Multi-substrate screening is proposed as one of many different algorithms.

Now that our work on screening for generality has finally been published in Nature, I wanted to first share a few personal reflections and then highlight the big conclusions that I gleaned from this project.

This project originated from conversations I had with Eugene Kwan back in February 2019, when I was still an undergraduate at MIT. Although at the time our skills were almost completely non-overlapping, we shared both an interest in “big data” and high-throughput experimentation and a conviction that organic chemistry could benefit from more careful thinking about optimization methods.

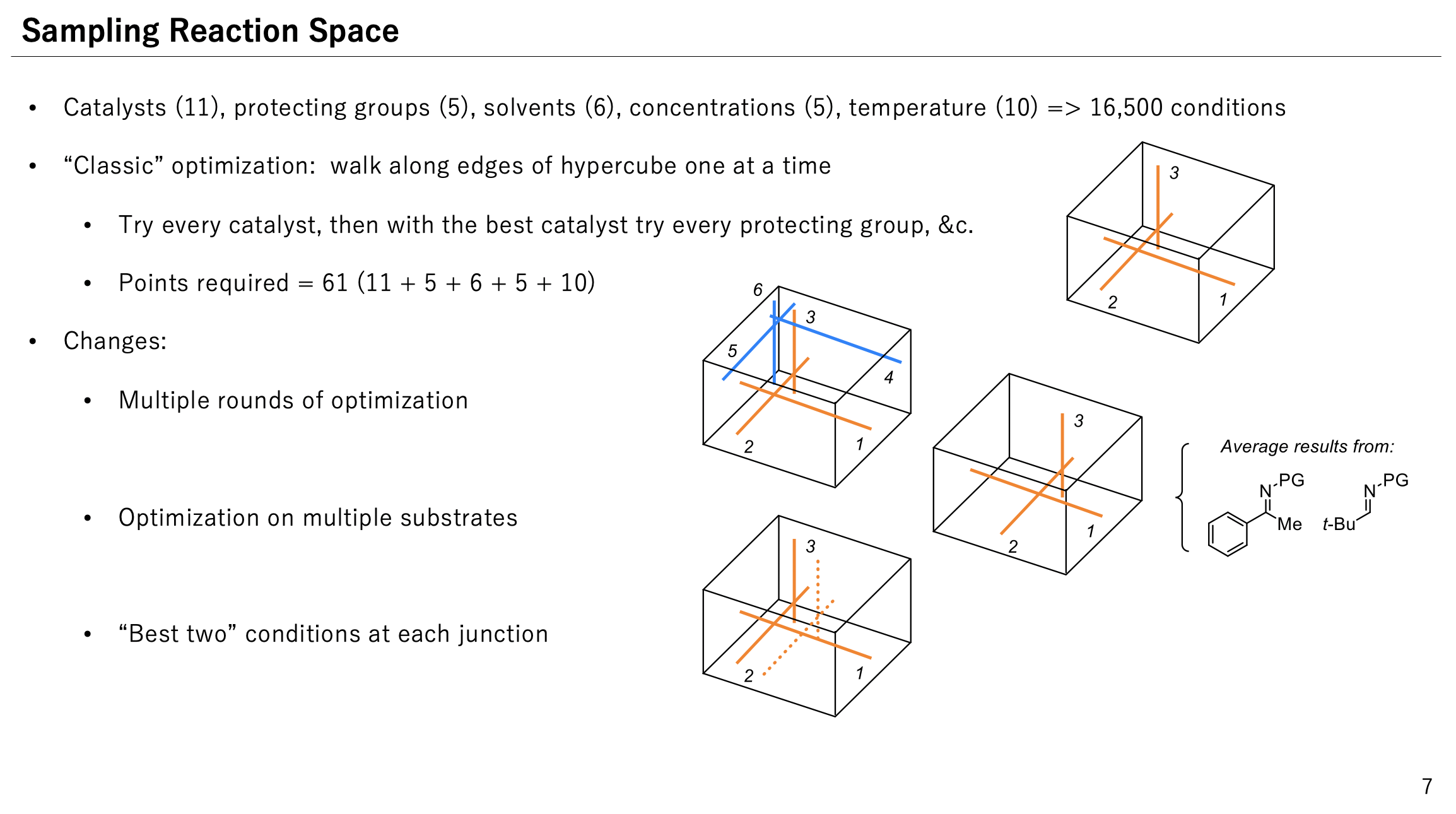

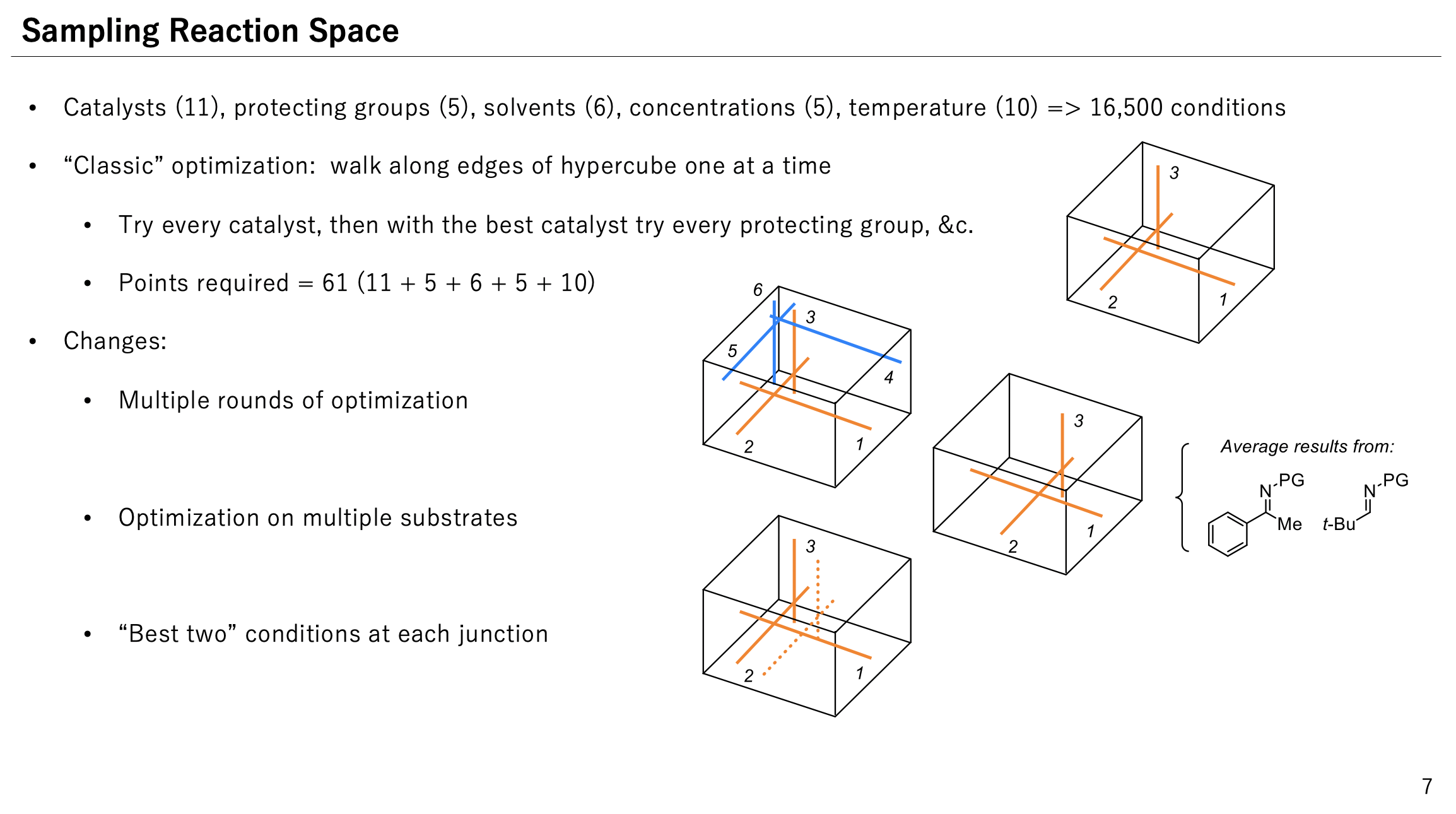

After a few months of work, Eugene and I had settled on the idea of a “catalytic reaction atlas” (in analogy to the cancer genome atlas) where we would exhaustively investigate catalysts, conditions, substrates, etc. for a single asymmetric reaction and then (virtually) compare different optimization methods to see which algorithms led to the best hits. Even with fairly conservative assumptions, we estimated that this would take on the order of 105 reactions, or about a year of continuous HPLC time, meaning that some sort of analytical advance was needed.

