One common misconception in mechanistic organic chemistry is that reactions are accelerated by speeding up the rate-determining step. This mistaken belief can lead to an almost monomaniacal focus on determining the nature of the rate-determining step. In fact, it's more correct to think of reactions in terms of the rate-determining span: the difference between the resting state and the highest-energy transition state. (I thank Eugene Kwan's notes for introducing me to this idea.)

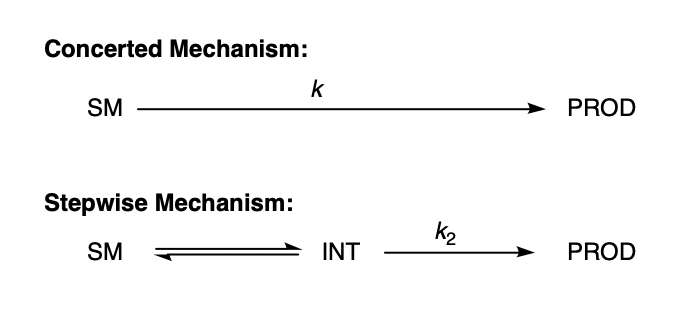

In this post, I hope to demonstrate the veracity of this concept by showing that, under certain idealized assumptions, the existence of a low-energy intermediate has no effect on rate. Consider the following system:

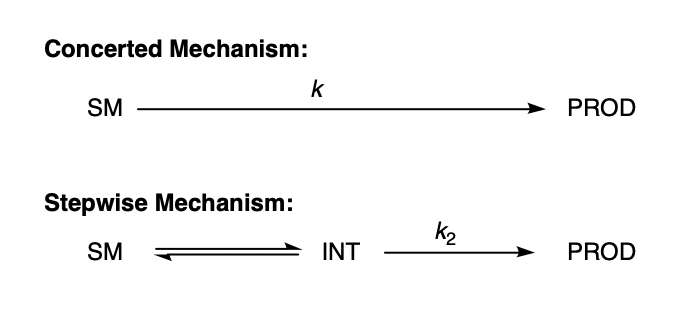

We can imagine plotting these two mechanisms on a potential energy surface:

In this example, X = Y + Z; the energy of the transition state and ground state are the same in both cases, and only the presence (or absence) of an intermediate differentiates the two potential energy surfaces. We will now compute the rate of product formation in both cases. Using the Eyring–Polyani equation, it's straightforward to arrive at an overall rate for the concerted reaction as a function of the barrier:

k = kBT/h * exp(-X/RT)

rateconcerted = k * [SM]

rateconcerted = kBT/h * exp(-X/RT) * [SM]

The stepwise case is only slightly more complicated. Assuming that the barrier to formation of the intermediate is much lower than the barrier to formation of the product, and that the intermediate is substantially lower in energy than the rate-limiting transition state, we can apply the pre-equilibrium approximation:

ratestepwise = k2 * [INT]

k2 = kBT/h * exp(-Z/RT)

ratestepwise = kBT/h * exp(-Z/RT) * [INT]

Solving for [INT] is straightforward, and we can plug the result in to get our final answer:

Y = -RT * ln([INT]/[SM])

[INT] = exp(-Y/RT)*[SM]

ratestepwise = kBT/h * exp(-Z/RT) * exp(-Y/RT) * [SM]

ratestepwise = kBT/h * exp(-X/RT) * [SM] = rateconcerted

As promised, the rates are the same—where the preequilibrium approximation holds, the existence of an intermediate has no impact on rate. All that matters is the relative energy of the transition state and the ground state.

