Quantum computing gets a lot of attention these days. In this post, I want to examine the application of quantum computing to quantum chemistry, with a focus on determining whether there are any business-viable applications today. My conclusion is that while quantum computing is a very exciting scientific direction for chemistry, it’s still very much a realm where basic research and development is needed, and it’s not yet ready for substantial commercial attention.

Briefly, for those unaware, quantum computing revolves around “qubits” (Biblical pun intended?), quantum analogs of regular bits. They can be in the spin-up or spin-down states, much like bits can hold a 0 or a 1, but they also exhibit quantum behavior like superposition and entanglement.

Algorithms which run on quantum computers can exhibit “quantum advantage,” where for a given problem the quantum algorithm scales better than the classical algorithm, or “quantum supremacy,” where the quantum algorithm is able to tackle problems inaccessible to classical computers. Perhaps the best-known example of this is Shor’s algorithm, which enables integer factorization in polynomial time (in comparison to the fastest classical algorithm, which is sub-exponential).

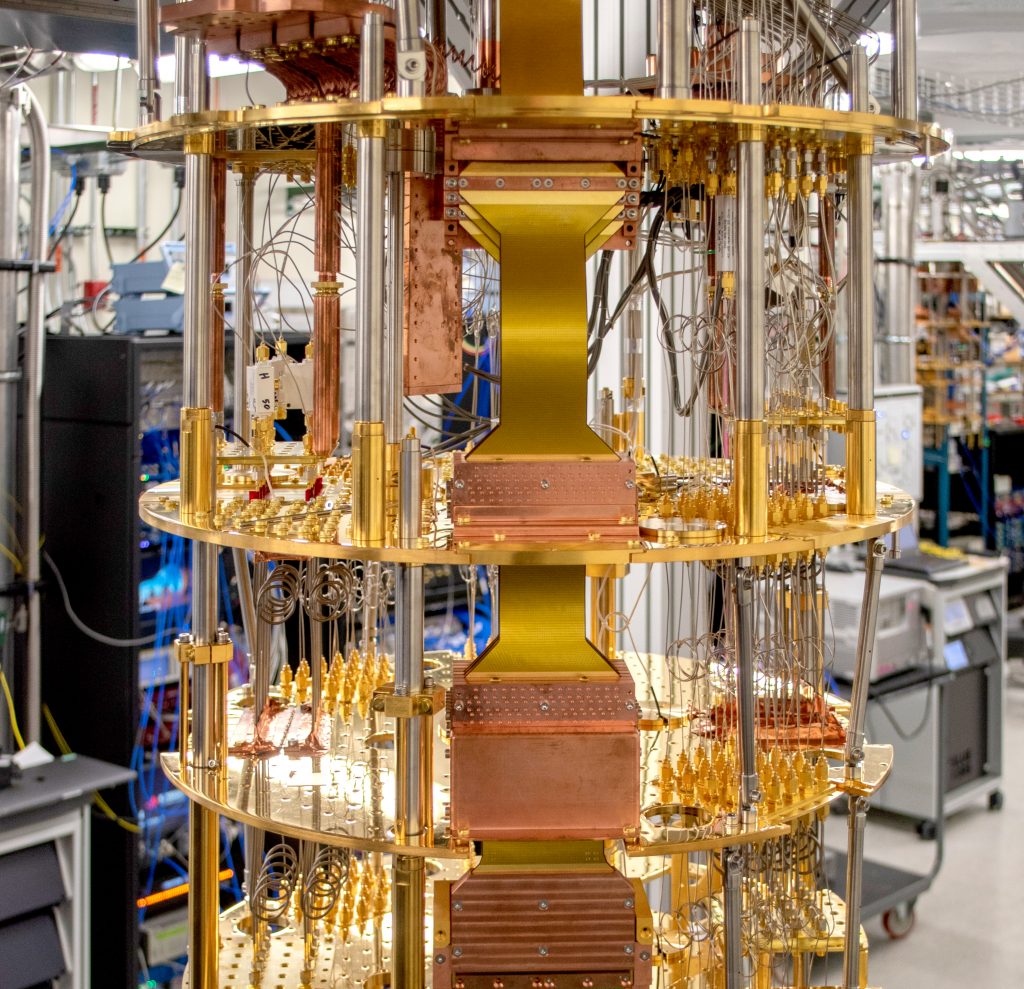

It’s pretty tough to actually make quantum computers in the real world, though. There are many different strategies for what to make qubits out of: isolated atoms, nitrogen vacancy centers in diamonds, superconductors, and trapped ions have all been proposed. The limited number of qubits accessible by state-of-the-art quantum computers, along with the high error rate and short decoherence times, means that practical quantum computation is very challenging today. These challenges are collectively described as “noisy intermediate-scale quantum”, or NISQ, the world we currently live in. Much effort has gone into trying to find NISQ-compatible algorithms.

Quantum chemistry, which revolves around simulating a quantum system (nuclei and electrons), seems like an ideal candidate for quantum computing. And indeed, many people have proposed using quantum computers for quantum chemistry, even going so far as to call chemistry the “killer app” for quantum computation.

