I first encountered organic chemistry on Wikipedia, my freshman year of high school. The complexity and arcanity of the field instantly attracted me: here was something interesting that I didn’t know about and which didn’t require years of mathematical training to approach (unlike most of physics).

I soon started reading about organic chemistry more and more, albeit with no rhyme or reason to my study. I didn’t know what the good textbooks were, what order to study things in or which concepts ought to be understood in depth before progressing further. Organic chemistry was just a “glass bead game” to me, an art of symbols devoid of any real-world representations. But enthusiasm can sometimes suffice where wisdom is lacking.

With the support of a teacher and a half-dozen friends who also wanted to learn more organic chemistry, we started a little independent study. We met in a closet and read a textbook, worked through the problems, and our teacher wrote us tests. We eventually managed to get through all of Paula Bruice, although various misconceptions (and mispronunciations) stayed with me until I took Movassaghi’s course at MIT.

But in high school we had no lab, and thus no practical knowledge. We split into two groups and tried to come up with experiments for ourselves, but the results were dismal. Here’s the procedure (copied verbatim) for the one and only reaction we ran, synthesis of nitrobenzene via nitration of benzene, which was to be the first step in a multistep synthesis of Kevlar:

In a 250 mL beaker, dissolve benzene in a solution of concentrated H2SO4 of twice its volume. Use an ice-salt bath to bring this solution to 0 °C or below, and use a Pasteur pipette to slowly add a 1:1 solution of HNO3 and H2SO4 (be sure to keep the solution below 15 degrees Celsius at all times, as the reaction is strongly exothermic). Once all the solution has been added, warm it to room temperature and allow it to sit for 15 minutes.

Pour the solution over 50 g of crushed ice in a 250 mL beaker. Once the ice has melted, isolate the product via vacuum filtration via a Buchner funnel and rinse it twice with water and twice with methanol. Recrystallize in a solution of methanol.

The astute observer will notice that there aren’t very many details here. How much benzene? How much nitric acid? We didn’t have the glassware mentioned above—neither a beaker nor a Buchner funnel. And, perhaps most damningly, the procedure calls for isolation by filtration, challenging since nitrobenzene is a liquid at room temperature.

Despite these problems, we successfully ran this reaction (open to air, not in a fume hood), and obtained the product. I vividly recall the yellow bubbles of nitrobenzene floating to the top of the vial, and the smell of cherries that filled the room, a smell that returns to me in Proustian fashion from time to time when using certain reagents. We didn’t have a separatory funnel (or we didn’t know how to use it if we did), so we fished some of the nitrobenzene out with a Pasteur pipette and threw the rest away.

A little bit of knowledge would have served us well, as would have gloves and a fume hood. Here’s Wikipedia:

Prolonged exposure [to nitrobenzene] may cause serious damage to the central nervous system, impair vision, cause liver or kidney damage, anemia and lung irritation. Inhalation of vapors may induce headache, nausea, fatigue, dizziness, cyanosis, weakness in the arms and legs, and in rare cases may be fatal…

Nitrobenzene is considered a likely human carcinogen by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, and is classified by the IARC as a Group 2B carcinogen which is "possibly carcinogenic to humans".

Indeed, a coworker of mine would later be sent to the hospital after spilling nitrobenzene on herself. Surprisingly, my group’s experiment still ended up being the safer one—the lab portion of our course was disbanded the following day after my classmates caused an explosion with thionyl chloride.

I was fortunate enough to land a summer research internship in the Sessler lab at UT the following summer, and I started studying chemistry in earnest: column chromatography, Anslyn/Dougherty, NMR spectroscopy, and all the rest. I remember the first reaction I ran at UT: retro-Friedel–Crafts dealkylation of a calix[4]arene, using about 10 g each of phenol and aluminum(III) chloride. The brutal physicality of lab work was a nice contrast to the gnosticism of software (where I’d worked previously), and I was hooked.

I’ll fast-forward through the more recent parts of my chemical career: I went to MIT and joined the Imperiali lab to work on essentially a medicinal chemistry project: hit-to-lead optimization, featuring lots of de novo heterocycle synthesis. I got to cook reactions in molten urea, quench 500 mL of phosphorus oxychloride at a time, and even design new routes (with a little oversight from my postdoc). It was awesome.

