The failure of conventional calculations to handle entropy is well-documented. Entropy, which fundamentally depends on the number of microstates accesible to a system, is challenging to describe in terms of a single set of XYZ coordinates (i.e. a single microstate), and naïve approaches to computation simply disregard this important consideration.

Most programs get around this problem by partitioning entropy into various components—translational, rotational, vibrational, and configurational—and handling each of these separately. For many systems, conventional approximations perform well. Translational and rotational entropy depend in predictable ways on the mass and moment of inertia of the molecule, and vibrational entropy can be estimated from normal-mode analysis at stationary points. Conformational entropy is less easily automated and as a result is often neglected in the literature (see the discussion in the SI), although some recent publications are changing that.

In general, however, the approximations above only work for ground states. To quote the Gaussian vibrational analysis white paper:

Vibrational analysis, as it’s descibed in most texts and implemented in Gaussian, is valid only when the first derivatives of the energy with respect to displacement of the atoms are zero. In other words, the geometry used for vibrational analysis must be optimized at the same level of theory and with the same basis set that the second derivatives were generated with. Analysis at transition states and higher order saddle points is also valid. Other geometries are not valid.

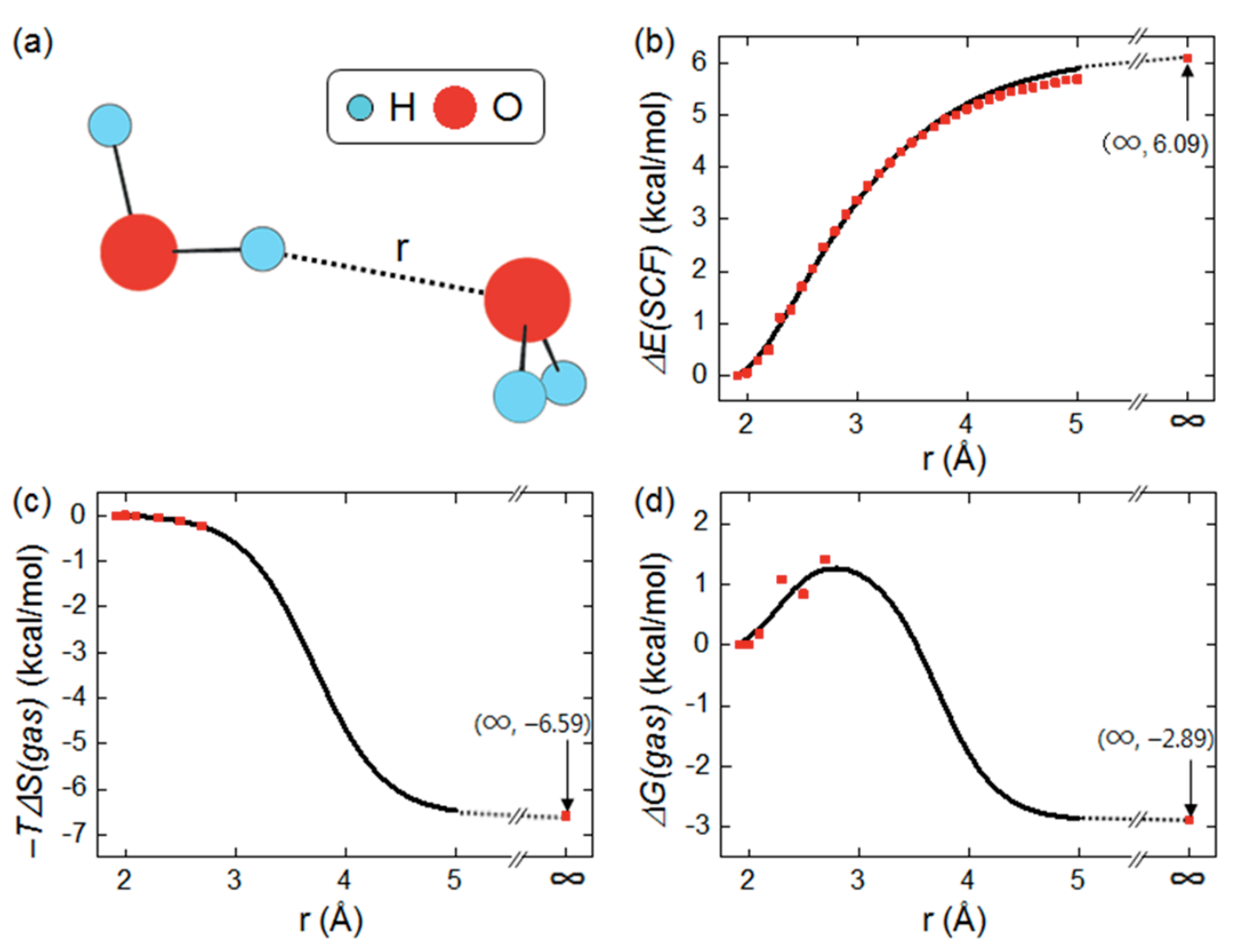