When I proposed this project to Eric, he was interested but suggested we focus more narrowly on the question of generality, or how to discover reactions with broad substrate scope. In an excited phone call, Eugene and I had the insight that we could screen lots of substrates at once by using mass spectrometry, thus bypassing our analytical bottleneck and enabling us to access the “big data” regime without needing vast resources to do so.1

Getting the analytical technology to work took about two years of troubleshooting. We were lucky to be joined by Spencer, an incredible analytical chemist and SFC guru, and eventually were able to get reproducible and accurate data by a combination of experimental insights (running samples at high dilution) and computational tweaks (better peak models and fitting algorithms). To make sure that the method was working properly, we ran validation experiments both on a bunch of scalemic samples and on a varied set of complex pharmaceutical racemates.

Choosing the proper reaction took a bit of thought, but once we settled on a set of substrates and catalysts the actual experiments were a breeze. Almost all the screening for this project was done in November–December 2021: in only a few hours, I could easily run and analyze hundreds of reactions per week.

I want to conclude by sharing three high-level conclusions that I’ve taken away from working on this project; for the precise scientific conclusions of this study, you can read the paper itself.

There are a ton of potential catalysts waiting to be discovered, and it seems likely that almost any hit can be optimized to 90% ee by sufficient graduate-student hours. Indeed, one of the reasons we selected the Pictet–Spengler reaction was the diversity of different catalyst structures capable of giving high enantioselectivity. But just because you can get 90% ee from a given catalyst family doesn’t mean you should: it might be terrible for other substrates, or a different class of catalysts might be much easier to optimize or much more reactive.

Understanding how many catalysts are out there to be discovered should make us think more carefully about which hits we pursue, since our time is too valuable to waste performing needless catalyst optimizations. In this study, we showed that screening only one substrate can be misleading when the goal is substrate generality, but one might prefer to screen for other factors: low catalyst loading, tolerance of air or water, or recyclability all come to mind. In all cases, including these considerations in initial screens means that the hits generated are more likely to be relevant to the final goal. Just looking for 90% ee is almost certainly not the best way to find a good reaction.

Although assay development is a normal part of many scientific fields, many organic chemists seem to barely consider analytical chemistry in their research. Any ingenuity is applied to developing new catalysts, while the analytical method remains essentially a constant factor in the background. This is true even in cases where the analytical workflow represents a large fraction of the project (e.g. having to remove toluene before NMR for every screen).

This shouldn’t be the case! Spending time towards the beginning of a project to develop a nice assay is an investment that can yield big returns: this can be as simple as making a GC calibration curve to determine yield from crude reaction mixtures, or as complex as what we undertook here. Time is too valuable to waste running endless columns.

More broadly, it seems like analytical advances (e.g. NMR and HPLC) have had a much bigger impact on the field than any individual chemical discoveries. Following this trend forward in time would imply that we should be making bigger investments in new analytical technologies now, to increase scientist productivity in the future.

A key part of this project (mentioned only briefly in the paper) was developing our own peak-fitting software that allowed us to reliably fit overlapped peaks. This was computationally quite simple and relied almost entirely on existing libraries (e.g. scipy and lmfit), but took a certain amount of comfort with signal processing / data science.2 We later ended up moving our software pipeline out of unwieldy Jupyter notebooks and into a little Streamlit web app that Eugene wrote, which allowed us to quickly and easily get ee values from larger screens.

Neither of these two advances required significant coding skill; rather, just being able to apply some computer science techniques to our chemistry problem unlocked new scientific opportunities and massive time savings (a la Pareto principle). Moving forward, I expect that programming will become a more and more central tool in scientific research, much like Excel is today. Being fluent in both chemistry and CS is currently a rare and valuable combination, and will only grow in importance in the coming decades.

Thanks to Eugene Kwan for reading a draft of this post.