Recently in off-blog content: I coauthored an article with Eric Gilliam on how LLMs can assist in hypothesis generation and help us all become more like Sharpless. Check it out!

The Pauling model for enzymatic catalysis states that enzymes are “antibodies for the transition state”—in other words, they preferentially bind to the transition state of a given reaction, rather than the reactants or products. This binding interaction stabilizes the TS, thus lowering its energy and accelerating the reaction.

This is a pretty intuitive model, and one which is often employed when thinking about organocatalysis, particularly noncovalent organocatalysis. (It’s a bit harder to use this model when the mechanism changes in a fundamental way, as with many organometallic reactions.) Many transition states have distinctive features, and it’s fun to think about what interactions could be engineered to recognize and stabilize only these features and nothing else in the reaction mixture.

(For instance, chymotrypsin contains a dual hydrogen-bond motif called the “oxyanion hole” which stabilizes developing negative charge in the Burgi–Dunitz TS for alcoholysis of amides. The negative charge is unique to the tetrahedral intermediate and the high-energy TSs to either side, so reactant/product inhibition isn’t a big issue. This motif can be mimicked by dual hydrogen-bond donor organocatalysts like the one my PhD lab specialized in.)

The downside of this approach to catalyst design is that each new sort of reaction mechanism requires a different sort of catalyst. One TS features increasing negative charge at one place, while another features increasing positive charge at another, and a third is practically charge-neutral the whole way through. What if there were some feature that was common to all transition states?

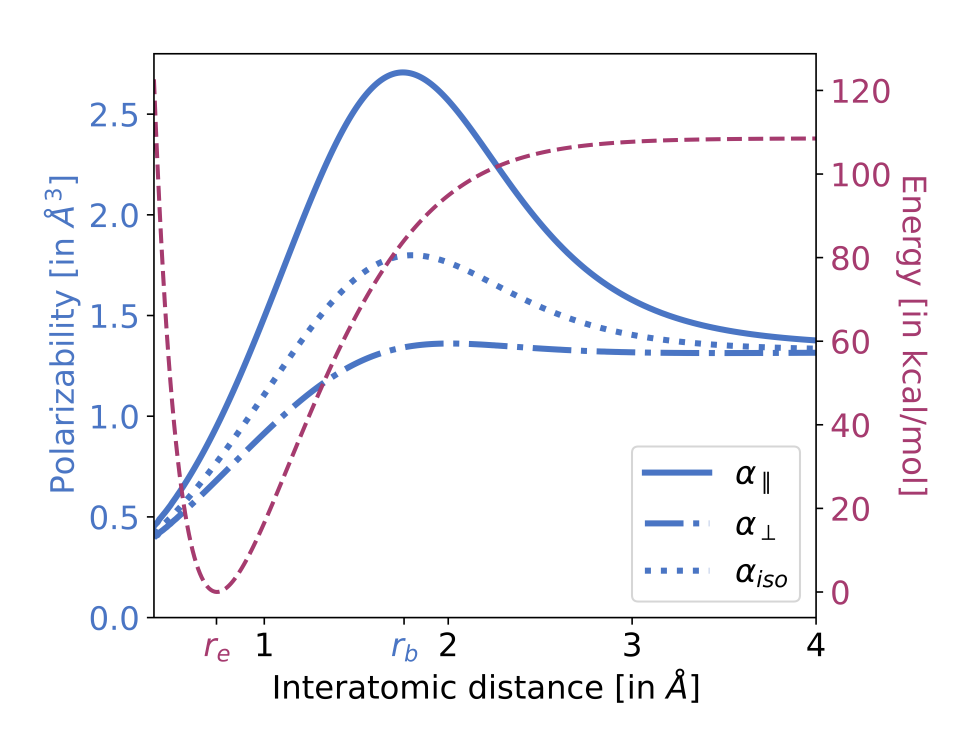

A recent preprint from Diptarka Hait and Martin Head-Gordon suggests an interesting answer to this question: polarizability. (Diptarka, despite just finishing his PhD, is a prolific scientist with a ton of different interests, and definitely someone to keep an eye on.) The authors tackle the question of when precisely a stretching bond can be considered “broken.” An intuitive answer might be “the transition state,” but as the paper points out, plenty of bond-breaking potential energy surfaces lack clear transition states (e.g. H2, pictured below in red).

