In Wednesday’s post, I wrote that “traditional physical organic chemistry is barely practiced today,” which attracted some controversy on X. Here are some responses:

(There are plenty more responses; if I didn’t list yours, sorry!)

For the most part, I agree with these responses. Physical organic thinking has permeated organic chemistry and adjacent fields: George Whitesides has probably the best piece on this topic, in which he argues that the essence of physical organic chemistry is “a general, and remarkably versatile, method for tackling complex problems,” not anything about chemistry per se, and consequently that the physical organic mindset can be applied to problems in all manner of fields. Viewed from this angle, we might say that physical organic chemistry hasn’t disappeared at all—instead, it’s become so commonplace that we forget to acknowledge it as distinctive at all.

Looking through the organic chemistry curriculum, too, suggests that physical organic chemistry is here to stay. Lots of the ideas that we teach to undergraduates, like molecular orbital theory and structure–activity relationships, were once distinctively the domain of physical organic chemists. Textbooks from before the apotheosis of physical organic chemistry (I have an old copy of Fieser & Fieser, for instance) are structured in a completely different way, not by mechanism but by functional group, while today many undergraduate organic classes discuss SN1/SN2 mechanisms in their first semester.

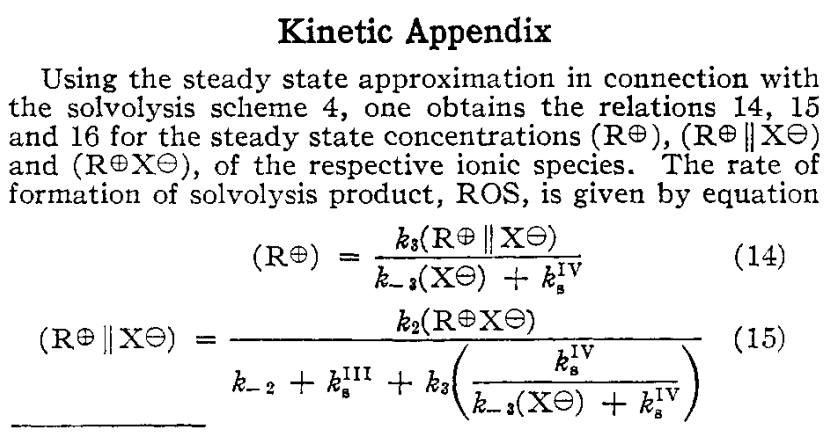

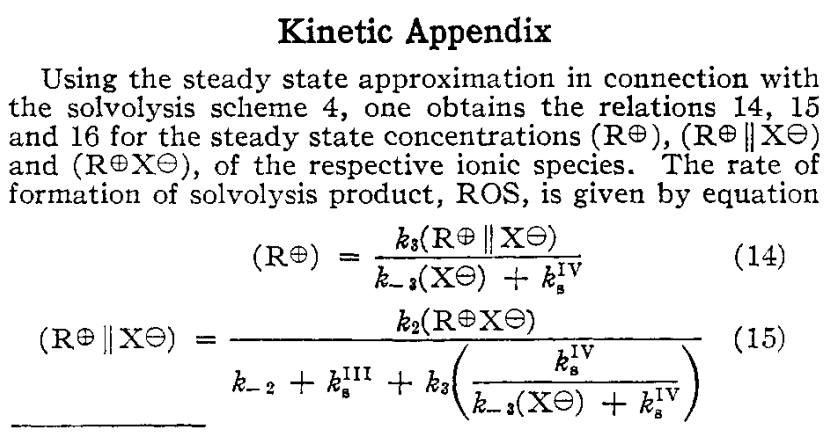

So, was I entirely wrong to claim that traditional physical organic chemistry is a dying art? I don’t think so. Despite all the successes of physical organic chemistry, it seems to me that something has been lost between the time of the norbornyl cation controversy and today. The sorts of elegant kinetic experimentation and argumentation that Winstein and others employed in their papers are now rare: take, for instance, this famous paper distinguishing between contact ion pairs and solvent-separated ion pairs. How many scientists today still do experiments like this? There are certainly names that come to mind, but from where I sit it seems to be an increasingly niche skillset.

I don’t want to fall into the trap of idolizing the past for no reason; there are plenty of techniques which have been forgotten by chemistry because there are better ways of doing the same thing today. Chemists used to estimate molecular weight by dissolving a known mass of sample and measuring the boiling point elevation induced. Now we have mass spectrometry, so nobody uses the boiling point method any more, and I don’t see this as a great tragedy.

But kinetics, and more generally the sort of careful physical organic chemistry practiced by participants in the norbornyl cation debate, doesn’t seem to have such a simple replacement. Computation is the most obvious candidate, but we’re still a long way away from being able to predict mechanisms accurately in silico; in mechanistic chemistry, experiments still reign supreme. Kinetic isotope effects are much easier to measure than they were back in Winstein’s day, but they’re hardly routine experiments (and easy to get wrong). The rigor and precision with which old-school physical organic chemistry approached mechanistic problems can still be found today, but it seems harder and harder to find.

It might have been inevitable that physical organic chemistry was always going to evolve away from incredibly detailed studies of simple reactions on simple molecules—just as biology has largely shifted from ecology and taxonomy to cell biology and biochemistry, organic chemistry too must change in order to keep working on the most interesting problems. And perhaps there's some truth to the argument that the old-school style of painstaking mechanistic study just isn't worth the effort and deserves to be de-emphasized. But it does seem to me that parts of the tradition of physical organic knowledge (to borrow Samo Burja’s phrasing) is being slowly lost to time, despite the fact that lots of really good physical organic chemistry is still being done today on all sorts of problems (enzymatic chemistry, organometallic chemistry, catalysis, heterogenous catalysis, chemical biology, &c), and that makes me sad.