“Like arrows in the hand of a warrior are the children of one's youth.”

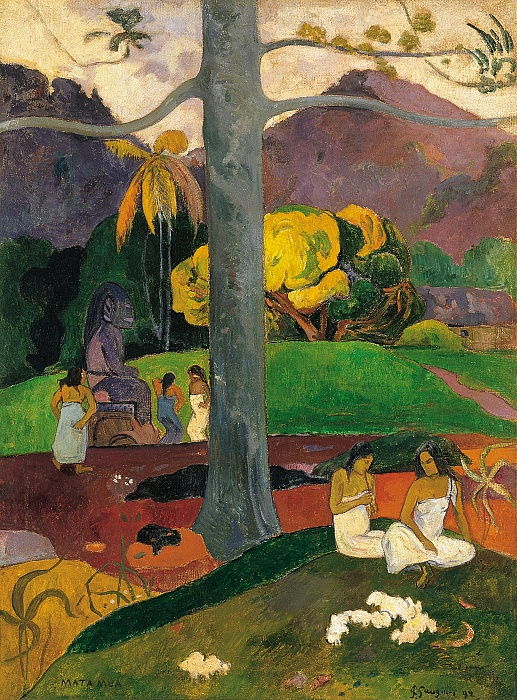

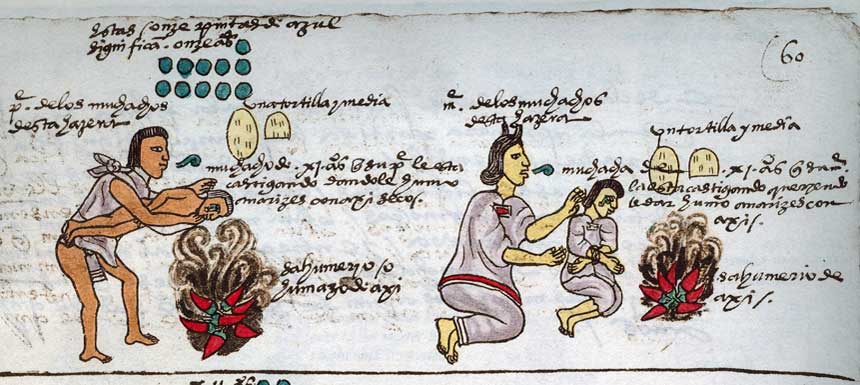

What if our most fundamental assumptions about parenting were wrong? That’s the question that Michaeleen Doucleff’s 2021 book Hunt, Gather, Parent tries to tackle. Hunt, Gather, Parent (henceforth HGP) documents Doucleff’s journey to “three of the world’s most venerable cultures”—the Maya, the Inuit, and the Hadzabe (in Tanzania)—to learn about how they parent their children, and offers helpful advice for parents envious of the kind, helpful, and responsible children she observes.

Doucleff’s writing hits some familiar beats: critiques of helicopter parenting, distrust of endless after-school activities, and laments about the atomization of our society (cf.). But there are plenty of unexpected insights too. I was convicted by her account of how Hadzabe children are given autonomy and responsibilities from a young age without being either ignored or micromanaged: her vision of a middle ground between K-selected “helicopter parents” and r-selected “free-range parents” was compelling.

There’s a lot to like about the parenting depicted in HGP. For instance, Doucleff highlights how toddlers’ innate eagerness to help is used by the Maya to build a culture of helpfulness (the virtue she calls acomedido) which lasts as they grow, whereas American parents generally disregard help from a toddler and thus teach kids that their help isn’t valued. On the other hand, I’m not compelled by her account of how the Inuit view conflict with their children:

Inuit see arguing with children as silly and a waste of time… because children are pretty much illogical beings. When an adult argues with a child, the adult stoops to the child’s level… During my three visits to the Arctic, I never once witness a parent argue with a child. I never see a power struggle. I never hear nagging or negotiating. Never.

I admit that getting into a shouting match with your toddler is pointless, but assuming that children are innately devoid of logic seems like an overreaction!

Astute readers might be getting bothered by now, though: why are the Maya—who ruled a swath of Central America for over a millennium—included in a book ostensibly about “hunter-gatherers and other indigenous cultures with similar values”? This highlights a deeper issue I have with HGP, which is that it partitions the world neatly into “Westerners” and “everyone else,” citing Joseph Heinrich’s The WEIRDest People in the World as its justification. While there are certainly many ways in which our own culture is distinct, ours is but one among many, and there’s plenty of cultural diversity about which HGP is silent.

For instance, Doucleff argues that in other cultures “parents build a relationship with young children… that’s based in cooperation instead of conflict, trust instead of fear.” I’m skeptical about this claim—what might we learn from some other non-WEIRD societies?

(Granted, these cultures aren’t “indigenous,” but then neither are the Maya.)

Doucleff’s focus on partitioning the world into “the West” and “the rest” blinds her to deeper and more interesting questions. The way we parent reflects our values—there are no perfect choices in parenting, just tradeoffs all the way down. Our culture’s valorization of grindset likely helps us instill ambition and a work ethic in our children, but also probably sets them up for depression and other issues down the road. Is this a good trade? Absent an ethical framework, it’s tough to say, but HGP doesn’t even acknowledge the question.

There’s a deeper truth here, which is that rejecting the status quo isn’t the same as proposing an alternative. It’s not unfair to read HGP as an account of Doucleff becoming redpilled on parenting and realizing that all her assumptions about how to raise her children might be wrong—but, like many of the newly redpilled, Doucleff lingers too long in her rebellion and doesn’t (in HGP) articulate a satisfying positive vision for what parenting should be. There are innumerable cultures out there, each of which doubtless parents in a different way, and choosing what practices to adopt from each tradition requires wisdom.

But these aren’t choices we should want Doucleff to make for us. In the introduction to HGP, Doucleff writes that “as we move outside the U.S., we’ll start to see the Western approach to parenting with fresh eyes,” and this seems true. HGP prompts us to reflect on the choices we make as parents and the ways in which we might choose differently, and even if you disagree with all of Doucleff’s advice it’s worth reading for this experience alone.

Thanks to my wife for recommending this book to me, and for helpful discussions.