Much ink has been spilled on whether scientific progress is slowing down or not (e.g.). I don’t want to wade into that debate today—instead, I want to argue that, regardless of the rate of new discoveries, acquiring scientific data is easier now than it ever has been.

There are a lot of ways one could try to defend this point; I’ve chosen some representative anecdotes from my own field (organic chemistry), but I’m sure scientists in other fields could find examples closer to home.

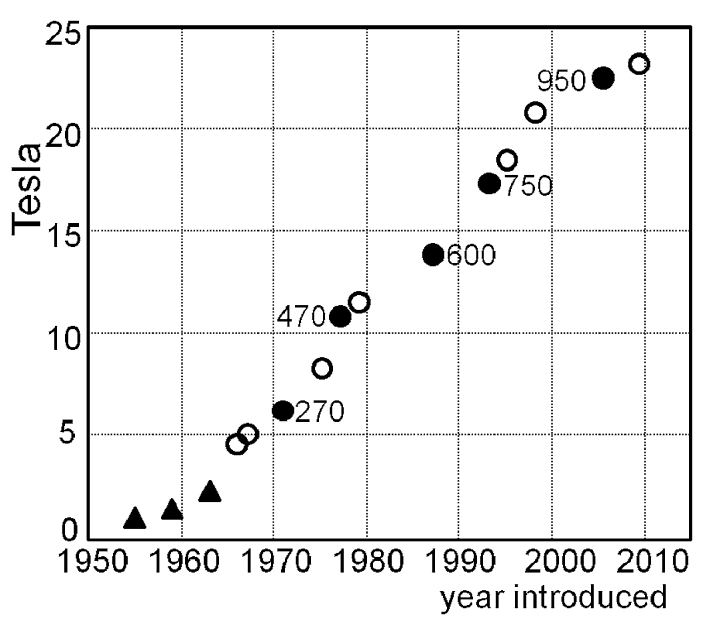

NMR spectroscopy is now the primary method for characterization and structural study of organic molecules, but it wasn’t always very good. The last half-century has seen a steady increase in the quality of NMR spectrometers (principally driven by the development of more powerful magnetic fields), meaning that even a relatively lackluster NMR facility today has equipment beyond the wildest dreams of a scientist in the 1980s:

The number of compounds available for purchase has markedly increased in recent years. In the 1950s, the Aldrich Chemical Company’s listings could fit on a single page, and even by the 1970s Sigma-Aldrich only sold 40,000 or so chemicals (source).

But things have changed. Nowadays new reagents are available for purchase within weeks or months of being reported (e.g.), and companies like Enamine spend all their time devising new and quirky structures for medicinal chemists to buy.

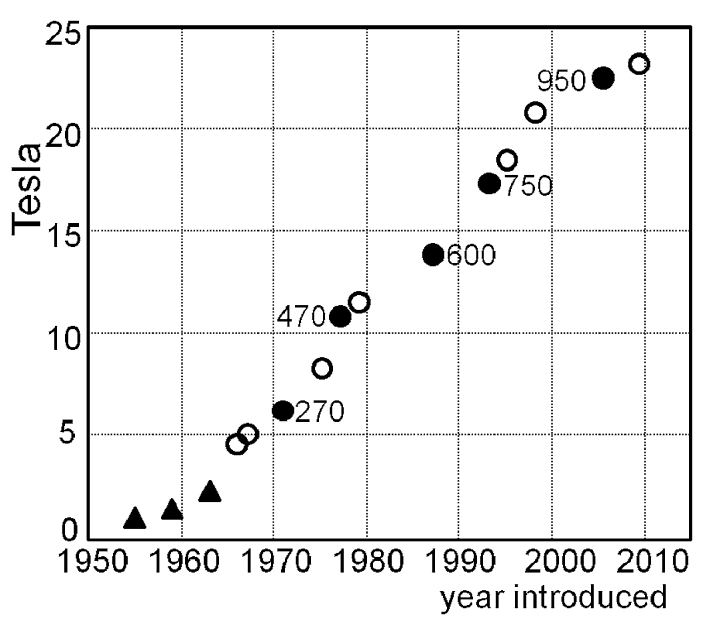

One way to quantify how many compounds are for sale today is through the ZINC database, aimed at collecting compounds for virtual screening, which is updated every few years or so. The first iteration of ZINC, in 2005, had fewer than a million compounds: now there are almost 40 billion:

(Most compounds in the ZINC database aren’t available on synthesis scale, so it’s not like you can order a gram of all 40 billion compounds—there’s probably more like 3 million “building blocks” today, which is still a lot more than 40,000.)