Here are a few representative claims:

None of these claims are technically incorrect—there is a level of “full complexity” to caffeine which we cannot model today—but most of them are very misleading. Computational chemistry is doing just fine as a field without quantum computers; I don’t think there are any deep scientific questions about the nature of caffeine that depend on computing its exact electronic structure to the microHartree (competitions between physical chemists notwithstanding).

(Some other claims about quantum computing and chemistry border on the ridiculous: I’m not sure what to take away from this D-Wave press release which claims that their quantum computer can model 67 million solutions to the problem of “forever chemicals” in 13 seconds. Dulwich Quantum Computing, on Twitter/X, does an excellent job of cataloging such malfeasances.)

Nevertheless, there are many legitimate and exciting applications of quantum computing to chemistry. Perhaps the best-known is the variational quantum eigensolver (VQE), developed by Alán Aspuru-Guzik and co-workers in 2014. The VQE is a hybrid quantum/classical algorithm suitable for the NISQ era: it takes a Hartree–Fock calculation as the starting point, and then minimizes the energy by optimizing the system classically while evaluating the energy with a quantum computer. (If you want to learn more, there are a number of easy-to-read introductions to the VQE: here’s one from Joshua Goings, and here’s another from Pennylane.)

Another approach, more suitable for fault-tolerant quantum computers with large numbers of qubits, is quantum phase estimation. Quantum phase estimation, explained nicely by Pennylane here, works like this: given a unitary operator and a state, the state is projected into an eigenstate and the corresponding eigenvalue is returned. (It’s not just projected onto an eigenstate randomly; the probability of returning a given eigenstate is proportional to the overlap with the input state.) This might sound abstract, but the ground-state energy of a molecule is just the smallest eigenvalue of its Hamiltonian, so this provides a route to get exact ground-state energies, assuming we can generate good enough initial states (again, typically a Hartree–Fock calculations).

