I’m writing my dissertation right now, and as a result I’m going back through a lot of old slides and references to fill in details that I left out for publication.

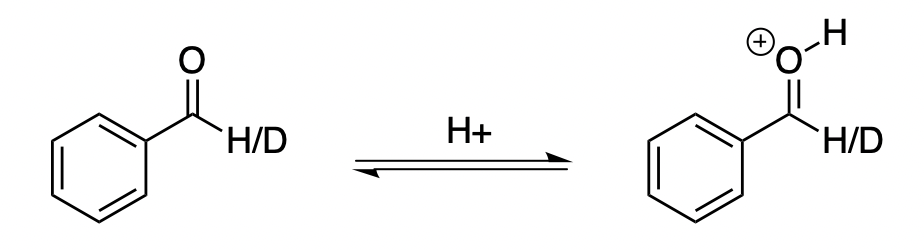

One interesting question that I’m revisiting is the following: when protonating benzaldehyde, what is the H/D equilibrium isotope effect at the aldehyde proton? This question was relevant for the H/D KIE experiments we conducted in our study of the asymmetric Prins cyclization. (The paper hasn’t gotten much attention, but it’s probably the most “classic” organic chemistry paper I’ve worked on, with a minimum of weird computational details or bizarre analytical techniques.)

Since the H/D bond isn’t involved in the reaction, we won’t see a primary effect; so we know we have to be thinking in terms of secondary effects. The most common reason to observe a secondary isotope effect is changes in hybridization: sp3 to sp2 gives a normal effect, whereas sp2 to sp3 gives an inverse effect. From this perspective, it looks like the effect should be unity, since the carbon in question is sp2 in both structures.

Reality, however, disagrees. Hall and Milosevich report a EIE of 0.94 for benzaldehyde in aq. sulfuric acid, and Gajewski and co-authors compute an EIE of 0.83 for acetaldehyde at the MP2/6-31G(d,p) level of theory. I performed my own calculations at the M06-2X/jun-cc-pVTZ level of theory and obtained an EIE of 0.851 with PyQuiver, qualitatively consistent with the above results.