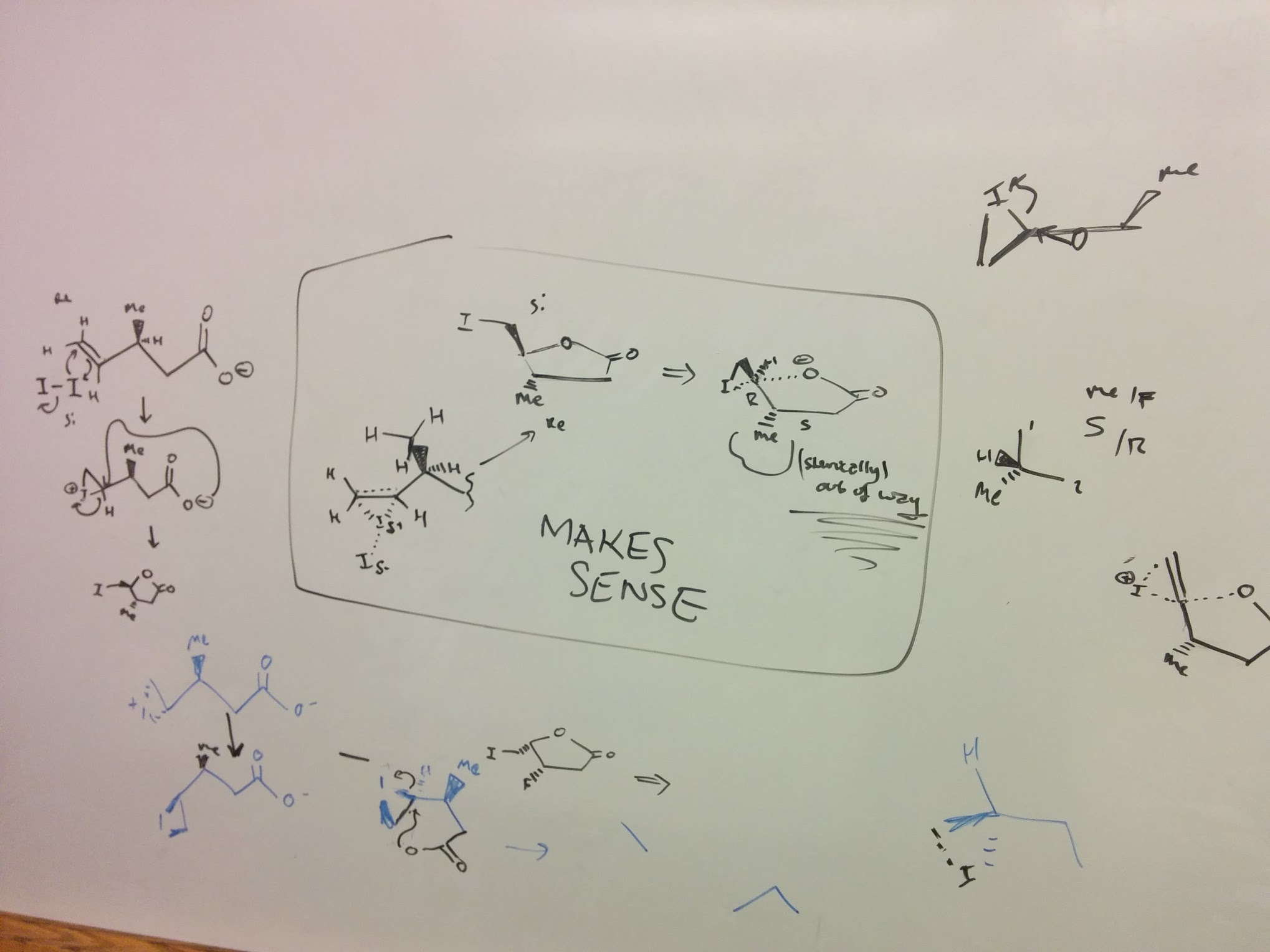

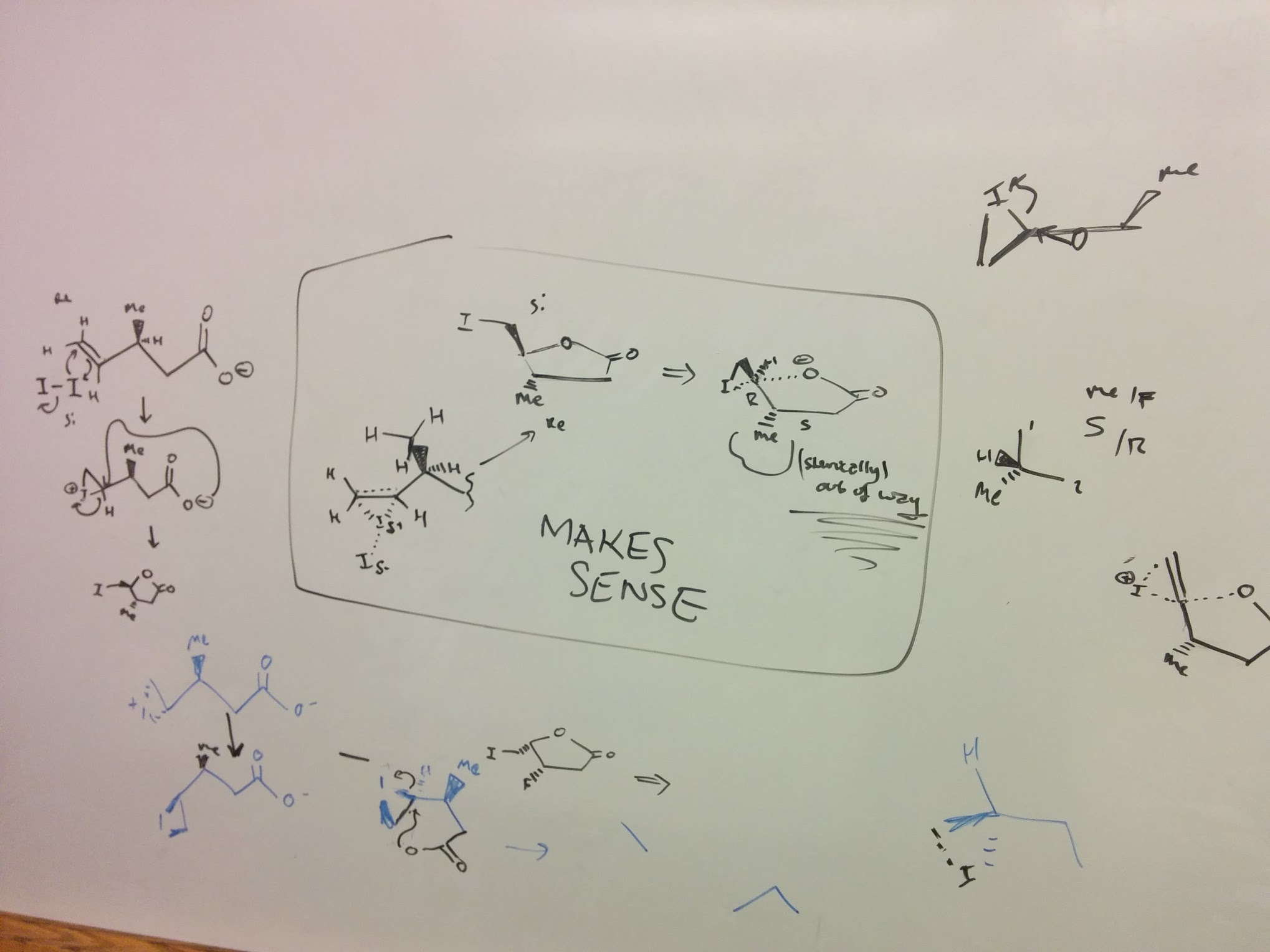

After three semesters, I got tired of my cross couplings mysteriously failing and joined the Buchwald lab, where I learned how to do chemistry more carefully: handling air-sensitive materials with a Schlenk line or in the glovebox, not “as fast as possible.” My tenure in the Buchwald lab also introduced me to the importance of computations, which became a key part of my doctoral work, particularly when we were sent home in March of my first year. COVID gave me the opportunity to pursue some software engineering projects that I wouldn’t have had time to work on otherwise (like cctk and presto), and simulation started to take up more and more of my time and intellectual bandwidth.

