It’s a truth well-established that interdisciplinary research is good, and we all should be doing more of it (e.g. this NSF page). I’ve always found this to be a bit uninspiring, though. “Interdisciplinary research” brings to mind a fashion collaboration, where the project is going to end up being some strange chimera, with goals and methods taken at random from two unrelated fields.

Rather, I prefer the idea of “domain arbitrage.”1 Arbitrage, in economics, is taking advantage of price differences in different markets: if bread costs $7 in Cambridge but $4 in Boston, I can buy in Boston, sell in Cambridge, and pocket the difference. Since this is easy and requires very little from the arbitrageur, physical markets typically lack opportunities for substantial arbitrage. In this case, the efficient market hypothesis works well.

Knowledge markets, however, are much less efficient than physical markets—many skills which are cheap in a certain domain are expensive in other domains. For instance, fields that employ organic synthesis, like chemical biology or polymer chemistry, have much less synthetic expertise than actual organic synthesis groups. The knowledge of how to use a Schlenk line properly is cheap within organic chemistry but expensive everywhere else. And organic chemists certainly don’t have a monopoly on scarce skills: trained computer scientists are very scarce in most scientific fields, as are statisticians, despite the growing importance of software and statistics to almost every area of research.

Domain arbitrage, then, is taking knowledge that’s cheap in one domain to a domain where it’s expensive, and profiting from the difference. I like this term better because it doesn’t imply that the goal of the research has to be interdisciplinary—instead, you’re solving problems that people have always wanted to solve, just now with innovative methods. And the concept of arbitrage highlights how this can be beneficial for the practitioner. You’re bringing new insights to your field so you can help your own research and make cool discoveries, not because you’ve been told that interdisciplinary work is good in an abstract way.

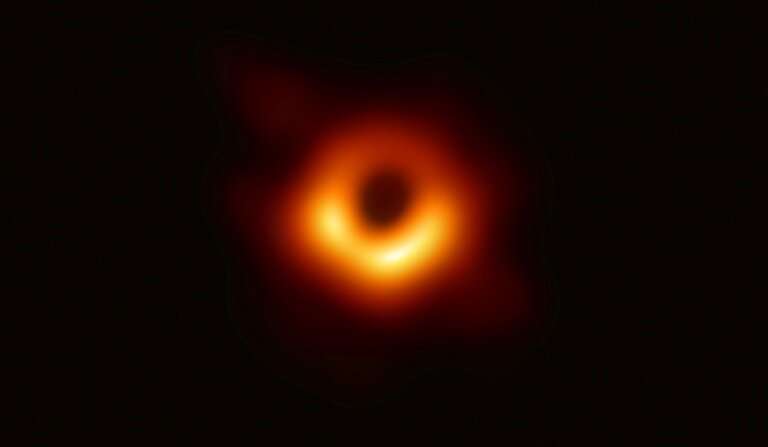

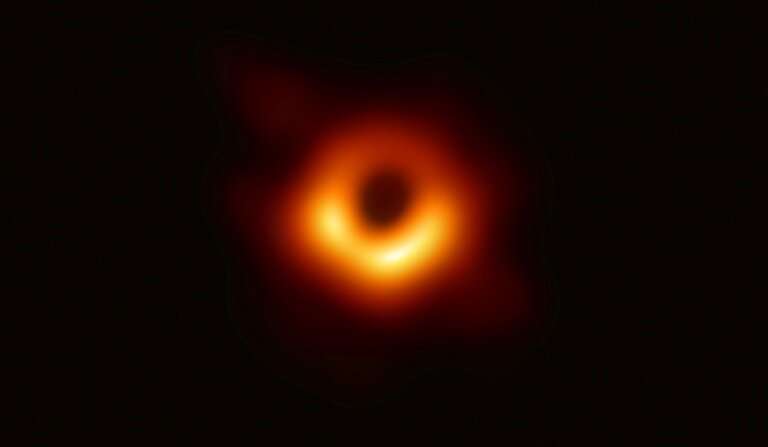

There are many examples of domain arbitrage,2 but perhaps my favorite is the recent black hole image, which was largely due to work by Katie Bouman (formerly a graduate student at MIT, now a professor at Caltech):

What’s surprising is that Bouman didn’t have a background in astronomy at all: she “hardly knew what a black hole was” (in her words) when she started working on the project. Instead, Bouman’s work drew on her background in computer vision, adapting statistical image models to the task of reconstructing astronomical images. In a 2016 paper, she explicitly credits computer vision with the insights that would later lead to the black hole image, and concludes by stating that “astronomical imaging will benefit from the crossfertilization of ideas with the computer vision community.”