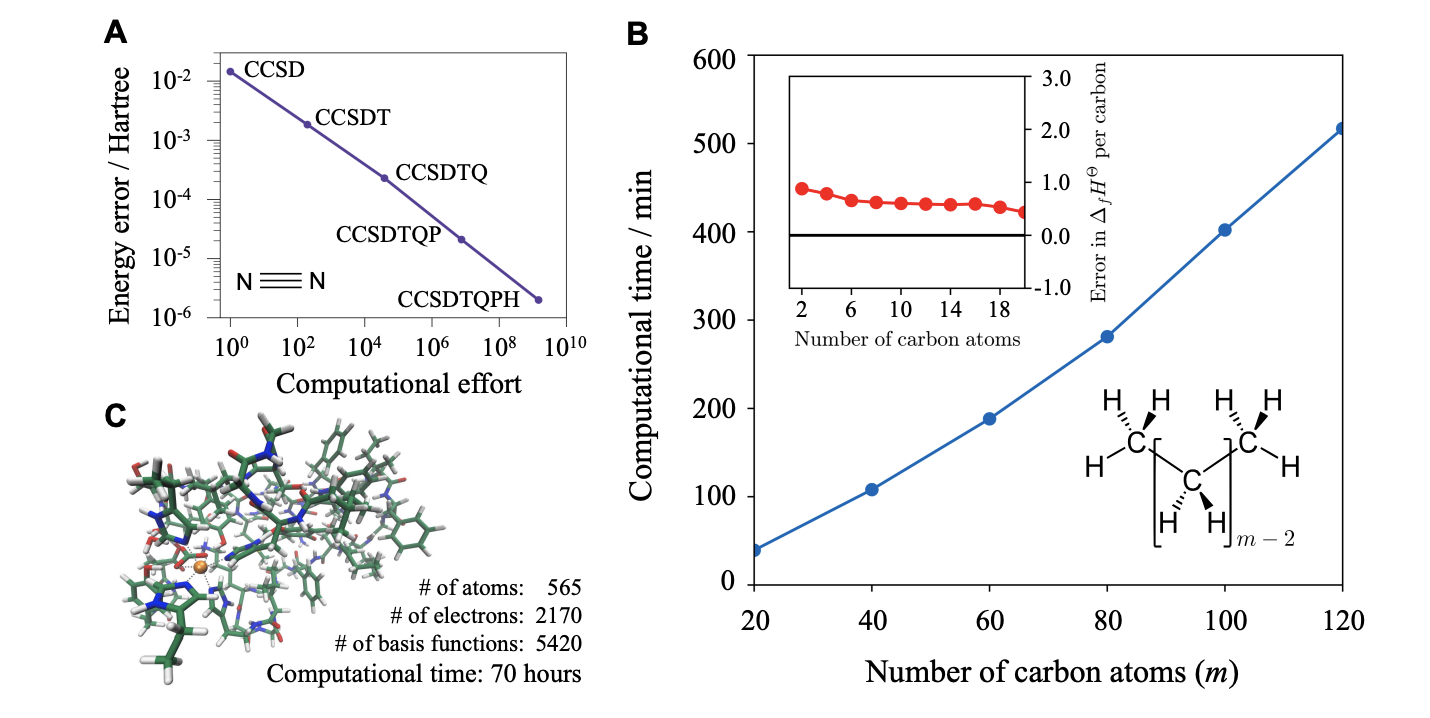

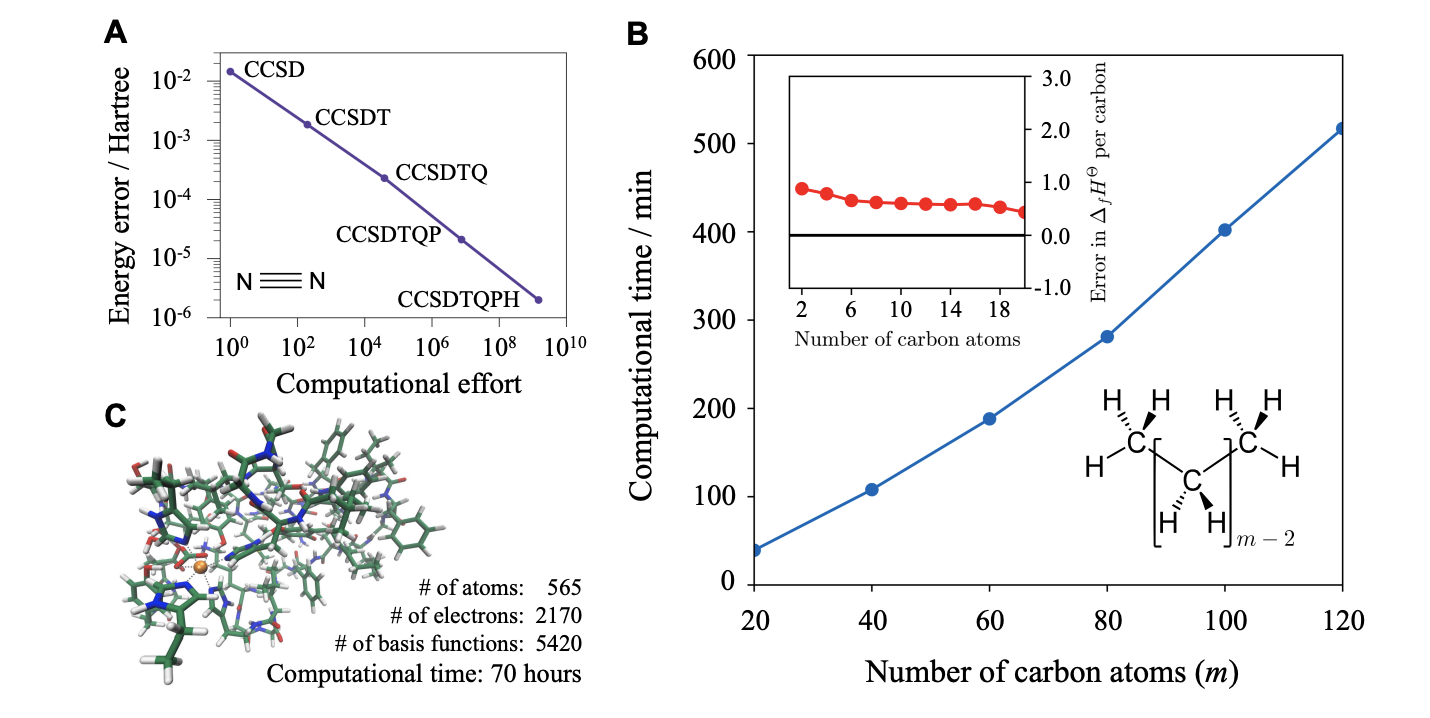

Both of these methods are pretty exciting, since full configuration interaction (the “correct” classical way to get the exact ground-state energy) typically has an O(N!) cost, making it prohibitively expensive for anything larger than, like, N2. Further work has built on these ideas: I don’t have the time or skillset to provide a full review of the field, although I’ll note this work from Head-Gordon & friends and this work from Joonho Lee. (These reviews provide an excellent overview of different algorithms; I’ll discuss it later on.)

Based on the above description, one might reasonably assume that quantum computers offer some sort of dramatic quantum advantage relative to their classic congeners. Recent work from Garnet Chan (and many coworkers) challenges this assumption, though:

…we do not find evidence for the exponential scaling of classical heuristics in a set of relevant problems. …our results suggest that without new and fundamental insights, there may be a lack of generic EQA [exponential quantum advantage] in this task. Identifying a relevant quantum chemical system with strong evidence of EQA remains an open question.

The authors make many interesting points. In particular, they point out that physical systems seem to exhibit locality, i.e. if we’re trying to describe some system embedded in a larger environment to a given accuracy, then there’s some distance beyond which we can ignore the larger environment. This means that there are almost certainly polynomial-time classical algorithms out there for all of computational chemistry, since at some point increasing system size won’t slow our computations down any more.