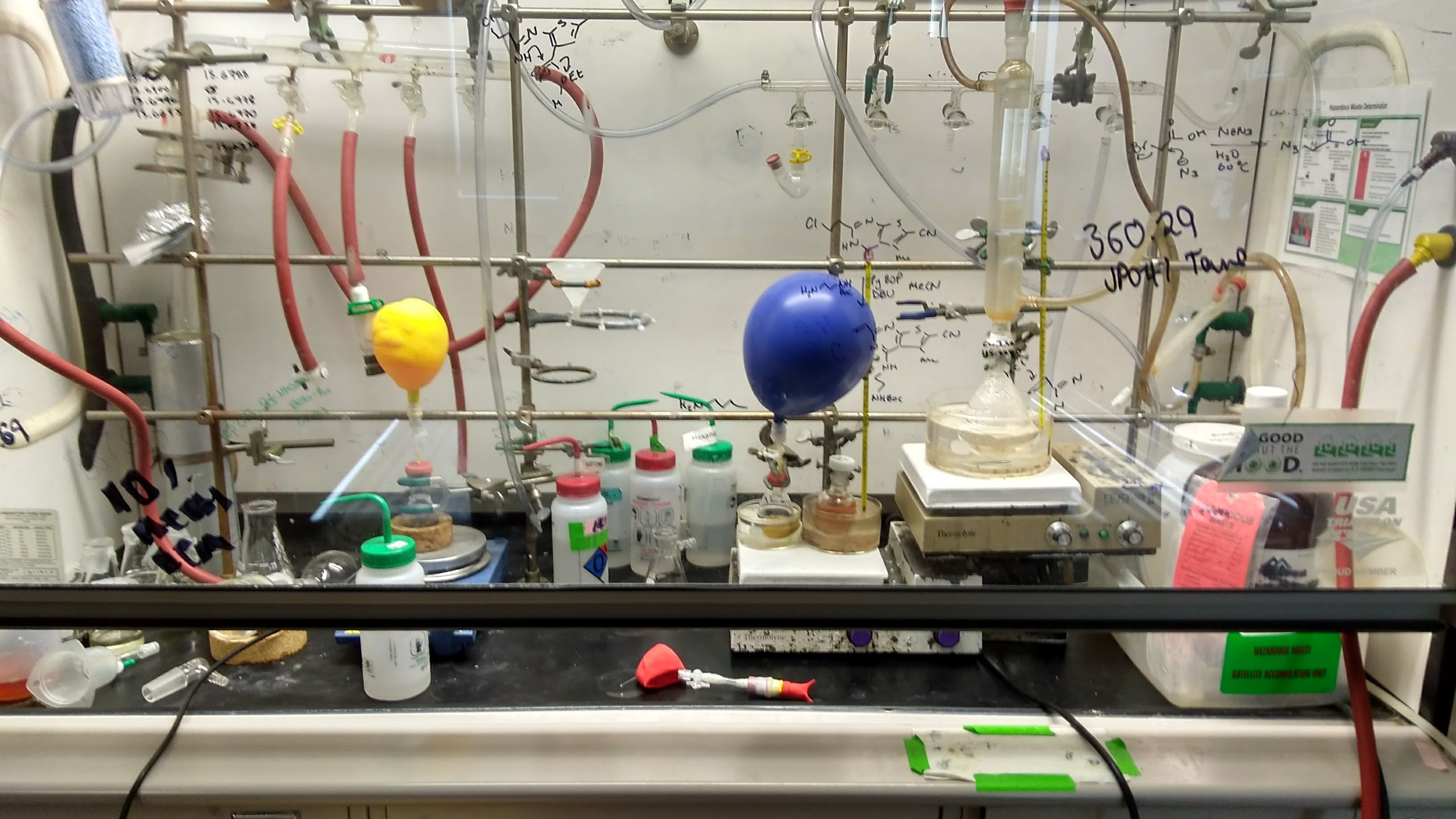

I defended my dissertation on June 5th, and cleaned out my hood last week. For the foreseeable future, I’ll be a purely computational chemist—computation is advancing quickly, and I think that’s where I have the most to offer the field right now. But I’ll miss the sights and sounds of the lab. There’s a satisfaction to making a new molecule and holding the final product in your hands: the knowledge that you’ve reshaped this little corner of reality through your own actions, and that this particular arrangement of matter has never existed before.

And simulation is, at the end of the day, only useful insofar as it helps us make real molecules. There may be people who wish to model reactions purely for the sake of modeling them, but I am not one of them. What drew me to simulation initially, and what still attracts me to the field today, is its potential to help experimental scientists do their work faster and better. It was easy for me to ensure that this was true when I was both doing the experiments and running the simulations; my incentives were aligned properly. It will be harder in the future.

There’s a seductive appeal in leaving lab work behind altogether, too, and one that’s dangerous. Any experimentalist who’s worked with a computational collaborator knows that nothing ever works precisely as modeled. There are untold depths of chemical behavior still inaccessible to the idealized world of simulation, and it’s all too easy for computational chemists just to look the other way. Life is easier when you don’t have to deal with sludgy workups or poorly soluble intermediates, but they don’t go away just because you can’t model them by DFT—reality has a way of keeping us honest that simulations frequently lack.

So, although I bid lab farewell at this point in my career, it’s a bittersweet parting. I hope to return someday; only time will tell.

Thanks to Jacob Thackston for reading a draft of this piece.