While this isn't a huge issue in most cases, since most processes are associated with a minima or first-order saddle point on the electronic energy surface, it can become a big deal for reactions where entropy significantly shifts the position of the transition state (e.g. Figure 4 in this study of cycloadditions). Even worse, however, are cases where entropy constitutes the entire driving force for the reaction: association/dissociation processes. In his elegant review of various failures of computational modelling, Mookie Baik illustrated this point by showing that no transition state could be found for dissociation of the water dimer in the gas phase:

Panel (b) of this figure shows the electronic energy surface for dissociation, which monotonically increases out to infinity—there's never a maximum, and so there's no transition state. To estimate the position of the transition state, Baik proposes computing the entropy (using the above stationary-point approximations) at the first few points, where the two molecules are still tightly bound, and then extrapolating the curve into a sigmoid function. Combining the two surfaces then yields a nice-looking (if noisy) curve with a clear transition state at an O–H distance of around 3 Å.

This approach, while clever, seems theoretically a bit dubious—is it guaranteed that entropy must always follow a smooth sigmoidal interpolation between bound and unbound forms? I thought that a more direct solution to the entropy problem would take advantage of ab initio molecular dynamics. While too slow for most systems, AIMD intrinsically accounts for entropy and thus should be able to generate considerably more accurate energy surfaces for association/dissociation events.