This might sound abstract, but the authors point out that coupled-cluster theory, which can (in principle) be extended to arbitrary levels of precision, can be made to take advantage of locality and scale linearly with increasing system size or increasing levels of accuracy. Although such algorithms aren’t known for strongly correlated systems, like metallic systems, Chan and co-workers argue based on analogy to strongly correlated model systems that analogous behavior can be expected.

The above paper is making a very specific point—that exponential quantum advantage is unlikely—but doesn’t address whether weaker versions of quantum advantage are likely. Could it still be the case that quantum algorithms exhibit polynomial quantum advantage, e.g. scaling as O(N) while classical algorithms scale as O(N2)?

Another recent paper, from scientists at Google and QSimulate, addresses this question by looking at the electronic structure of various iron complexes derived from cytochrome P450. They find that there’s some evidence that quantum computers (using quantum phase estimation) will be able to outcompete the best classical methods today (CCSD(T) and DMRG), but it’ll take a really big quantum computer:

Most notably, under realistic hardware configurations we predict that the largest models of CYP can be simulated with under 100 h of quantum computer time using approximately 5 million qubits implementing 7.8 × 109 Toffoli gates using four T factories. A direct runtime comparison of qubitized phase estimation shows a more favorable scaling than DMRG, in terms of bond dimension, and indicates future devices can potentially outperform classical machines when computing ground-state energies. Extrapolating the observed resource estimates to the full Cpd I system and compiling to the surface code indicate that a direct simulation of the entire system could require 1.5 trillion Toffoli gates—an unfeasible number of Toffoli gates to perform.

