In this post, I’m trying something new and embedding calculations on Rowan alongside the text. You can view the structures and energies right in the page, or you can follow a link and view the full data in a new tab. While PDFs and printed journals are limited to displaying 2D renditions of 3D structures, there’s no reason why websites should follow suit—and now that all my calculations are already on the web, it’s simple to share the primary data.

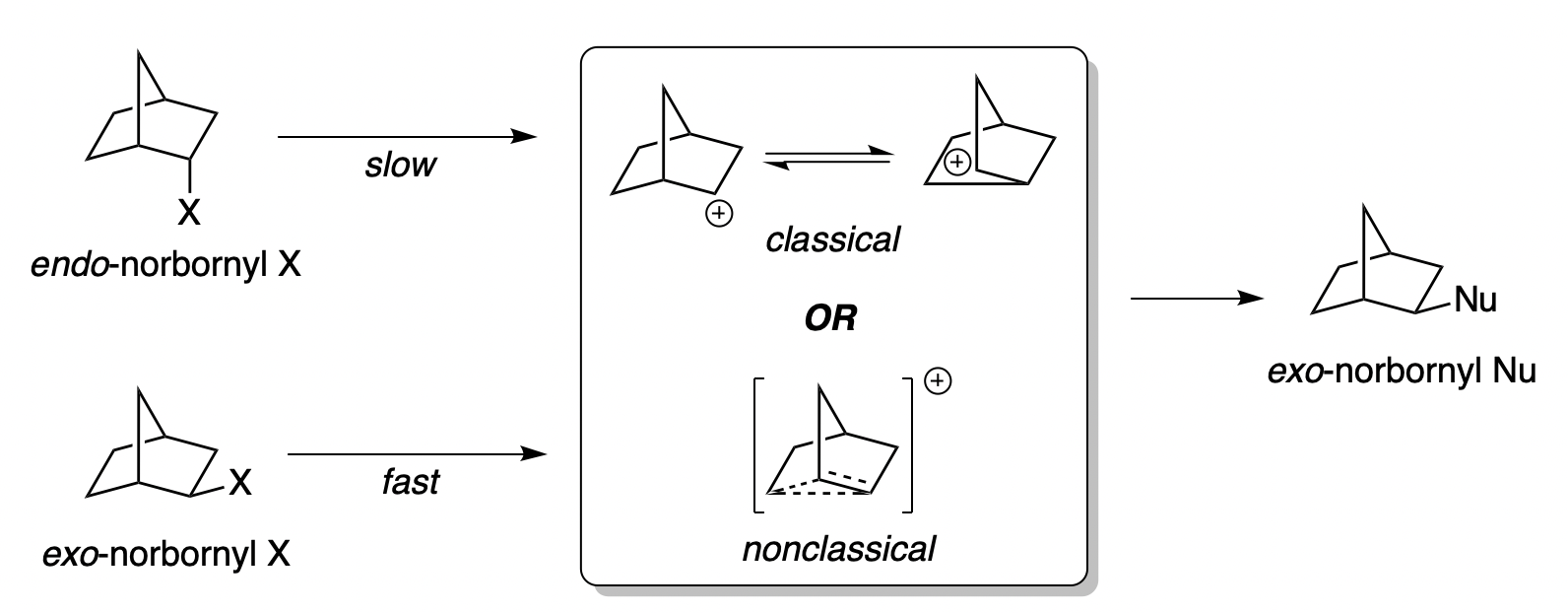

The 2-norbornyl cation has a special place in the history of physical organic chemistry. In 1949, following up on previous work by Christopher Wilson, the great physical organic chemist Saul Winstein observed that acetolysis of exo-norbornyl sulfonates occurred about 350 times faster than solvolysis of the corresponding endo compounds.