Instead, the authors propose that polarizability is a good way to study this question. As seen in the following graph, polarizability (particularly α||, the component parallel to the bond axis) first increases as a bond is stretched, and then decreases, with a sharp and easily identifiable maximum about where a bond might be considered to be broken. This metric tracks with the conventional PES metric in cases where the PES is well-defined (see Fig. 5), which is comforting. Why does this occur?

The evolution of α [polarizability] can be rationalized in the following manner. Upon initially stretching H2 from equilibrium, the bonding electrons fill up the additional accessible volume, resulting in a more diffuse (and thus more polarizable) electron density. Post bond cleavage however, the electrons start localizing on individual atoms, leading to a decrease in polarizability.

In other words, electrons that are “caught in the act” of reorganizing between different atoms are more polarizable, whereas electrons which have settled into their new atomic residences are less polarizable again.

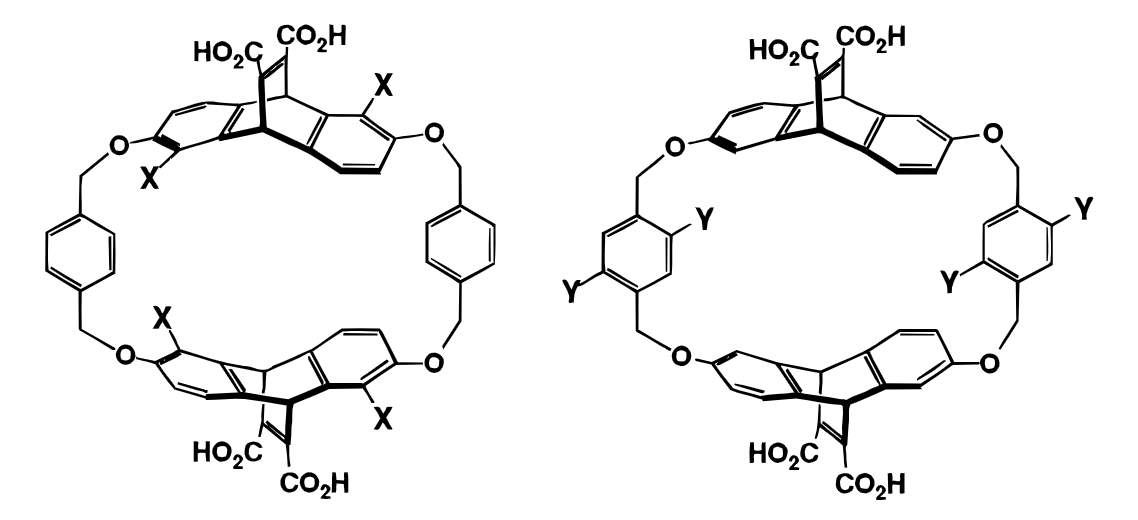

This is cool, but how can we apply this to catalysis? As it happens, there are already a few publications (1, 2) from Dennis Dougherty and coworkers dealing with exactly this question. They show that cyclophanes are potent catalysts for SN2-type reactions that both create and destroy cations, and argue that polarizability, rather than any charge-recognition effect, undergirds the observed catalysis:

Since transition states have long, weak bonds, they are expected to be more polarizable than ground-state substrates or products. The role of the host is to surround the transition state with an electron-rich-system that is polarizable and in a relatively fixed orientation, so that induced dipoles in both the host and the transition state are suitably aligned… Note that in this model, it is not sufficient that polarizability contributes to binding. Polarizability must be more important for binding transition states than for binding ground states. Only in this way can it enhance catalysis.

To defend this argument, the authors prepare a series of variously substituted cyclophanes, and show that while Hammett-type electronic tuning of the aryl rings has relatively small effects, adding more heavy atoms always increases the rate, with the biggest effect observed with bromine (the heaviest element attempted). Heavier atoms are more polarizable, so this supports the argument that polarizability, rather than any specific electrostatic effect, is responsible for catalysis.

The Dougherty work is performed on a very specific model system, and the absolute rate accelerations seen aren’t massive (about twofold increase relative to the protio analog), so it’s not clear that this will actually be a promising avenue for developing mechanism-agnostic catalysts.

But I think this line of research is really interesting, and merits further investigation. Pericyclic reactions, which involve large electron clouds and multiple forming–breaking bonds and often feature minimal development of partial charges, seem promising targets for this sort of catalysis—what about the carbonyl–ene reaction or something similar? The promise of new catalytic strategies that complement existing mechanism-specific interactions is just too powerful to leave unstudied.

Thanks to Joe Gair for originally showing me the Dougherty papers referenced.