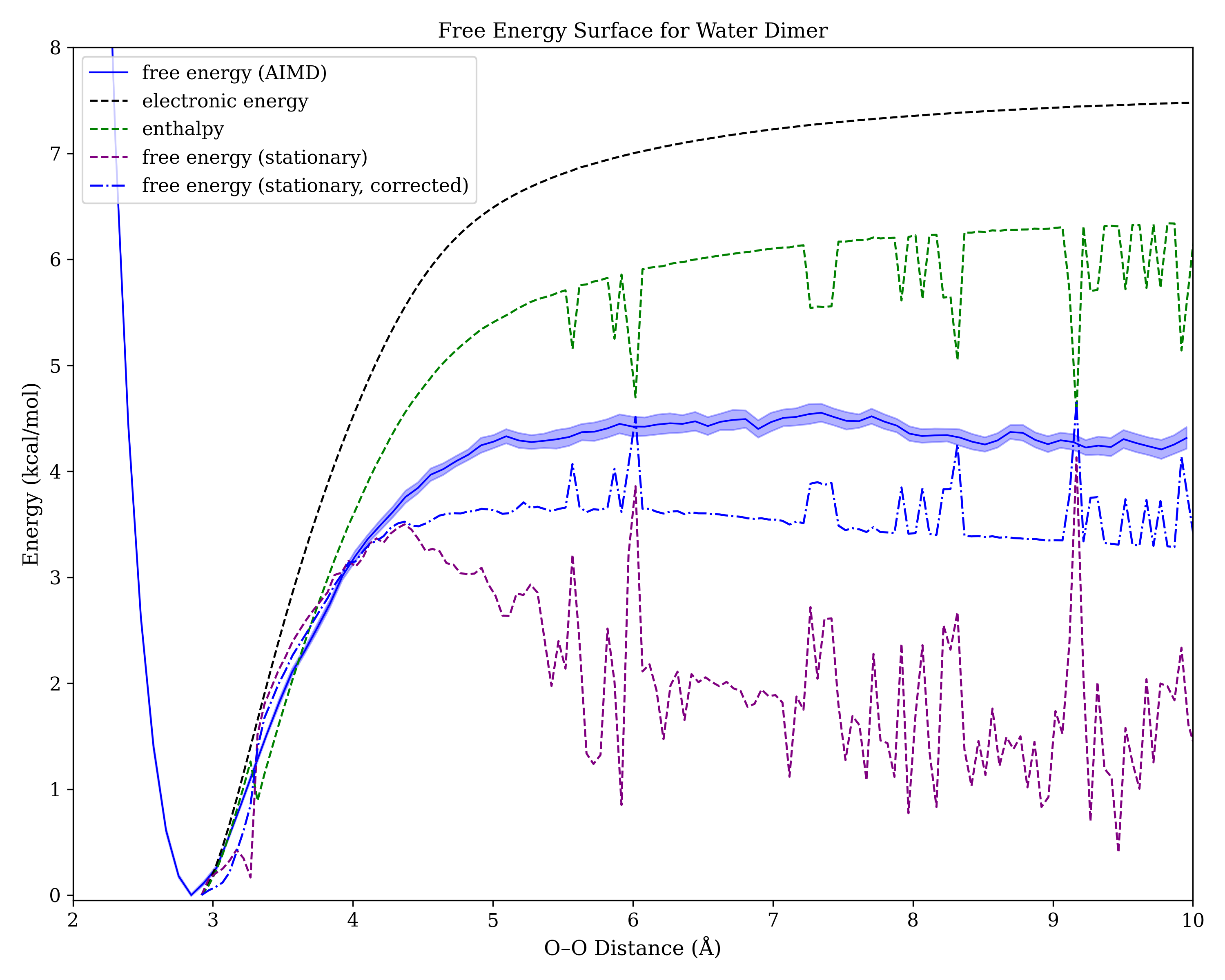

Using presto, I ran 36 constrained 100 ps NVT simulations of the water dimer with different O–O distances, and used the weighted histogram analysis method to stitch them together into a final potential energy surface. I then compared these results to those obtained from a direct opt=modredundant calculation (with frequencies at every point) from Gaussian. (All calculations were performed in Gaussian 16 at the wB97XD/6-31G(d) level of theory, which overbinds the water dimer a bit owing to basis-set superposition error.)

The results are shown below (error bars from the AIMD simulation are derived from bootstrapping):

As expected, no transition state can be seen on the black line corresponding to the electronic energy surface, or on the green line corresponding to enthalpy. All methods that depend on normal-mode analysis show sizeable variation at non-stationary points, which is perhaps unsurprising. What was more surprising was how much conventional DFT calculations (purple) overestimated entropy relative to AIMD! Correcting for low-frequency vibrational modes brought the DFT values more into line with AIMD, but a sizeable discrepancy persists.

Also surprising is how different the AIMD free energy surface looks from Baik's estimated free energy surface. Although the scales are clearly different (I used O–O distance for the X axis, whereas Baik used O–H distance), the absence of a sharp maximum in both the AIMD data and the corrected Gibbs free energy data from conventional DFT is striking. Is this another instance of entropy–enthalpy compensation?

In the absence of good gas-phase estimates of the free energy surface, it's tough to know how far the AIMD curve is from the true values; perhaps others more skilled in these issues can propose higher-level approaches or suggest additional sources of error. Still, on the meta-level, this case study demonstrates how molecular dynamics holds promise for modelling things that just can't be modelled other ways. Although this approach is still too expensive for medium to large systems, it's exciting to imagine what might be possible in 5 or 10 years!

Thanks to Richard Liu and Eugene Kwan for insightful discussions about these issues.