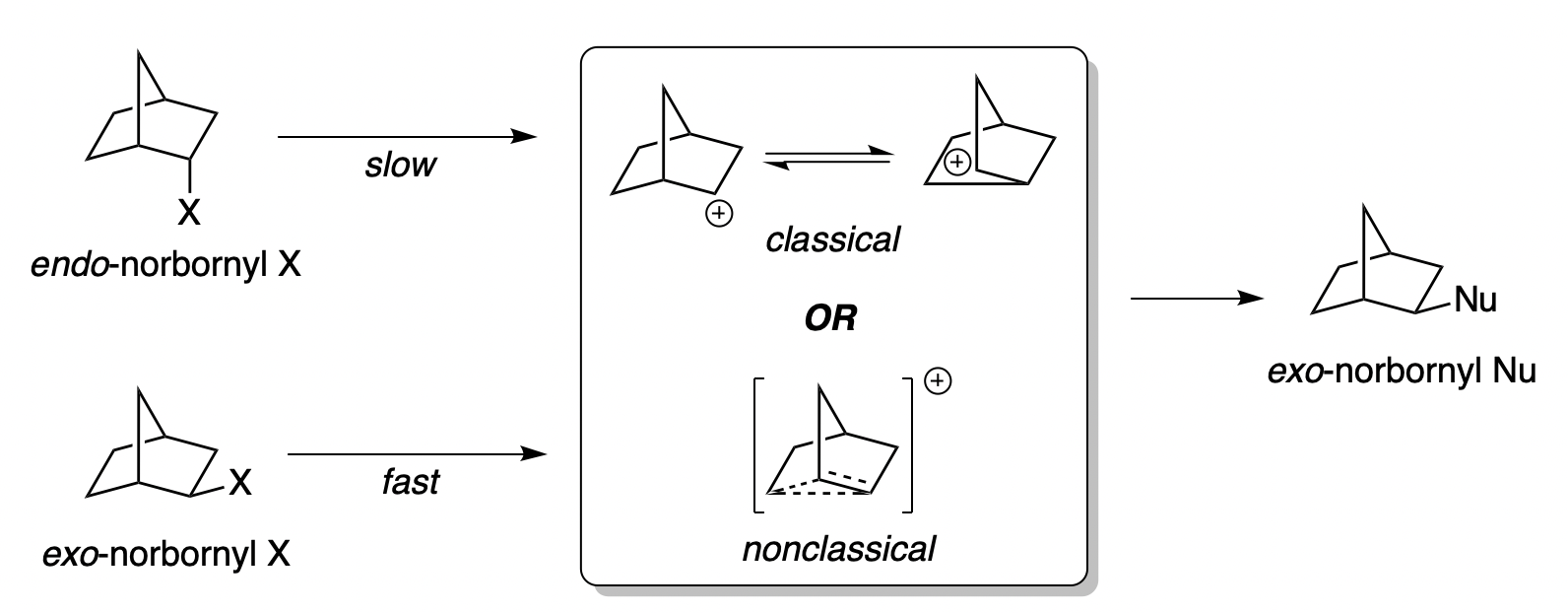

Several stereochemical observations indicated that something puzzling was going on: both the exo and endo sulfonates gave exo acetate product, but enantioenriched exo-norbornyl sulfonate formed racemic exo-norbornyl acetate. Winstein argued that this data was best explained through the participation of an achiral nonclassical carbocation (“II”) featuring σ-delocalization and a three-center two-electron bond, as shown in the conclusion of the 1949 paper:

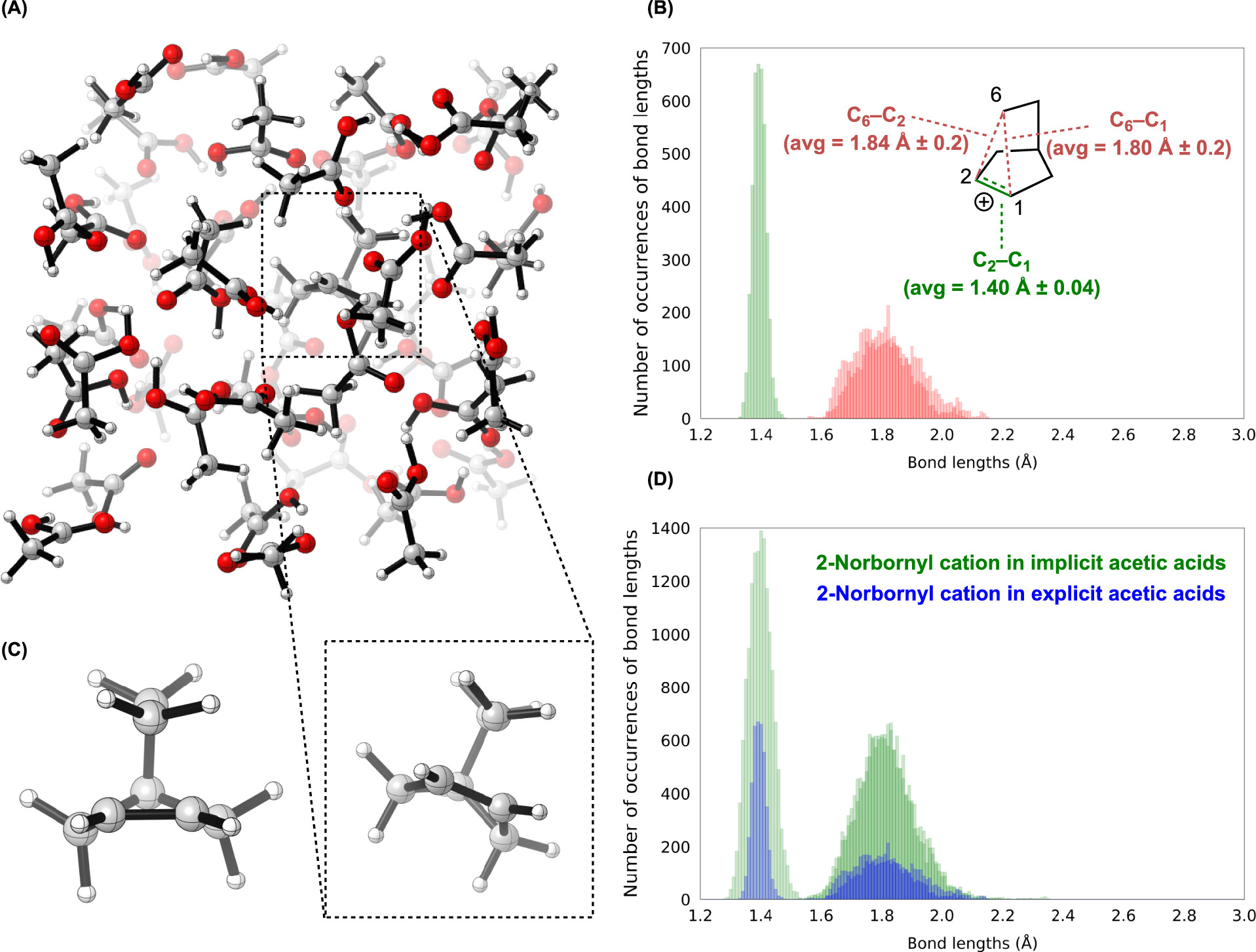

The nonclassical structure, “II” above, is a little tough to visualize as drawn. Here’s the computed structure at the B3LYP-D3BJ/6-31G(d) level of theory, which should be a bit clearer. You can click on atoms to see bond distances, angles, and dihedrals; notice that the C1–C2 bond above (C14–C18 in Rowan) is markedly shorter than a normal C–C bond, whereas the C1–C6 and C2–C6 bonds (C13–C14 and C14–C18 in Rowan) are quite long.

In the 1960s Winstein’s interpretation was challenged by another preeminent chemist, H.C. Brown, who argued that the data could adequately be explained by rapidly equilibrating classical carbocations. Brown suggested that most of the observations made by Winstein could be explained simply by the differing steric profiles of the exo and endo faces of the norbornyl cation: the endo face is more shielded, and so ionization is slowed (explaining the 350:1 exo/endo rates) and attack is disfavored (explaining why both isomers of sulfonate give exo product).

