Not Boring recently published a panegyric about Varda, a startup that’s trying to create “space factories making drugs in orbit.” When I first read this description, alarm bells went off in my head—why would anyone try to make drugs in space? Nevertheless, there’s more to this idea than I initially thought. In this piece, I want to dig a little deeper into the chemistry behind Varda, and discuss some potential advantages and challenges of the approach they’re exploring.

Much of my confusion was quickly resolved by realizing that Varda is not actually “making drugs in orbit,” or not in the way that an organic chemist would interpret that sentence. Varda’s proposal is actually much more specific: they aim to crystallize active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs, i.e. finished drug molecules) in microgravity, allowing them to access crystal forms and particle size distributions which can’t be made under terrestrial conditions. To quote from their website:

Varda’s microgravity platform is grounded in decades of proven research conducted on NASA’s space stations. By eliminating factors such as natural convection and sedimentation, processing in a microgravity environment provides a unique path to formulating small molecules and biologics that traditional manufacturing processes cannot address. The resulting tunable particle size distributions, more ordered crystals, and new forms can lead to improved bioavailability, extended shelf-life, new intellectual property, and new routes of administration.

Crystallization is an excellent target for a new and expensive manufacturing process because it’s at once very important and very hard to control. The goal of crystallization is to grow crystals of a given compound, fitting the component molecules together into a perfect lattice that excludes impurities and can be easily handled. To the best of my knowledge, almost every small-molecule API is crystallized at one stage or another; it’s the best way to ensure that the material is extremely pure.

(Crystallizing proteins for administration is less common, since proteins are really difficult to crystallize, but it’s not unheard of—insulin is often administered subcutaneously as a microcrystalline suspension, which allows higher concentrations to be accessed without excessive viscosity.)

But crystallization is also something we can’t really control. We can’t physically put molecules into a lattice or force them to adopt ordered configurations; all we can do is dissolve them in some mixture, tweak the conditions a little bit, and hope that crystals form. Thus, finding good crystallization conditions basically amounts to randomly screening solvents and additives, leaving the solutions for a long time, and checking to see if crystals grow. In the words of Derek Lowe:

I'd like to open up the floor for nominations for the Blackest Art in All of Chemistry. And my candidate is a strong, strong contender: crystallization. When you go into a protein crystallography lab and see stack after stack after stack of plastic trays, each containing scores of different little wells, each with a slight variation on the conditions, you realize that you're looking at something that we just don't understand very well.

Why does microgravity matter for crystallization? Not Boring says that crystallization occurs “at the mesoscopic scale, the length scale on which objects are larger than nanoscale (on the order of atoms and molecules) but still small enough that quantum mechanical or other non-trivial ‘microscopic’ behavior becomes apparent.” I found this answer a little confusing—doesn’t crystallization begin on the nanoscale and end on the macroscopic scale?

Clearer to me was the explanation from a 2001 review by Kundrot and co-workers:

In zero gravity, a crystal is subject to Brownian motion as on the ground, but unlike the ground case, there is no acceleration inducing it to sediment [fall out of solution]. A growing crystal in zero gravity will move very little with respect to the surrounding fluid. Moreover, as growth units leave solution and are added to the crystal, a region of solution depleted in protein is formed. Usually this solution has a lower density than the bulk solution and will convect upward in a 1g field as seen by Schlerien photography (Figure 1). In zero gravity, the bouyant [sic] force is eliminated and no bouyancy-driven convection occurs. Because the positions of the crystal and its depletion zone are stable, the crystal can grow under conditions where its growing surface is in contact with a solution that is only slightly supersaturated. In contrast, the sedimentation and convection that occur under 1g place the growing crystal surface in contact with bulk solution that is typically several times supersaturated. Lower supersaturation at the growing crystal surface allows more high-energy misincorporated growth units to disassociate from the crystal before becoming trapped in the crystal by the addition of other growth units…

In short, promotion of a stable depletion zone in microgravity is postulated to provide a better ordered crystal lattice and benefit the crystal growth process.

To summarize, microgravity serves to immobilize the crystal with respect to the surrounding solution, preventing convection or sedimentation from bringing highly concentrated solutions into contact with the crystal. This slows crystal growth, which might sound bad but is actually really good: in general, the slower a crystal grows, the higher its purity. (See also this 2015 article for further discussion.)

