When thinking about science, I find it helpful to divide computations into two categories: models and oracles.

In this dichotomy, models are calculations which act like classic ball-and-stick molecular models. They illustrate that something is geometrically possible—that the atoms can literally be arranged in the proper orientation—but not much more. No alternative hypotheses have been ruled out, and no unexpected insights have emerged. A model has no intelligence of its own, and only reflects the thought that the user puts into it.

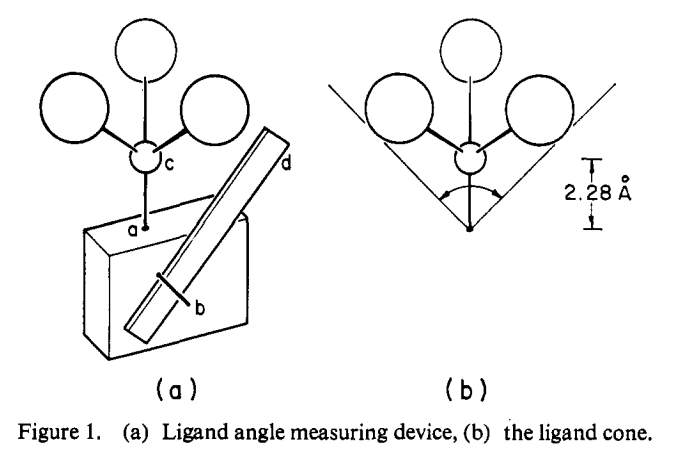

This isn’t bad! Perhaps the most striking example of the utility of models is Tolman’s original cone angle report, where he literally made a wooden model of different phosphine ligands and measured the cone angle with a ruler. The results are excellent!

In contrast, an oracle bestows new insights or ideas upon a petitioner—think the Oracle at Delphi. This is what a lot of people imagine when they think of computation: we want the computer to predict totally unprecedented catalysts, or figure out the mechanism without any human input. We bring our problems to the superintelligence, and it solves them for us.

In reality, every simulation is somewhere between these two limiting extremes. No matter how hard you try, a properly executed DFT calculation will not predict formation of a methyl cation to be a low-barrier process—the computational method used understands enough chemistry to rule this out, even if the user does not. On the flip side, even the most sophisticated calculations all involve some form of human insight or intuition, either explicitly or implicitly. We’re still very far away from the point where we can ask the computer to generate the structures of new catalysts (or medicines) and expect reasonable, trustworthy results. But that’s ok; there’s a lot to be gained from lesser calculations! There’s no shame in generating computational models instead of oracles.

What’s crucial, though, is to make sure that everyone—practitioners, experimentalists, and readers—understands where a given calculation falls on the model–oracle continuum. An expert might understand that a semiempirical AIMD study of reaction dynamics is likely to be only qualitatively correct (if that), but does the casual reader? I’ve talked to an unfortunate number of experimental chemists who think a single DFT picture means that we can “predict better catalysts,” as if that were a button in GaussView. The appeal of oracles is seductive, and we have to be clear when we’re presenting models instead. (This ties into my piece about computational nihilism.)

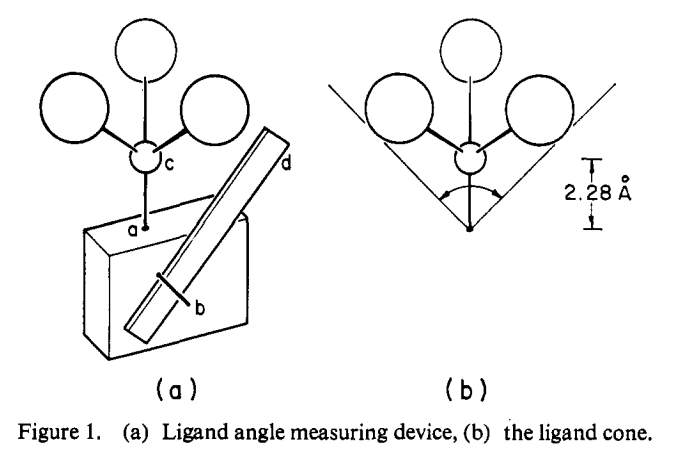

Finally, this piece would be incomplete if I didn’t highlight Jan Jensen and co-workers’ recent work on automated design of catalysts for the Morita–Baylis–Hillman reaction. The authors use a generative model to discover tertiary amines with lower DFT-computed barriers than DABCO (the usual catalyst), and then experimentally validate one of their candidates, finding that it is indeed almost an order-of-magnitude faster than DABCO. It’s difficult to underscore how groundbreaking this result is; as the authors dryly note, “We believe this is the first experimentally verified de novo discovery of an efficient catalyst using a generative model.” On the spectrum discussed above, this is getting pretty close to “oracle.”

Nevertheless, the choice of model system illustrates how far the field still has to go. The MBH reaction is among the best-studied reactions in organic chemistry, as illustrated by Singleton’s 2015 mechanistic tour de force (and references therein, and subsequent work), so Jensen and co-workers could have good confidence that the transition state they were studying was correct and relevant. Furthermore, as I understand it, the MBH reaction can be catalyzed by just about any tertiary amine—there aren’t the sort of harsh activity cliffs or arcane structural requirements that characterize many other catalytic reactions. Without either of these factors—well-studied mechanism or friendly catalyst SAR—I doubt this work would be possible.

This point might seem discouraging, but I mean it in quite the opposite way. De novo catalyst design isn’t impossible for mysterious and opaque reasons, but for quite intelligible reasons—mechanisms are complicated, catalysts are hard to design, and we just don’t understand enough about what we’re doing, experimentally or computationally. What Jensen has shown us is that, if we can address these issues, we can expect to start converging on oracular results. I find this very exciting!

Jan Jensen was kind enough to reply to this post on Twitter with a few thoughts and clarifications, which are worth reading.

If you want email updates when I write new posts, you can subscribe on Substack.