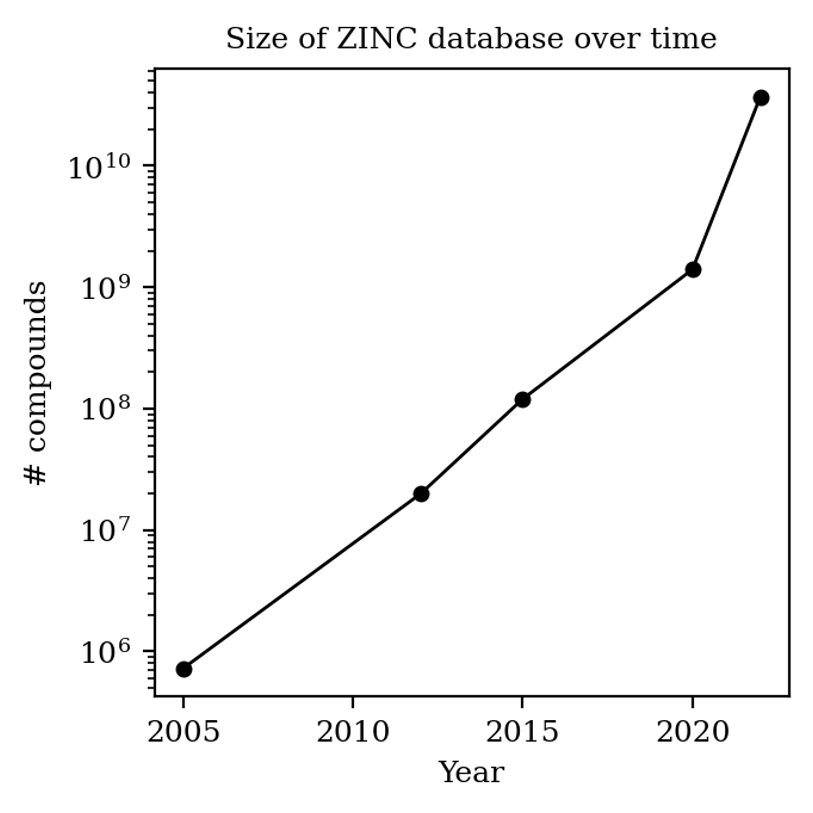

Chromatography, the workhorse of synthetic and analytical chemistry, has also gotten a lot better. Separations that took almost an hour can now be performed in well under a minute, accelerating purification and analysis of any new material (this paper focuses on chiral stationary phase chromatography, but many of the advances translate to other forms of chromatography too).

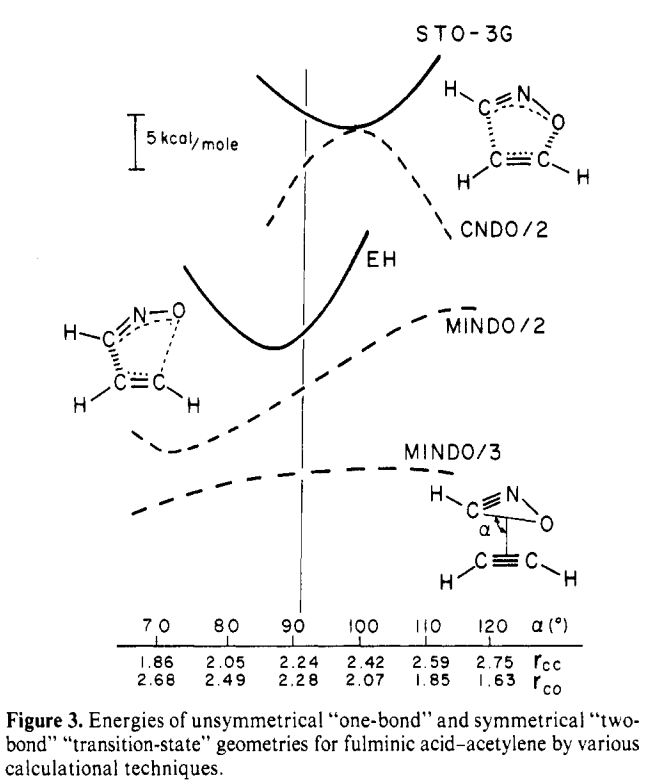

Moore’s Law is powerful. In the 1970s, using semiempirical methods and minimal basis set Hartree–Fock to investigate an 8-atom system was cutting-edge, as demonstrated by this paper from Ken Houk:

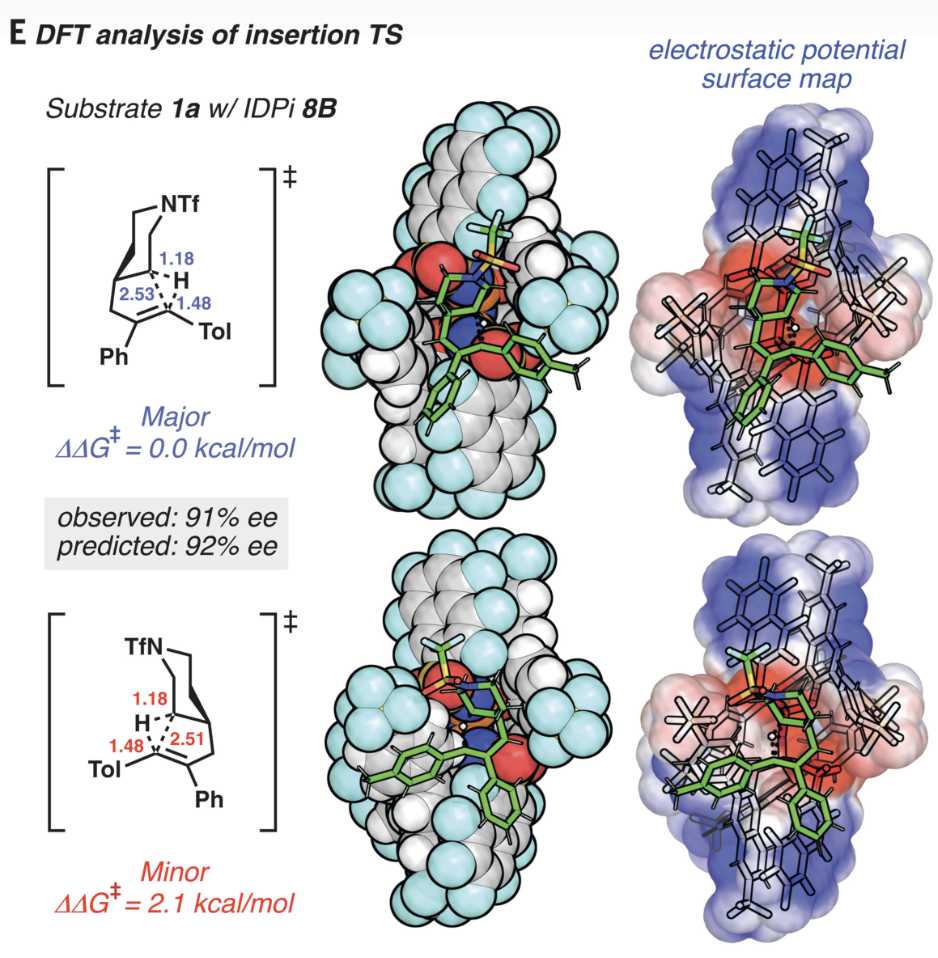

Now, that calculation would probably take only a few seconds on my laptop computer, and it’s becoming increasingly routine to perform full density-functional theory or post-Hartree–Fock studies on 200+ atom systems. A recent paper, also from Ken Houk, illustrates this nicely:

The fact that it’s now routine to perform conformational searches and high-accuracy quantum chemical calculations on catalyst•substrate complexes with this degree of flexibility would astonish anyone from the past. (To be fair to computational chemists, it’s not all Moore’s Law—advances in QM tooling also play a big role.)

There are lots of advances that I haven’t even covered, like the general improvement in synthetic methodology and the rise of robotics. Nevertheless, I think the trend is clear: it’s easier to acquire data than it’s ever been.

What, then, do we do with all this data? Most of the time, the answer seems to be “not much.” A recent editorial by Marisa Kozlowski observes that the average number of substrates in Organic Letters has increased from 17 in 2009 to 40 in 2021, even as the information contained in these papers has largely remained constant. Filling a substrate scope with almost identical compounds is a boring way to use more data; we can do better.

The availability of cheap data means that scientists can—and must—start thinking about new ways to approach experimental design. Lots of academic scientists still labor under the delusion that “hypothesis-driven science” is somehow superior to HTE, when in fact the two are ideal complements to one another. “Thinking in 96-well plates” is already common in industry, and should become more common in academia; why run a single reaction when you can run a whole screen?

New tools are needed to design panels, run reactions, and analyze the resultant data. One nice entry into this space is Tim Cernak’s phactor, a software package for high-throughput experimentation, and I’m sure lots more tools will spring up in the years to come. (I’m also optimistic that multi-substrate screening, which we and others have used in “screening for generality,” will become more widely adopted as HTE becomes more commonplace.)

The real worry, though, is that we will refuse to change our paradigms and just use all these improvements to publish old-style papers faster. All the technological breakthroughs in the world won’t do anything to accelerate scientific progress if we refuse to open our eyes to the possibilities they create. If present trends continue, it may be possible in 5–10 years to screen for a hit one week, optimize reaction conditions the next week, and run the substrate scope on the third week. Do we really want a world in which every methodology graduate student is expected to produce 10–12 low-quality papers per year?