Apologies for the long hiatus: we've had some health issues in the family, and startup life has been particularly overwhelming. With any luck, I'll be able to return to a more regular posting frequency soon.

What’s the right relationship between theory, computation, and experiment? Much has been written on this. In this piece, I want to put forward an answer that I think is underrated in the life sciences—what I call the “SolidWorks model” of simulation.

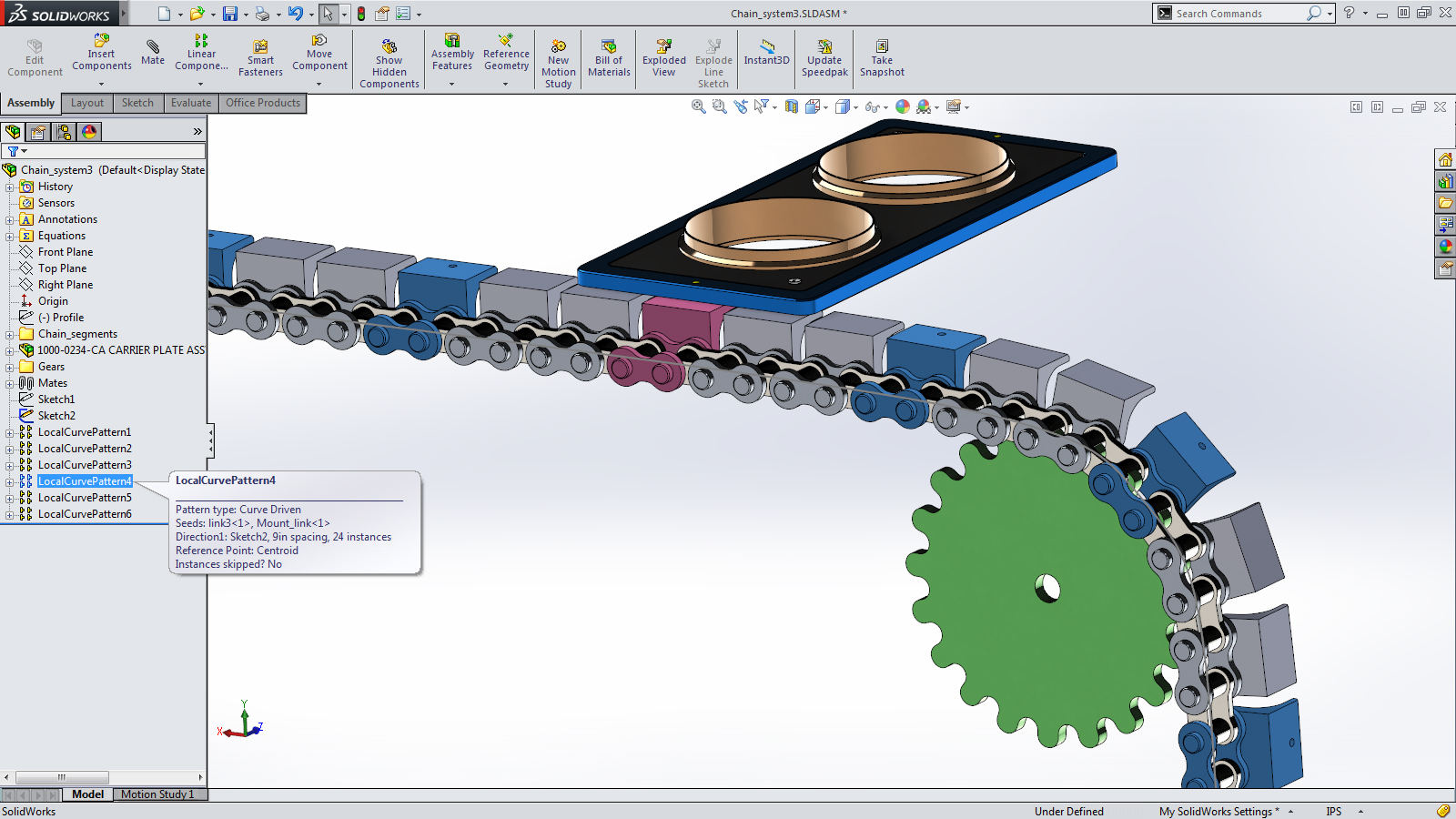

For the unfamiliar, SolidWorks is a program which allows engineers to design objects in the computer: the user can create a 3D model of their device, figure out the measurements that allow the parts to fit together in the desired way, and then go into the lab and actually build everything. (I’m not a SolidWorks power user, but I spent a semester messing around with it in high school and I’ve been thinking back on this recently.)