What practical impact does this have? In most cases, crystals grown in space are better than their terrestrial congeners by a variety of metrics: larger, structurally better, and more uniform. To quote from the Not Boring piece:

Doing crystallization in space is like adding a gravity knob to your instrument—it opens up regions of process design space that would otherwise be inaccessible. Importantly, after the crystallization occurs in space, the drug retains its solid state upon re-entry. Manufacture in space; use on earth.

This is why pharma is going to space to experiment with a wide range of medicines. Formulations made in microgravity could open the door to improvements in drug shelf life, bioavailability, IP expansion, and even better approaches to drug delivery…

To date, there has been a major disconnect between microgravity research and manufacturing. While it’s been possible to hitch a ride to the ISS and collaborate with NASA on PCG experiments, there is no existing commercial offering to actually manufacture drugs in space. Merck used their research results on Keytruda® crystallization to tinker with their terrestrial approaches to formulation. What if they could actually just manufacture the crystals they discovered in microgravity at commercial scale?

This is Varda’s mission—to make widespread research and manufacturing in microgravity a reality.

One concern I have is that to date, the vast majority of space-based crystallization has been aimed at structural biology (elucidating the structure of a protein via crystallography), which only takes one crystal, one time. What Varda is aiming to do is preparative crystallography: crystallizing proteins and small molecules to isolate large quantities of them. Both processes obviously involve growing crystals, but otherwise they’re pretty different: in structural biology, all you care about is isolating a single large and very pure crystal, while uniformity and reproducibility are paramount in preparative crystallography.

