This thesis, from Christian Sailer at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, is one of the most exciting studies I’ve read this year.

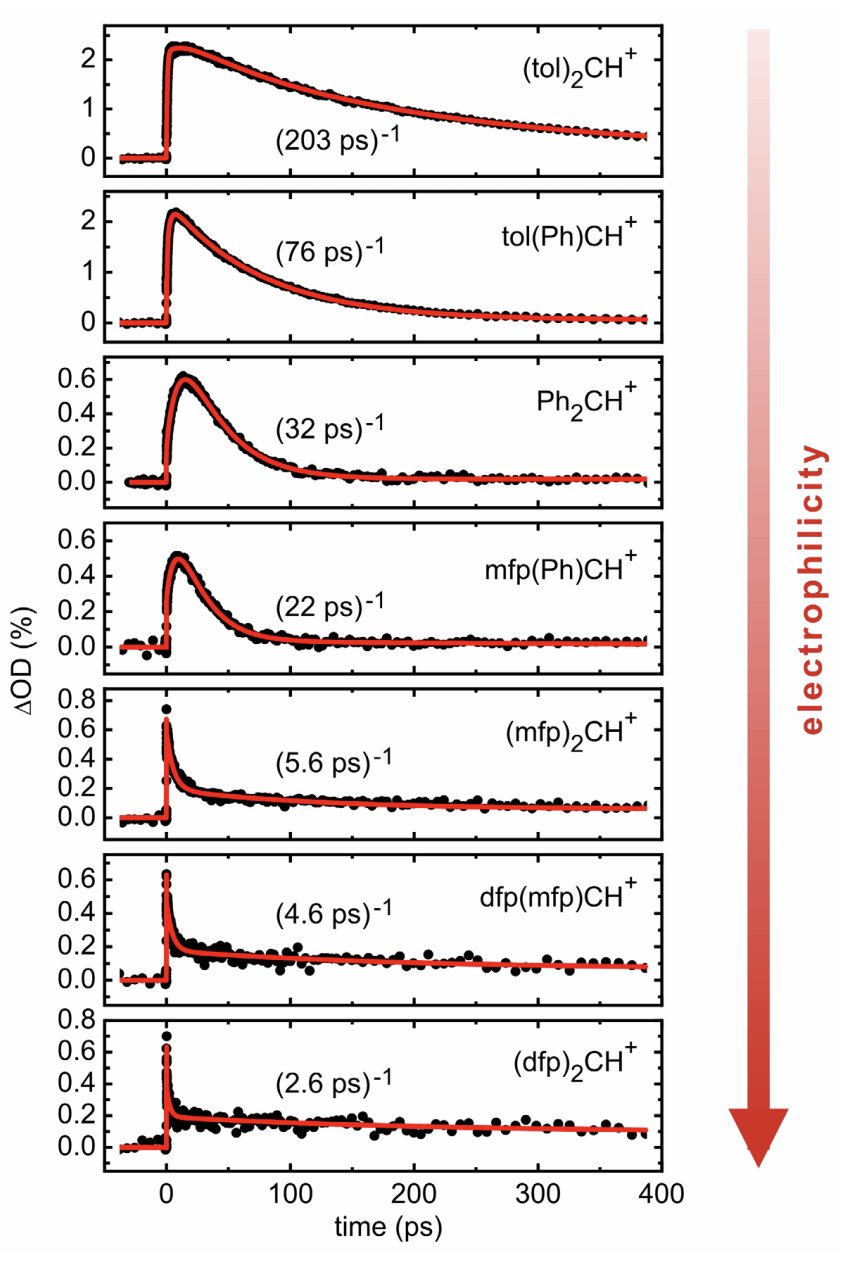

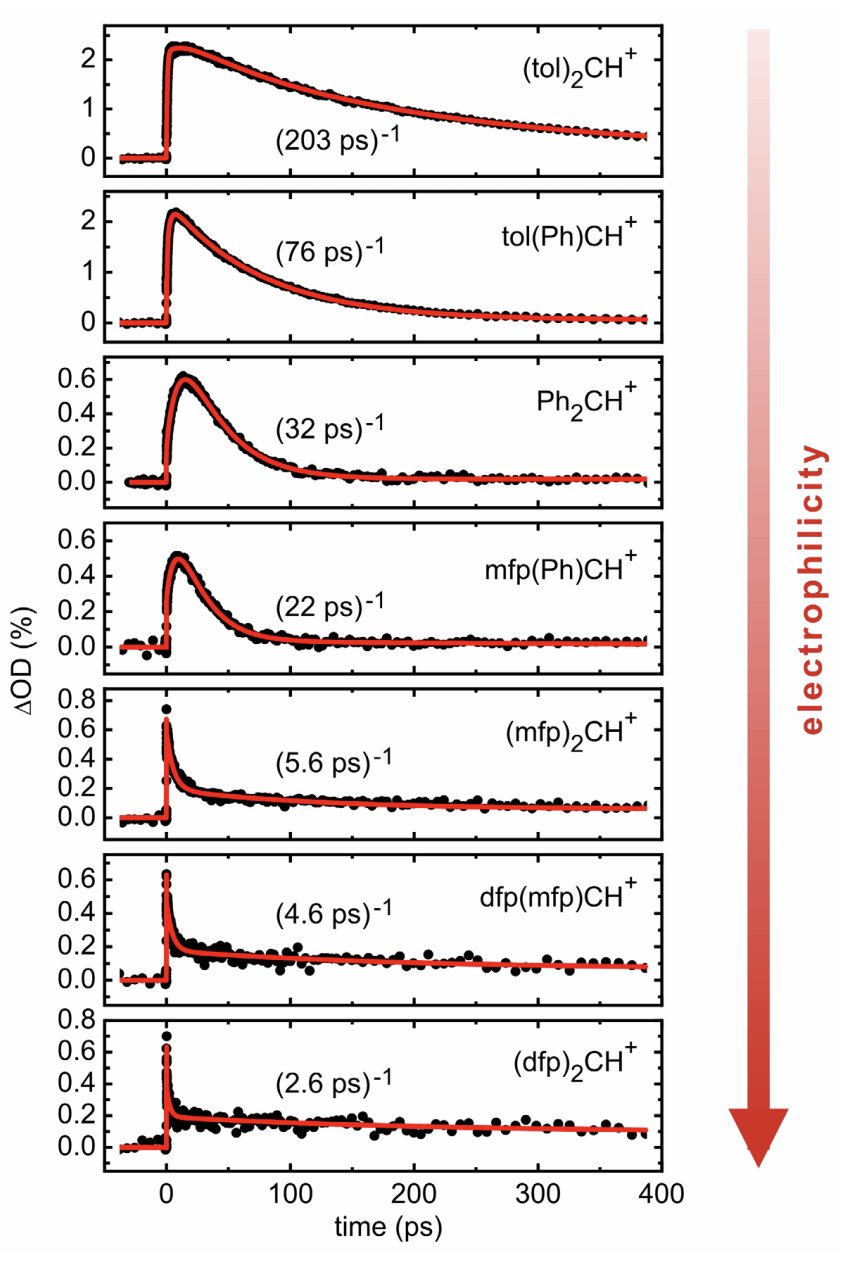

Sailer and coworkers are able to generate benzhydryl carbocations from photolysis of the corresponding phosphonium salts, and can monitor their formation and lifetime via femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy. (There are some technical challenges which I’ll omit here.) They then use this platform to study the addition of alcohols to these cations and obtain nice kinetic data on some shockingly fast reactions:

Although these species are extremely reactive, substituent effects are still paramount: adding two methyl groups to stabilize the benzhydryl carbocation extends its lifetime by 6.3x, whereas adding two electron-withdrawing fluorines shortens its lifetime by 5.6x. The most electrophilic species studied, (dfp)2CH+, reacts with methanol in only 2.6 ps! These findings demonstrate how even an extremely reactive carbocation like Ph2CH+ doesn’t react at the rate of diffusion with nucleophiles; although this reaction is almost instant on an absolute scale, there are still tens or hundreds of unproductive alcohol–carbocation interactions before product is finally formed.