What are the distinctive features of SolidWorks?

Astute readers will notice differences from how simulations in the life sciences are typically conducted. It’s rare in chemistry or biology to have computations and experiments performed in the same research group, let alone by the same person—but this is crucial to SolidWorks-style simulation, where experimental scientists must quickly gain insight from their computations. If someone from a different team has to get around to answering their request or a job takes overnight to run, the experimental scientist will move on and modeling will be excluded from the design/build/test cycle.

SolidWorks-style computation is also prospective, not retrospective. In other words, the goal of the simulation is to generate subsequent experimental hits, not figures for publication, meaning that successful computational studies might never even be reported. This is different from the DFT section of the average organic chemistry paper, which is typically performed by a different team after all experimental results are complete. This isn’t bad, but ex post studies are different from actually using computations ex ante to design molecules.

I don’t mean to suggest that the SolidWorks paradigm is objectively correct: there are many ways in which theory, computation, and experiment can usefully interact, and I think it’s great that there are scientists using careful ex post computations to interpret perplexing experimental results or running massive virtual screens to design new molecules entirely in silico. I myself have worked on plenty of projects like this and hope to conduct more in the future.

But I do think that SolidWorks-style computation is pretty underrated today. There are few computational tools that non-experts can really use, and the average experimental scientists might not interact with computation even once in an average week (except perhaps when meeting with someone from a different lab or team). Even when experimentalists have the technical skills to run calculations, the friction involved in connecting to a computing cluster, generating input files, monitoring jobs, etc often makes it impractical to really run calculations and experiments in tandem.

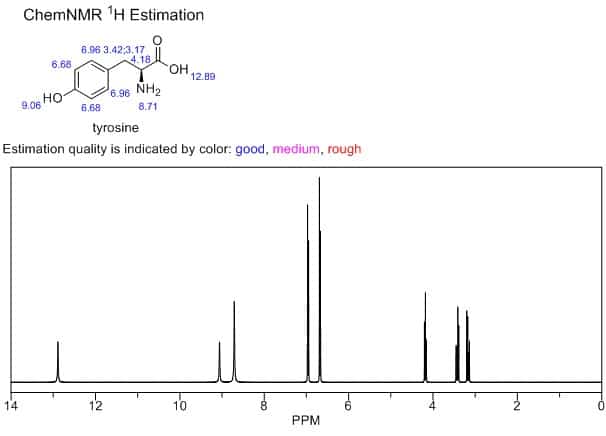

In fact, I’d argue that the most useful predictive computational tool for organic chemists has probably been the ChemDraw “Predict NMR” button. The predictions are laughably crude by today’s standards, but ChemDraw NMR has a few key advantages: (1) you don’t have to program anything or look at a terminal window to use it, (2) there aren’t any options for end users to mess around with, so you can’t do anything wrong, and (3) it runs instantly from a software package everyone already has, so it fits right into your workflow. These factors are collectively more important than accuracy—ChemDraw NMR is accurate enough to be useful, and far more convenient than fancier approaches.

This seems like a scenario where publication pressure leads to misaligned incentives. Scientific publications emphasize novelty, accuracy, and performance, not pragmatic considerations like “how easy is it to run this software in the middle of the workday” or “how confusing are the parameters to understand.” And for pioneering computational workflows that ought not to be run without a deep understanding of the science, that’s probably appropriate. But pragmatic considerations matter for casual users.

If it’s not obvious by now, one of our big visions for Rowan is “SolidWorks for organic chemistry”—to the extent that there are people who are designing and creating new molecules, we think that it’s important that they are able to think intelligently about the molecules that they’re designing. This means making software that can deliver actionable insights while being fast and simple enough for experimentalists to use. While this is a massive project, it’s not impossibly large, and we’re optimistic that Rowan can quickly become helpful to experimental chemists. If you think this vision is exciting and have ideas for how we can bring it to life, let us know!