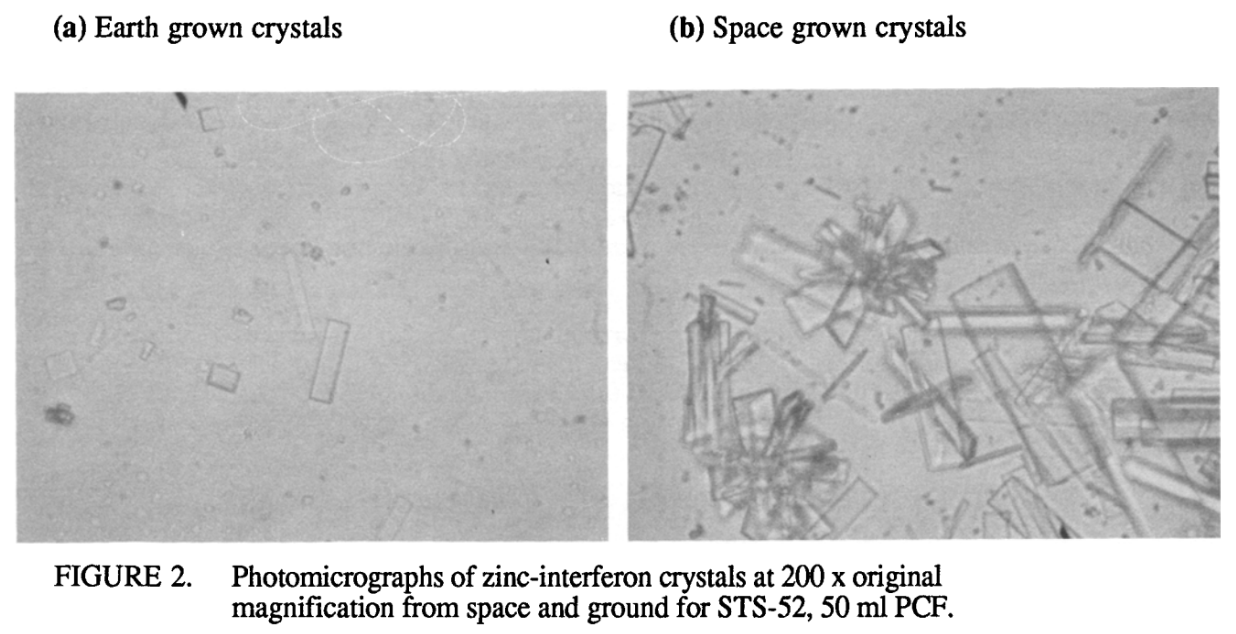

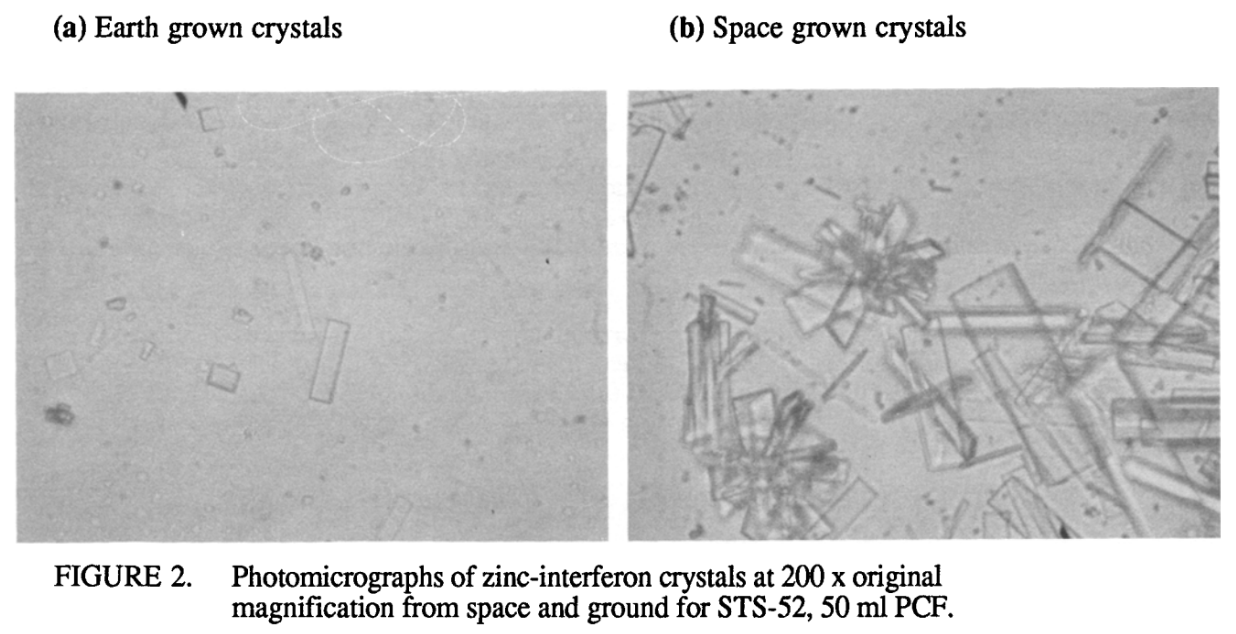

There’s some precedent for preparative protein crystallization in microgravity: a 1996 Schering-Plough paper studied crystallization of zinc interferon-α2b on the Space Shuttle. The results are excellent: over 95% of the protein crystallized, and the resulting suspension showed good stability and improved serum half-life in Cynomolgus monkeys (ref, ref). The difference in crystal quality is huge:

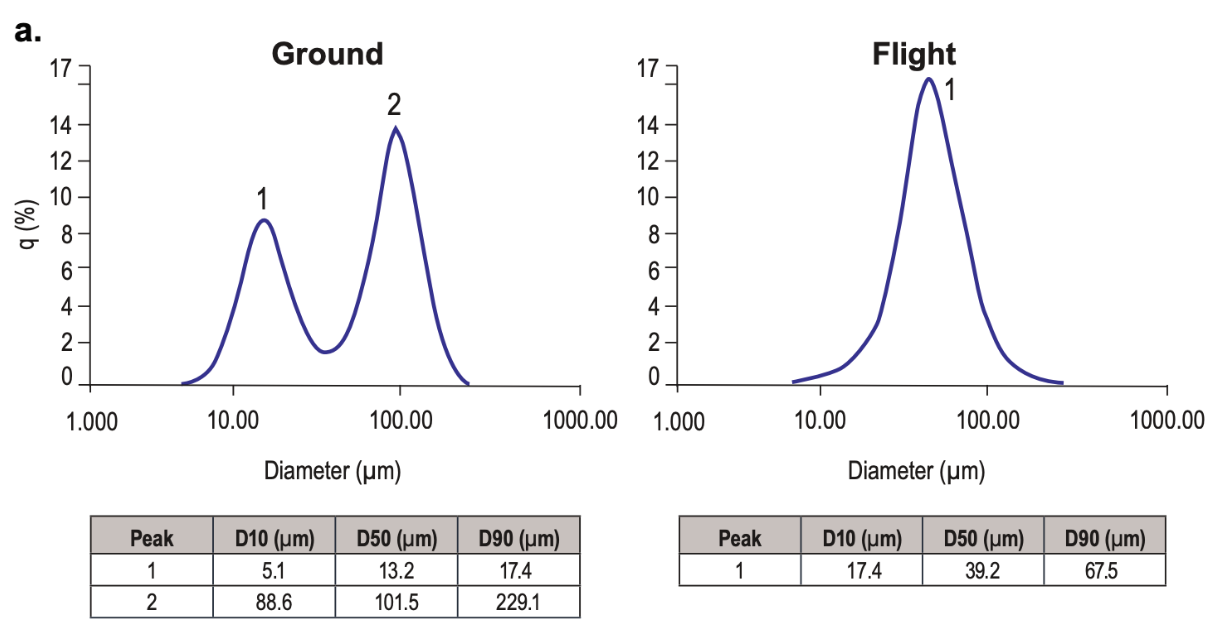

More recently, scientists from Merck found that crystallization of pembrolizumab (Keytruda) in microgravity reproducibly formed a monomodal particle size distribution, as opposed to the bimodal particle size distribution formed under conventional conditions (ref), although the crystals didn’t seem any larger:

Of course, until recently access to space was very limited and there wasn’t much reason to study preparative protein crystallography in microgravity, so the lack of studies is hardly surprising. For all the reasons discussed above, it seems very likely that preparative crystallography will be generally better in microgravity, and that the resulting crystals will be more homogenous and more pure than the crystals you could grow on Earth. But it’s not 100% certain, and that’s something Varda will have to establish. The word “can” is doing a lot of work in this text from their website:

By eliminating factors such as natural convection and sedimentation, processing in a microgravity environment provides a unique path to formulating small molecules and biologics that traditional manufacturing processes cannot address. The resulting tunable particle size distributions, more ordered crystals, and new forms can lead to improved bioavailability, extended shelf-life, new intellectual property, and new routes of administration (emphasis added)

Another concern is that little work (that I’m aware of) has been done on small molecule crystallization in microgravity—the very task Varda intends to start with. Small molecules, in general, are much easier to crystallize than proteins, and there are more parameters for the experimental scientist to tune. While there are certainly cases where small molecule crystals can display unexpected or problematic behaviors (like the famous case of ritonavir, the molecule Varda is investigating first), in general crystallization of small molecules seems like an easier problem, and one for which there are better state-of-the-art workarounds.

The most likely failure mode to me, though, is just that microgravity crystallization is better than crystallization on Earth, but not that much better. Shooting APIs into space, waiting for them to crystallize, and then launching them back to Earth is going to be really expensive, and Varda will have to demonstrate extraordinary results to justify the added hassle—particularly for a technique that they hope to make a key part of the pharmaceutical manufacturing process. Talk about supply chain risk! (Is this all going to be GMP?)

And it’s worth pointing out a fairly obvious consideration too: what Varda is proposing to do in space is only one part of a vast, multi-step operation. No synthesis will take place in space, so all the manufacturing of either proteins or small molecules will take place on Earth. The purified products will then be launched into space, crystallized, and then the crystal-containing solution will undergo reentry and then be formulated into whatever final form the drug needs to be administered in.

So, although “there are a number of small molecules that fetch hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars per kg” (Not Boring), Varda can address only a small—albeit important—part of the manufacturing process. I doubt this is likely to change. On average, it takes 100–1000 kg of raw materials to manufacture 1 kg of a small molecule drug (ref), so shipping everything to orbit would massively raise costs, without any obvious advantages that I can think of. The TAM for Varda might be large enough to break even, but it’s not going to replace conventional pharmaceutical manufacturing anytime soon.

Varda’s pitch is perfect for venture capital: ambitious, risky, and potentially game-changing if it succeeds. And I wish them luck in their quest, since new and better ways to approach formulation would be awesome. But I can’t shake the nagging doubt that they’re so excited about the image of space-based manufacturing that they’re trying to invent a problem that their aerospace engineers have a solution for. We’ll find out soon enough if they’ve succeeded.