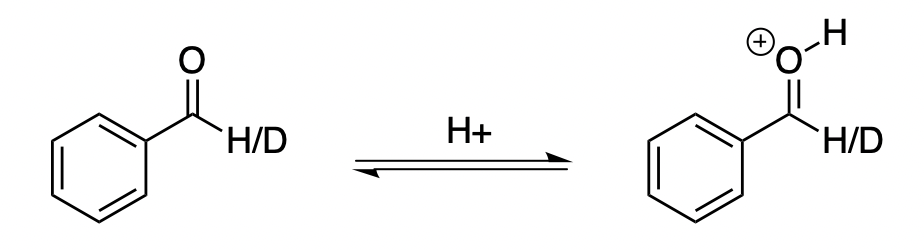

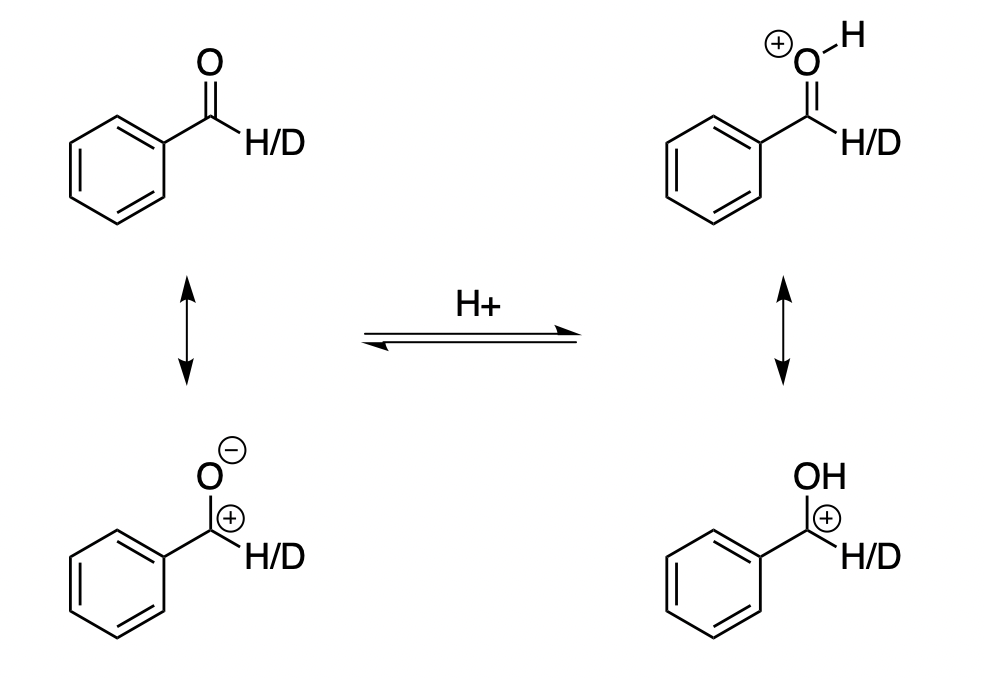

Where does this EIE come from? It’s helpful to think of benzaldehyde as possessing multiple resonance forms:

We typically think of the neutral resonance form on the top left, but you can also imagine putting a positive charge on carbon and a negative charge on oxygen to create a zwitterion with a C–O single bond (bottom left). In neutral benzaldehyde, this resonance form is substantially disfavored, but in protonated benzaldehyde it doesn’t look any worse than the “normal” top resonance form!

If this is true, we’d expect the C–O bond order to decrease from 2 in neutral benzaldehyde to ~1.5 in protonated benzaldehyde. Indeed, in my calculations the bond length increases from 1.20 Å to 1.28 Å upon protonation—so it seems the double bond character is decreasing! It’s not quite the same as going from sp2 to sp3, but the inverse KIE begins to make sense.

(This is purely guesswork, but my guess would be that the differences between the two structures are attenuated in a polar solvent like water. The zwitterionic resonance form of the neutral structure will be stabilized and thus the neutral aldehyde will be more polar, making the change to the oxocarbenium less drastic. This might explain why the measured EIE in water is smaller—although this might also be due to counterion effects, or something completely unrelated.)

Let’s go a level deeper. According to Streitwieser, secondary KIEs associated with hyperconjugation originate from the creation or destruction of the c. 800 cm-1 out-of-plane bending vibrations of Csp2–H hydrogens, which are markedly lower in frequency than the c. 1350 cm-1 bending vibrations associated with Csp3–H hydrogens.

Raising the frequency of a mode increases the energy required to inhabit the ground vibrational state (the “zero-point energy”)—but deuterium is heavier and vibrates more slowly, meaning that it possesses less ZPE and is less affected by these changes. So when an 800 cm-1 sp2 mode transforms to a 1350 cm-1 sp3 mode, the ZPE increases, but less for D than for H, so D is favored. Conversely, when a 1350 cm-1 sp3 mode transforms to a 800 cm-1 sp2 mode, the ZPE decreases, but less for D than for H, so H is favored. (For a more complete explanation, see this presentation by Rob Knowles.)

This effect is complicated for benzaldehyde by the fact that the out-of-plane bend of the aldehyde couples to the out-of-plane bend of the phenyl ring, so there are several modes involving out-of-plane vibration of the aldehyde proton. When I compared the out-of-plane bend of the aldehyde H in both structures, I saw only minimal differences: 771, 963, 1040, and 1051 cm-1 for the neutral species, as compared to 790, 1003, and 1061 cm-1 for the protonated species. These small differences can’t be responsible for the observed effect.

In contrast, the in-plane C–H bend shows a big change—1430 cm-1 for benzaldehyde, but 1644 cm-1 for the oxocarbenium (it seems to couple to the C–O stretch; the reduced mass increases from 1.26 amu to 3.52 amu). Applying Streitweiser’s formula for estimating the isotope effect for a specific mode gives a pretty good match:

kH/kD ≈ exp(0.187/T * ∆ν) = exp(0.187/298 * (-214)) = 0.87

I don’t understand this area well enough to comment on why there’s a change in the in-plane vibrational frequency and not the out-of-plane vibrational frequency, nor do I understand how to deconvolute the effects of mode-to-mode coupling. Nevertheless, this provides a tentative physical rationale for the observation.

On a more abstract level, this case study illustrates why isotope effects are such a good tool. Any transformation that perturbs the vibrational frequencies of a given molecule can, in principle, be monitored by isotope effects without affecting the electronic energy surface at all. So, although the precise nature and magnitude of the effect might be hard to predict a priori, it’s not surprising that a transformation as dramatic as protonating a functional group produces a sizable isotope effect.