This began an incredibly contentious series of debates which dragged on for decades. Rather than attempt to wade through the resulting sea of publications, I’ll quote from an excellent 1983 review by Cheves Walling to give a sense for the magnitude of the controversy:

The debate [over the structure of the norbornyl cation] was vigorously pursued verbally in lectures, meetings, and seminars all over the U.S. and even abroad…. No one has ever counted the number of publications touching on the 2-norbornyl cation problem, but they include a number of reviews, chapters, and books, and a typcial [sic] research paper may well include references to over 100 others.

Walling’s review goes on to give an excellent overview of the various pieces of evidence employed by both sides of the debate, which I won’t summarize in full here.

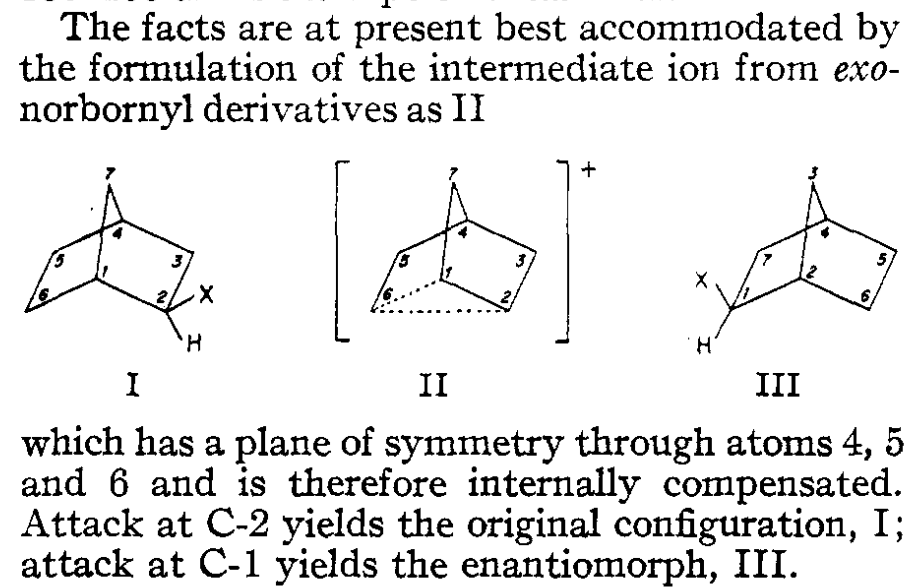

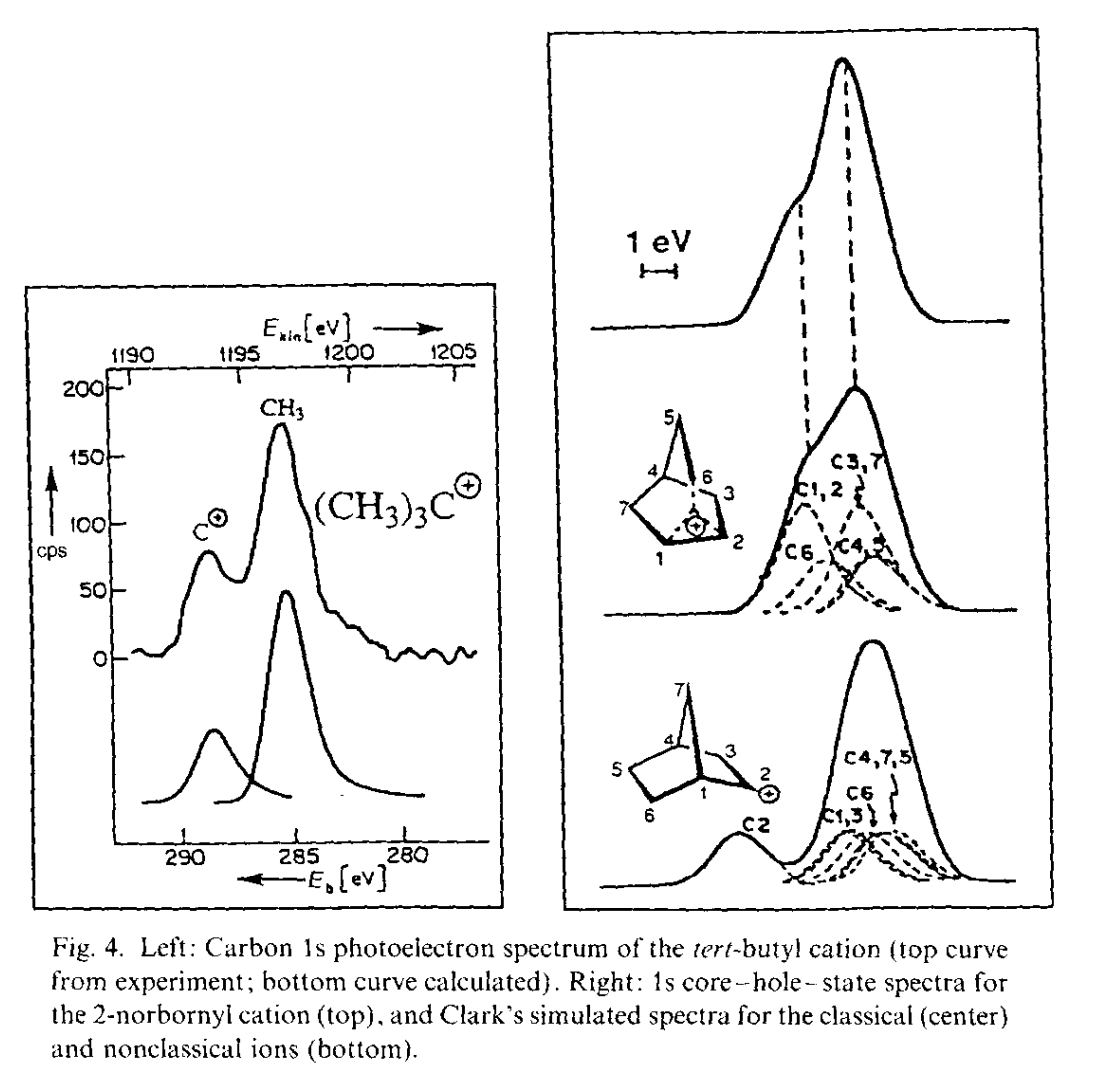

The most important data was obtained by George Olah and co-workers, who pioneered the use of superacidic media to generate stable solutions of carbocations which could be characterized spectroscopically. With Martin Saunders and others, Olah employed 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, IR spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and core electron spectroscopy to study low-temperature solutions of norbornyl cations: in all cases, the data supported Winstein’s proposed symmetric structure. (While equilibration occurring faster than the spectroscopic timescale could not be ruled out by Olah’s work, spectroscopic measurements all the way down to 5 K showed no detectable classical structures, indicating that any barrier to interconversion must be <0.2 kcal/mol.)

Note: On Twitter/X, Dan Singleton argues that the controversy was largely settled by 1982 and attributes this to the Saunders/Olah NMR experiments and Cyril Grob's work in this area, which I didn't mention. I appreciate the correction and welcome any further additions to the record.

Computational chemistry, which became able to tackle problems like this in the late 1980s and early 1990s, also supported the nonclassical structure of the norbornyl cation. A 1990 paper used HF/6-31G(d) calculations in Gaussian 86 to show that the symmetric structure was a minimum on the potential energy surface. Here’s a scan I ran at the B3LYP-D3BJ/6-31G(d) level of theory, showing that the energy increases as the “classical” C–C bond forms:

(This iframe doesn't work well on the phone - still a work in progress, sorry.)

Subsequent work has confirmed that Winstein was almost completely correct about the key issues. Most notably, a 2013 crystal structure from Karsten Meyer demonstrates that the norbornyl cation is indeed nonclassical in the ground state, leading Chemistry World to declare the mystery solved. Nevertheless, there’s still a little room for a classical cation supporter to doubt this result: crystal structures are snapshots of solid-state atomic configurations, while reactions occur in solution, where molecules are free to move around more. (In the Chemistry World article, Paul Schleyer predicts that Brown himself would have raised this objection.)