(A Toffoli gate is a three-qubit operator, described nicely here.)

Given that the largest quantum computer yet built is 433 qubits, it’s clear that there’s a lot of work left to do until we can use quantum computers to inaugurate “a new era of discovery in chemistry.”

A recent review agrees with this assessment: the authors write that “there is currently no evidence that heuristic NISQ approaches [like VQE] will be able to scale to large system sizes and provide advantage over classical methods,” and conclude with this paragraph:

Solving the electronic structure problem has repeatedly been identified as one of the most promising applications for quantum computers. Nevertheless, the discussion above highlights a number of challenges for current quantum approaches to become practical. Most notably, after accounting for the approximations typically made (i.e. incorporating the cost of initial state preparation, using nonminimal basis sets, including repetitions for correctness checking and sampling a range of parameters), a large number of logical qubits and total T/Toffoli gates are required. A major difficulty is that, unlike problems such as factoring, the end-to-end electronic structure problem typically requires solving a large number of closely related problem instances.

An important thing to note, which the above paragraph alludes to, is that the specific quantum algorithms discussed here don't actually make quantum chemistry faster than today’s methods—they typically rely on a Hartree–Fock ansatz, which is about the same amount of work as a DFT calculation. Since it's likely that proper treatment of electron correlation will require a sizable basis set, much like we see with coupled-cluster theory, we can presume that quantum methods would be slower than most DFT methods (even assuming that the actual quantum part of the calculation could be run instantly).

This ignores the fact that the quantum methods would of course give much better results—but an uncomfortable truth is that, unlike one might think from the exuberant press releases quoted above, classical algorithms generally do an exceptional job already. Most molecules are very simple from an electronic structure perspective: static electron correlation is pretty rare, and linear scaling CCSD(T) approaches are widely available and very effective (e.g.). There’s simply no need for FCI-quality results for most chemical problems, random exceptions notwithstanding.

(Aspuru-Guzik and co-workers agree; in a 2020 review, they state that they “do not expect [HF and DFT] calculations to be replaced by those on quantum computers, given the large system sizes that are simulated,” suggesting instead that quantum computers might find utility for statically correlated systems with 100+ spin orbitals)

A related point I made in a recent essay/white paper for Rowan is that quantum chemistry, at least as it’s applied to drug discovery, is limited not by accuracy but by speed. Existing quantum chemistry methods are already far more accurate than state-of-the-art drug discovery methods; replacing them with quantum computing-based approaches is like worrying about whether to bring a Lamborghini or a Formula 1 car to a go-kart race. It’s almost certain that there’s some way that “perfect” electronic structure calculations could be useful in drug design, but it’s hardly trivial to figure out how to turn a bunch of VQE calculations into a clinical candidate.

Other fields, like materials science, seem to be more limited by inaccuracies in theory—modeling metals and surfaces is really hard—but the Hartree–Fock ansatz is also hard here, and there are fewer commercial precedents for computational chemistry in general. To my knowledge, the Hartree–Fock starting point alone is a terrific challenge for a system like e.g. a cube of 10,000 metal atoms, which is why so many materials scientists avoid exact exchange and stick to local functionals. (I don't know much about computations on periodic systems, though, so correct me if this is wrong!) Using quantum computing to design superconducting materials probably won’t be as easy as it seems on Twitter/X.

So, while quantum computing is a terrifically exciting direction for computational chemistry in a scientific sense, I’m not sure it’s yet investable in a business sense. I don’t mean to belittle all the great scientific work being done in this field, in the papers I’ve referenced above and in many others. The point I’m trying to make here—that this field isn’t mature enough for actual commercial utility—could just as easily be made about ML in the 2000s, or any other number of promising but pre-commercial technologies.

I’ll close by noting that it seems like markets are coming around to this perspective, too. Zapata Computing, one of the original “quantum computing for chemistry” companies, recently pivoted to… generative AI, going public via a SPAC with Andretti (motorsport), and IonQ recently parted ways with its CSO, who is going back to his faculty job at Duke. We’ll see what happens, but progress in hardware has been slow, and it’s likely that it’ll be years yet until we can start to perform practical quantum chemical calculations on quantum computers.