atomic fragments and generates a linker that connects them.

There’s been other work in this area, but the DiffLinker authors argue that their model stands out in a few ways. DiffLinker generally produces more synthetically accessible and drug-like molecules than competitor methods, although the relative ranking of models does change significantly from benchmark to benchmark. Also, they’re not limited to joining pairs of molecule structures: DiffLinker can perform “one-shot generation of the linker between any arbitrary number of fragments,” which lets them vastly outperform other models when linking three or more fragments.

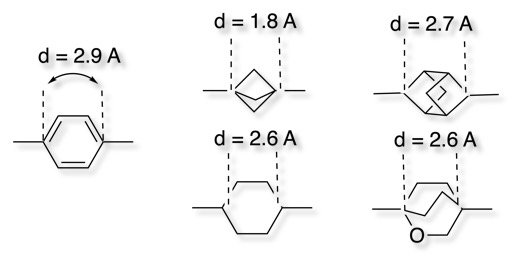

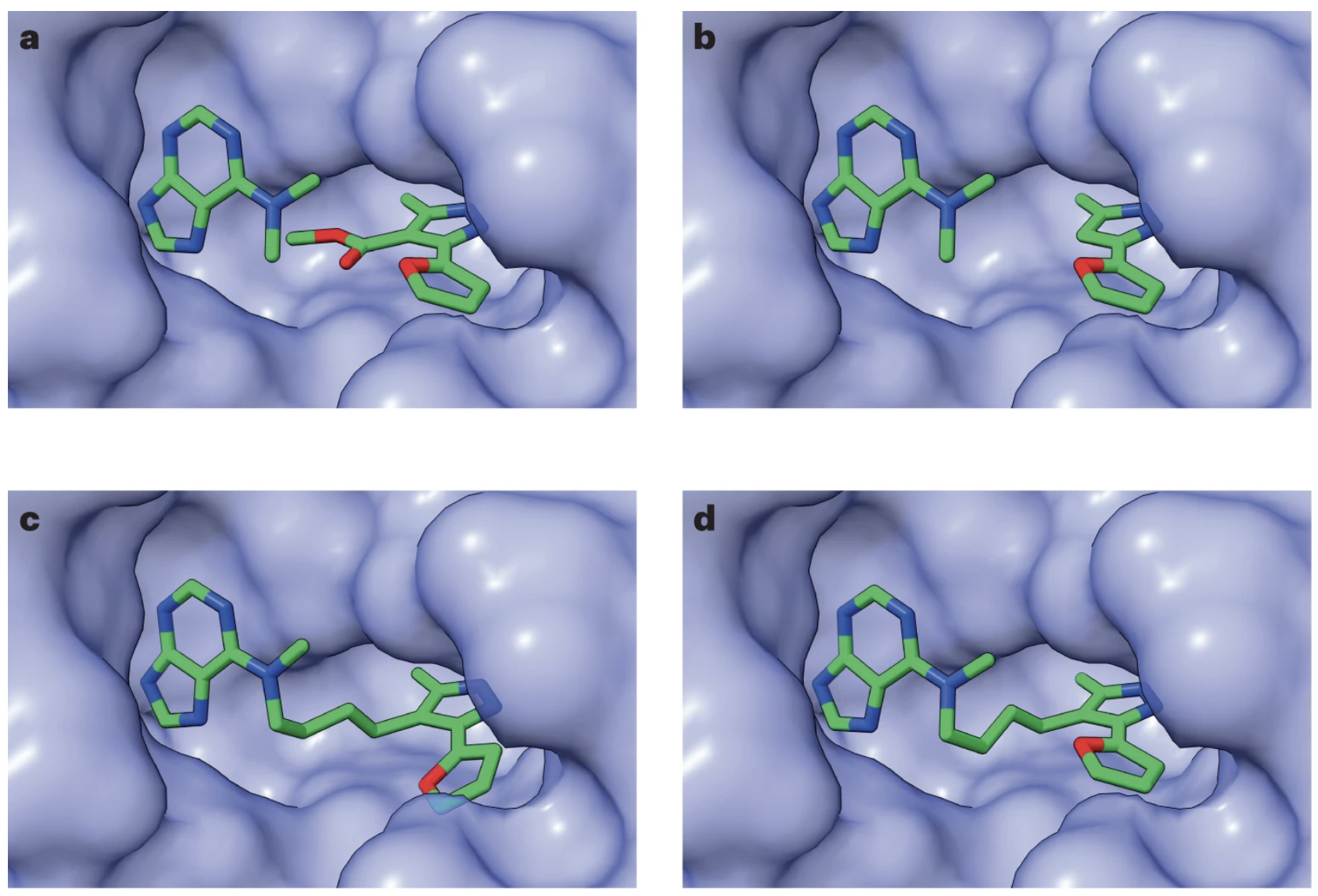