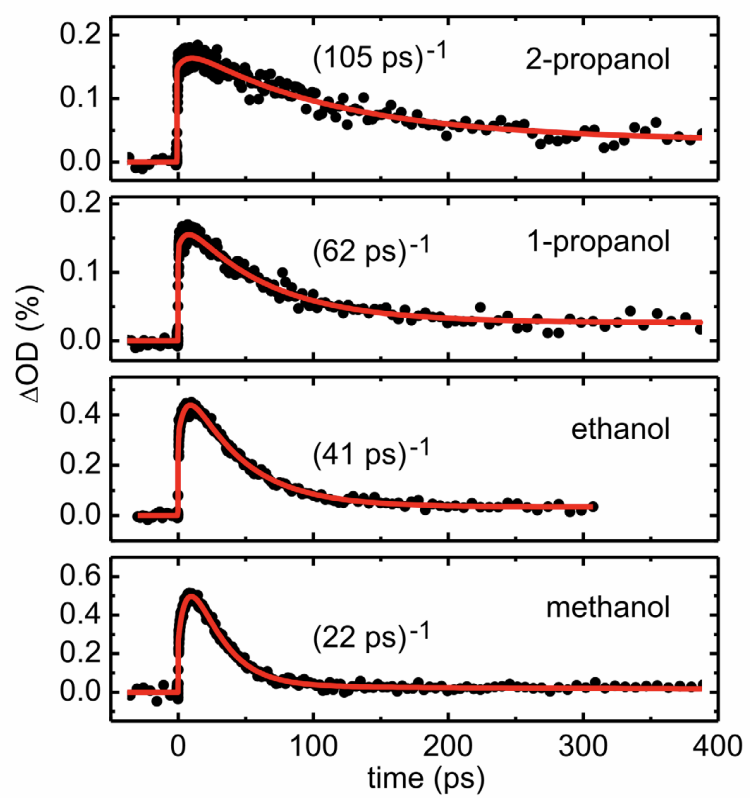

In contrast to Sailer’s results on the electrophile, which align nicely with results from more conventional kinetic measurements, different alcohols behave very differently:

This rate difference is surprising, since Mayr’s measurements demonstrate that there’s no conventional difference in nucleophilicity between these species—and intuitively, one wouldn’t expect adding additional carbons to substantially hinder approach to the oxygen. However, as Sailer notes, larger molecules rotate and reorient much more slowly than smaller molecules. This is evident from a number of different physical properties: larger alcohols form more viscous liquids and have slower dielectric relaxation times (how long it takes them to reorient in response to a new charge).

| alcohol | viscosity (ref) | dielectric relaxation time (ref) | reaction time (above) |

|---|---|---|---|

| methanol | 0.54 cP | 5.0 ps | 22 ps |

| ethanol | 1.08 cP | 16 ps | 41 ps |

| n-propanol | 1.95 cP | 26 ps | 62 ps |

| iso-propanol | 2.07 cP | 106 ps |

Sailer thus concludes that, as the timescale of reaction approaches the timescale of molecular motion, nucleophile reorientation becomes rate-limiting. This is a really cool conclusion, and highlights how the environment that reacting molecules “see” differs from our macroscopic chemical intuition: although we think of reorientation as barrierless, for very fast reactions reorientation is actually slower than bond formation. (Philosophically related, in my mind, is Dan Singleton’s work on non-instantaneous solvent relaxation, and how this influences the stability of reactive intermediates.)

Thus, this work simultaneously highlights both similarities and differences between ultrafast reactions and their benchtop congeners. My hope is that future studies can find ways to move beyond just benzhydryl cations and study elementary questions of selectivity with different nucleophiles (e.g. addition/elimination). The ability to observe what is typically the “invisible” step in SN1 is incredibly powerful, and I think we’ve barely scratched the surface with what we can learn from measurements like these.