If we accept that domain arbitrage is important, why doesn’t it happen more often? I can think of a few reasons: some fundamental, some structural, and some cultural. On the fundamental level, domain arbitrage requires knowledge of two fields of research at a more-than-superficial level. This is relatively common for adjacent fields of research (like organic chemistry and inorganic chemistry), but becomes increasingly rare as the distance between the two fields grows. It’s not enough to just try and read journals from other fields occasionally—without the proper context, other fields are simply unintelligible. Given how hard achieving competence in a single area of study can be, we should not be surprised that those with a working knowledge of multiple fields are so scarce.

The structure of our research institutions also makes domain arbitrage harder. In theory, a 15-person research group could house scientists from a variety of backgrounds: chemists, biologists, mathematicians, engineers, and so forth, all focused on a common research goal. In practice, the high rate of turnover in academic positions makes this challenging. Graduate students are only around for 5–6 years, postdocs for fewer, and both positions are typically filled by people hoping to learn things, not by already competent researchers. Thus, senior lab members must constantly train newer members in various techniques, skills, and ways of thinking so that institutional knowledge can be preserved.

This is hard but doable for a single area of research, but quickly becomes untenable as the number of fields increases. A lab working in two fields has to pass down twice as much knowledge, with the same rate of personnel turnover. In practice, this often means that students end up deficient in one (or both) fields. As Derek Lowe put it when discussing chemical biology in 2007:

I find a lot of [chemical biology] very interesting (though not invariably), and some of it looks like it could lead to useful and important things. My worry, though, is: what happens to the grad students who do this stuff? They run the risk of spending too much time on biology to be completely competent chemists, and vice versa.

To me, this seems like a case in which the two goals of the research university—to teach students and to produce research—are at odds. It’s easier to teach students in single-domain labs, but the research that comes from multiple domains is superior. It’s not easy to think about how to address this without fundamental change to the structure of universities (although perhaps others have more creative proposals than I).3

But, perhaps most frustratingly, cultural factors also contribute to the rarity of domain arbitrage. Many scientific disciplines today define themselves not by the questions they’re trying to solve but by the methods they employ, which disincentivizes developing innovative methods. For example, many organic chemists feel that biocatalysis shouldn’t be considered organic synthesis, since it employs enzymes and cofactors instead of more traditional catalysts and reagents, even though organic synthesis and biocatalysis both address the same goal: making molecules. While it’s somewhat inevitable that years of lab work leaves one with a certain affection for the methods one employs, it’s also irrational.

Now, one might reasonably argue that precisely delimiting where one scientific field begins and another ends is a pointless exercise. Who’s to say whether biocatalysis is better viewed as the domain of organic chemistry or biochemistry? While this is fair, it’s also true that the scientific field one formally belongs to matters a great deal. If society deems me an organic chemist, then overwhelmingly it is other organic chemists who will decide if I get a PhD, if I obtain tenure as a professor, and if my proposals are funded.4

Given that the success or failure of my scientific career thus depends on the opinion of other organic chemists, it starts to become apparent why domain arbitrage is difficult. If I attempt to solve problems in organic chemistry by introducing techniques from another field, it’s likely that my peers will be confused or skeptical by my work, and hesitate to accept it as “real” organic chemistry (see, for instance, the biocatalysis scenario above). Conversely, if I attempt to solve problems in other domains with the tools of organic chemistry, my peers will likely be uninterested in the outcome of the research, even if they approve of the methods employed. So from either angle domain arbitrage is disfavored.

The factors discussed here don’t serve to completely halt domain arbitrage, as successful arbitrageurs like Katie Bouman or Frances Arnold demonstrate, but they do act to inhibit it. If we accept the claim that domain arbitrage is good, and we should be working to make it more common, what then should we do to address these problems? One could envision a number of structural solutions, which I won’t get into here, but on a personal level the conclusion is obvious: if you care about performing cutting-edge research, it’s important to learn things outside the narrow area that you specialize in and not silo yourself within a single discipline.

Thanks to Shlomo Klapper and Darren Zhu for helpful discussions. Thanks also to Ari Wagen, Eric Gilliam, and Joe Gair for editing drafts of this post; in particular, Eric Gilliam pointed out the cultural factors discussed in the conclusion of the post.