A paper from Ken Houk and co-workers, published a few days ago in JOC, addresses this issue by directly modeling the solvolysis process through ab initio molecular dynamics with explicit acetic acid solvent. In the solvolysis of the exo sulfonate, the authors find the nonclassical cation is formed on average within 9 femtoseconds of C–O bond cleavage, which is about as quickly as is physically possible. Once formed, the cation is entirely nonclassical: “classical 2-norbornyl cations are a negligible component of norbornyl cations in solution," thus addressing the last objection of classical cation partisans.

In contrast, Houk et al find that the endo sulfonate doesn’t form the nonclassical cation until about 81 fs after the C–O bond breaks, explaining the slower reaction rate: the transition state isn’t stabilized by σ-dissociation, and so is higher in energy. This is a nice example of the principle of nonperfect synchronization, which is explained concisely in this presentation.

What can modern scientists learn from the norbornyl cation controversy, besides the object-level fact that carbocations can exhibit nonclassical σ-delocalization?

It’s a good exercise to go back and read the early H.C. Brown papers in this area, like this account. Brown was an incredible scientist (the 1979 Nobel laureate in chemistry), and his data and reasoning are quite good; I find myself sympathizing with his viewpoint while reading his papers. Nevertheless, with the benefit of hindsight we know that he was wrong and Winstein was right. “Humility comes before honor.”

The argument over the norbornyl cation was ultimately settled only by the development of new techniques, like superacid chemistry, core electron spectroscopy, and high-level calculations. Now that we have these methods, it’s much easier to solve similar problems: if Winstein’s paper came out today, I doubt it would take more than a year or two to figure everything out.

This aligns nicely with what Freeman Dyson calls a “Galisonian” view of scientific progress, where scientific progress is driven not by ideas (the “Kuhnian” view) but by new tools and new data. In chemistry, at least, the tools-first view seems true to me—since 1950, it’s difficult to think of a development more important to organic chemistry than NMR spectroscopy, with flash column chromatography probably taking second place.

Here’s Walling again:

Since a significant fraction of the efforts of physical organic chemists was drawn into the problem [of the norbornyl cation], an unhappy consequence was a feeling on the part of many (including some of those concerned with the distribution of research funds) that physical organic chemistry was in danger of withdrawing into a world of its own.

As older scientists have explained to me, the norbornyl cation debacle scared a generation of chemists away from physical organic chemistry. The entire subfield became obsessed with a niche and somewhat irrelevant issue, while scientists in adjacent subfields looked on with bemusement and frustration. As a consequence, traditional physical organic chemistry is barely practiced today: few scientists have the skill or knowledge to conduct kinetic studies like those performed by Winstein, Brown, and others, and those still working in the area struggle to get funding or recognition (in the words of Dan Singleton, “sucks when you have to peddle your papers in cemeteries”).

(In a nice historical perspective, Stephen Weininger argues the norbornyl cation debate was “a hook on which to hang a much larger agenda,” fueled both by a UK/US divide and a deeper dispute about whether valence bond representations or molecular orbital representations of chemical structures were superior. If this is true, it was a self-defeating exercise by all involved.)

Scientists should be motivated by a search for truth, but also by the desire to improve the world. Usually these two aims go together: basic research without obvious societal implications often leads to unexpected and important findings, which is why the government supports science in the first place. But it’s possible to become so myopically focused on a single issue in the name of truth that one forgets about other goals, as arguably happened in the norbornyl cation imbroglio.

Controversy attracts attention: we’re drawn to it, against our better judgment, like moths to a flame. We have to be careful not to get captured by disputes that are, in the long run, not worth the effort.

Update 1/5/2024: some followup thoughts based on feedback from X.

Thanks to Eric Jacobsen for many conversations about the history of physical organic chemistry, Eugene Kwan for conversations about the principle of nonperfect synchronization, and to Ari Wagen for feedback on this post and six months of excellent front-end development for Rowan. Any errors are mine alone.