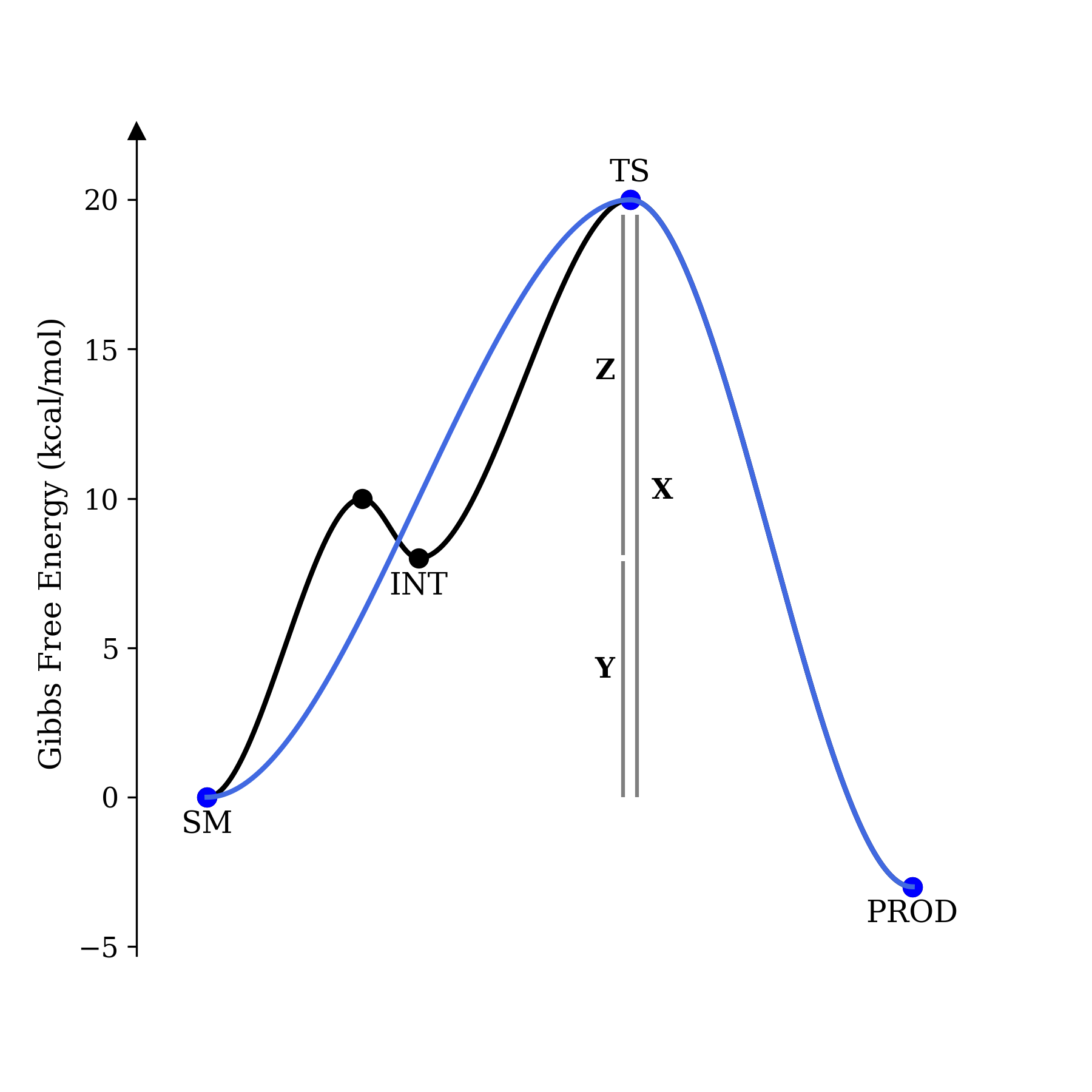

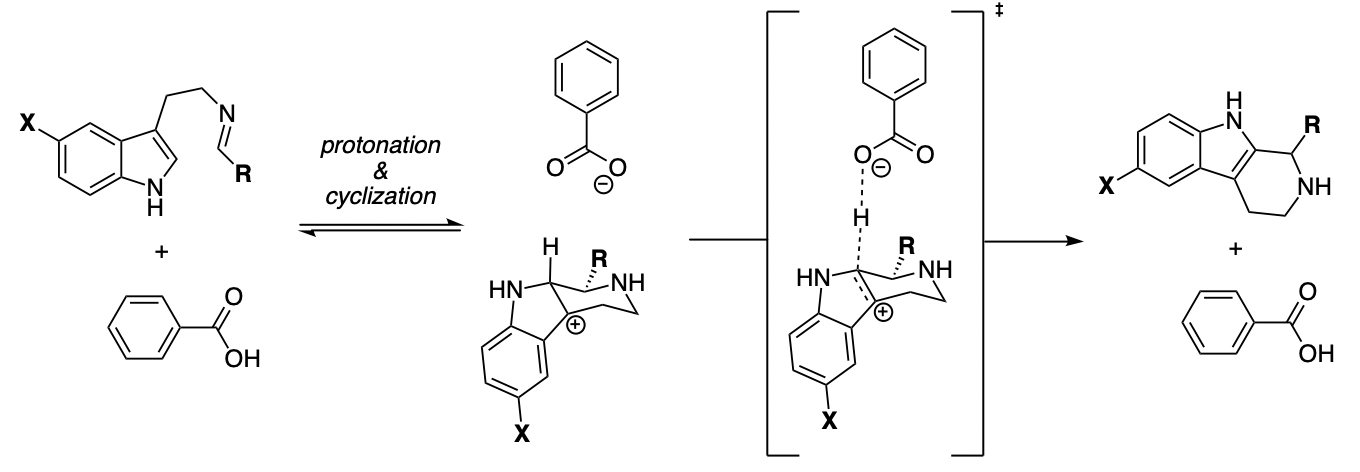

This method of thinking is particularly useful for rationalizing tricky Hammett trends. For instance, it's known that electron-rich indoles react much faster in Brønsted-acid-catalyzed Pictet–Spengler reactions, even though these reactions proceed through rate-determining elimination from a carbocation. Since electron-poor carbocations are more acidic, simple analysis of the rate-determining step predicts the opposite trend.

However, if we ignore the intermediate, it's clear that the transition state contains much more carbocationic character than the ground state, and so electron-donating groups will stabilize the transition state relative to the ground state and thereby accelerate the reaction. Thinking about intermediates is a great way to get confused; to understand trends in reactivity, all you need to consider is the transition state and the ground state.