For cases where fragments must be joined in a protein pocket, the authors train a pocket-conditioned model, and show that this model results in many fewer clashes than an unconstrained model. They can use this model to recapitulate known drug structures, which they demonstrate with a known HSP90 inhibitor derived from molecular fragments. (It’s worth noting that the authors got the desired inhibitor structure only 3 times out of 1000 DiffLinker predictions.) They also show that their protein-conditioned model produces molecules that have good binding affinity as assessed by docking (GNINA/Vina), with the huge caveat that docking scores are notoriously inaccurate.

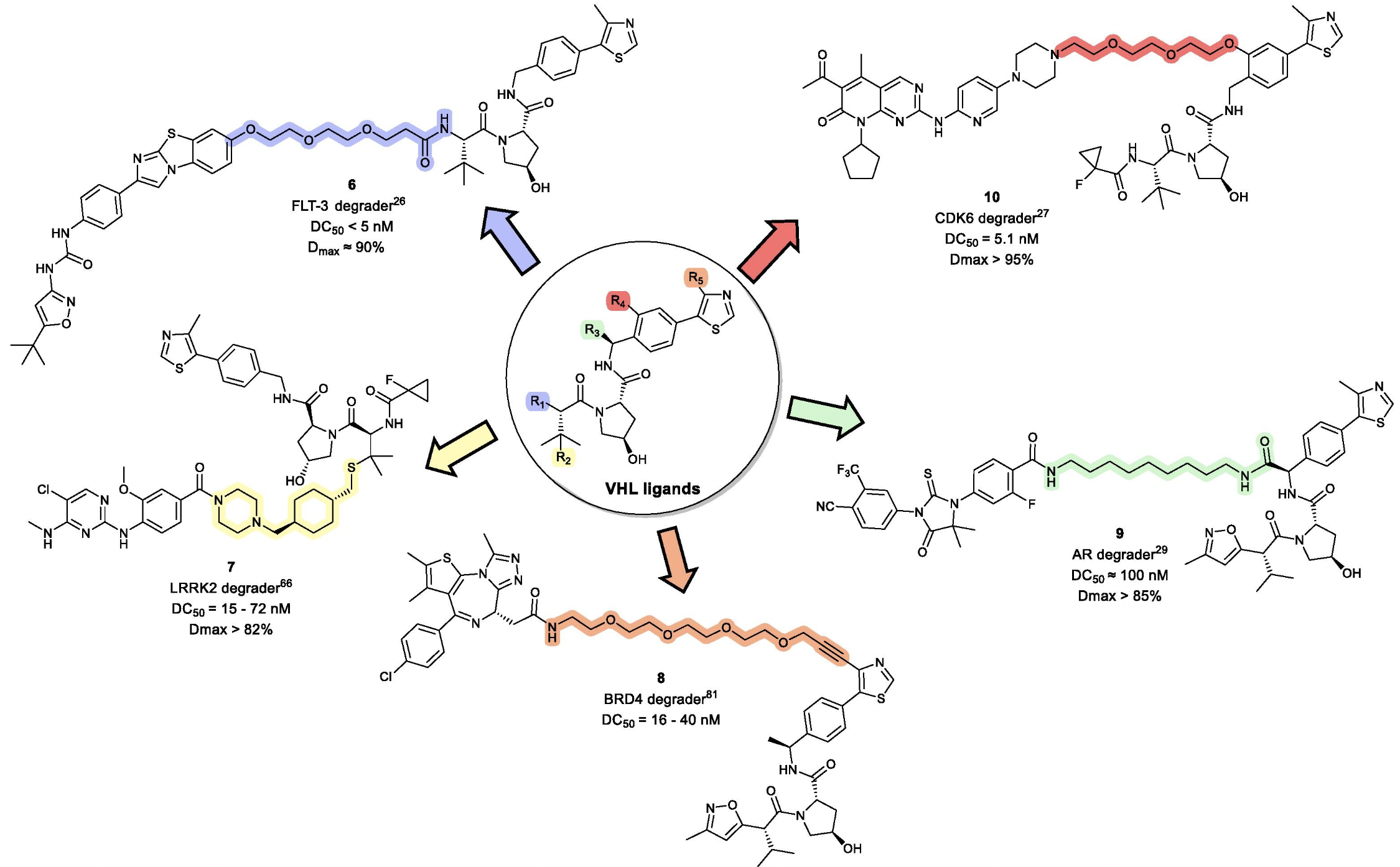

There’s still plenty of work that needs to be done here: for instance, the authors readily acknowledge that PROTACs are still too challenging:

While DiffLinker effectively suggests diverse and valid chemical structures in tasks like fragment linking and scaffold hopping, we have observed that generating relevant linkers for PROTAC-like molecules poses a greater challenge. The main difference between these problems lies on the linker length and the distance between the input fragments. While the average linker size in our training sets is around 8 atoms (5 for ZINC, 10 for GEOM, 10 for Pockets), a typical linker in a PROTAC varies between 12 and 20 atoms. It means that the distribution of linkers in PROTACs has different characteristics compared to the distributions of linkers provided in our training sets. Therefore, to improve the performance of DiffLinker in PROTAC design, one may consider retraining the model using more suitable PROTAC data.

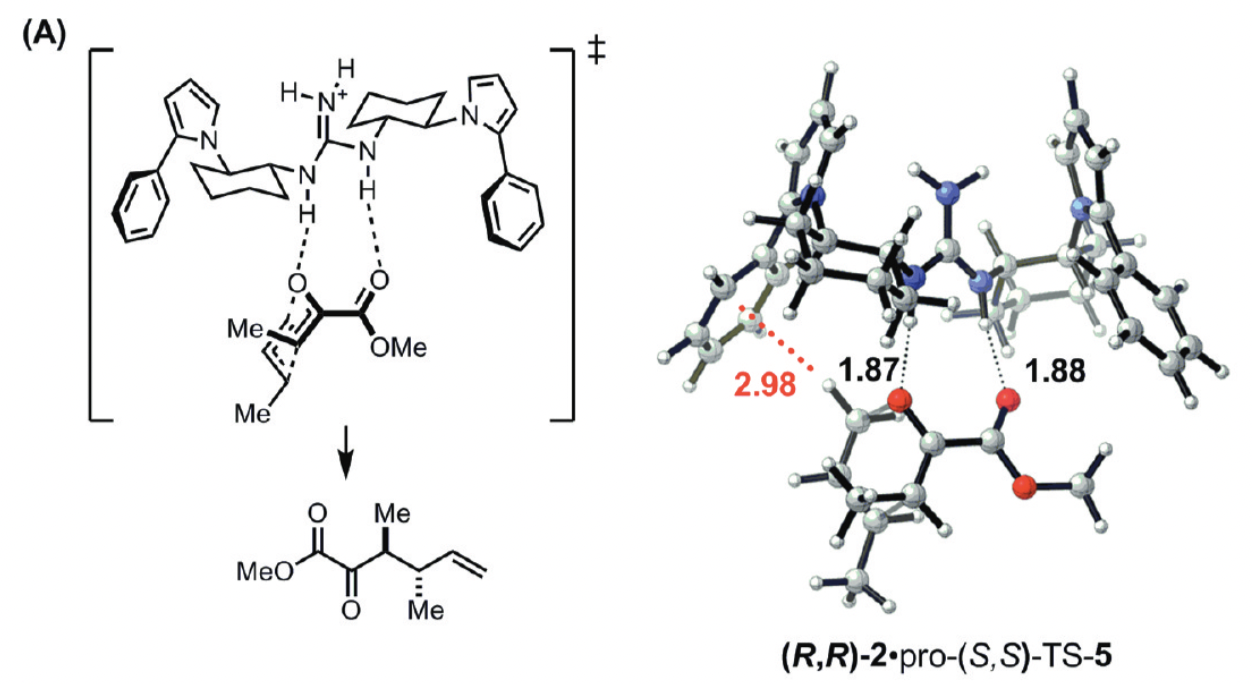

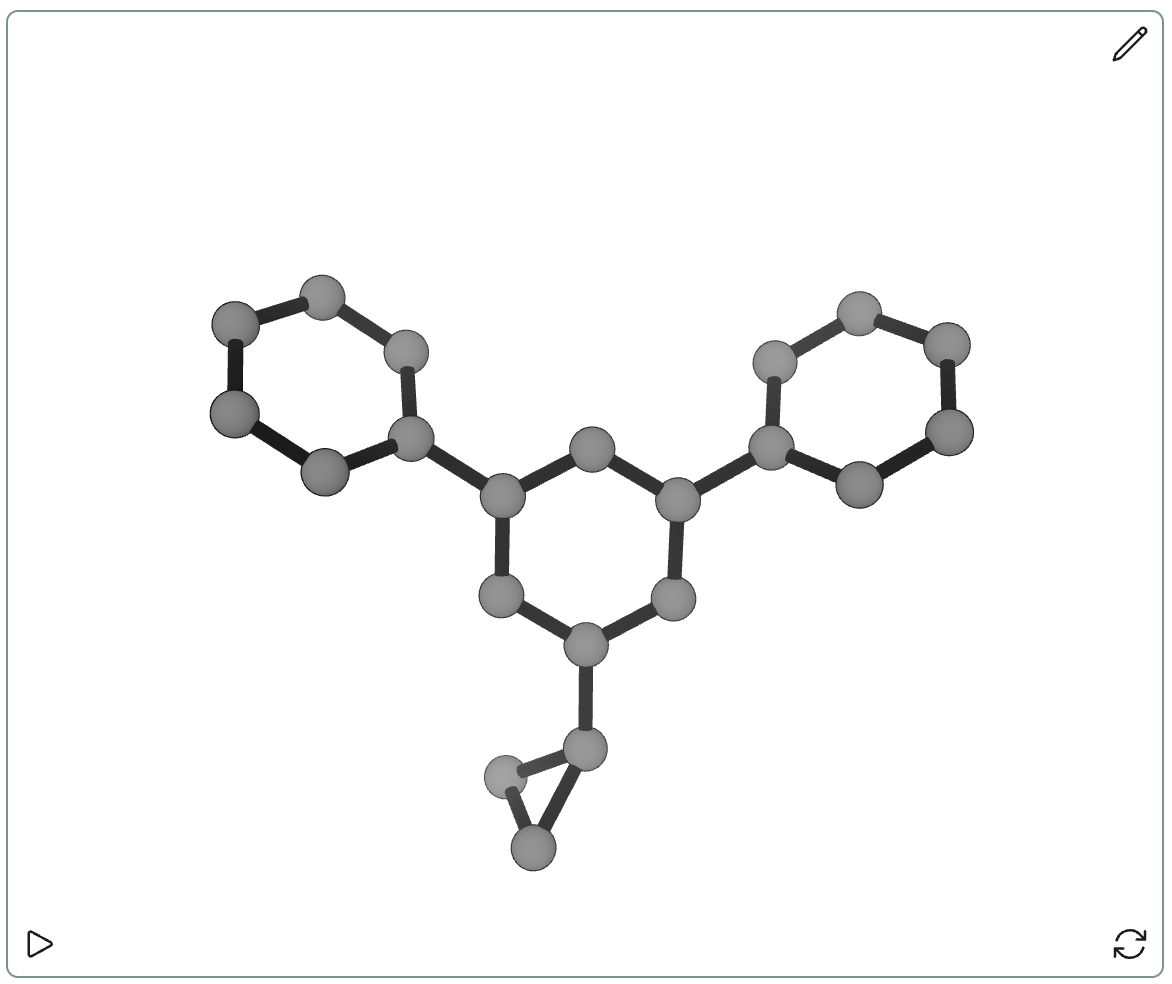

DiffLinker is open-source and comes with pre-trained models, so I played around with it a bit myself to see how well it worked. I sketched out a classic meta-terphenyl scaffold, deleted the central phenyl ring, and then asked DiffLinker to connect the now-separated phenyl rings. I was hoping that DiffLinker would come up with one of Enamine’s cool suggestions for meta-arene bioisosteres, but in all five cases I just got back some variant on a benzene ring… which isn’t surprising in hindsight.

Although I don’t think this version of DiffLinker is going to replace humans at any of the tasks I talked about above, this still seems like a pretty cool direction for generative chemical ML. I’m excited to see future versions of methods like DiffLinker that are able to generate predictions conditioned on other molecular properties to allow for guided exploration of molecular space. (For instance, it would have been nice to request fragments that were three-dimensional above, so as to avoid getting boring benzenes back.)

I also suspect that DiffLinker, like other generative chemical models, will increase the demand for accurate physics-based methods for refining and validating the output predictions. DiffLinker’s grasp of potential energy surfaces is presumably worse than DFT or other dedicated ML potentials, and a hybrid workflow where DiffLinker generates structures and a higher-quality method optimizes and scores them will probably be much more accurate than just DiffLinker alone. Generative AI is having a moment right now, but for better or worse I think “classic” molecular simulation is here to stay too.